Visual strategies for sound: the key to graphic scores

November 2021

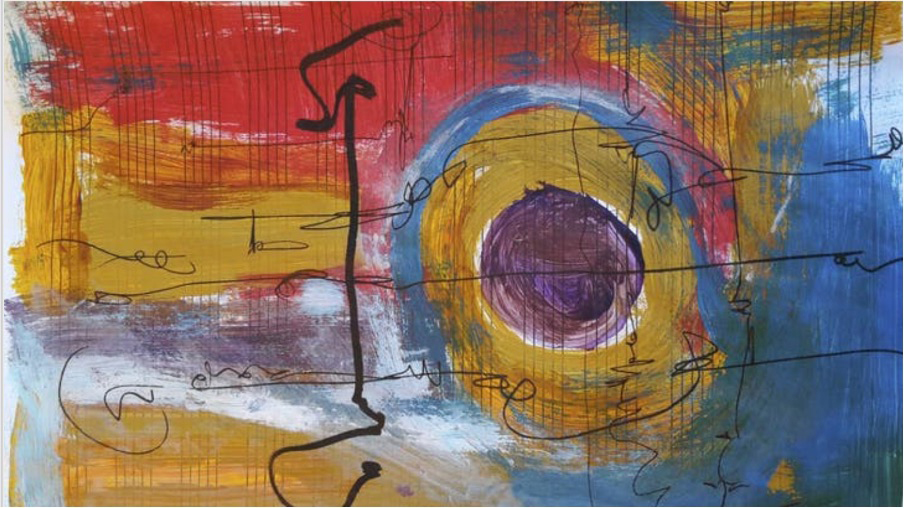

Renee Baker, Altered Consciousness 2 (detail)

Ahead of this month’s GIOfest, Una MacGlone of Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra identifies five key factors in creating graphic scores for large groups of improvisors

As a member of Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra for nearly 20 years, I have been fascinated by the diversity of approaches to making graphic scores for large improvising ensembles. Over the years GIO has commissioned graphic scores from George Lewis (Artificial Life, 2007) and Barry Guy (Schweben – Ay, But Can Ye?, 2008). Fred Frith, Satoko Fuji, Gino Robair and Anne Pajunen are among many other guests who have brought their own graphic scores to perform with us.

Alongside our work with guests, we encourage individuals in the band to explore and develop their own ways of creating visual strategies for a large improvising ensemble. This is in parallel to our continued mission to play freely, with no prearranged rules. The first night of this month’s GIOfest XIV is a collaboration with the Gaelic arts organisation Ceòl ‘s Craic. The featured soloists – singers Debbie Armour and Alasdair Whyte, Brazilian saxophonist Alípio C Neto, and Glasgow poet laureate Niall O’Gallacher – will bring song, poetry, spoken word, photographs and Gaelic place names, which I will incorporate into graphic scores for the Orchestra to perform.

Here I describe my process of creating graphic scores, and outline key aspects which influence my approach, as well as discussing examples of other graphic scores that I have played as a double bassist.

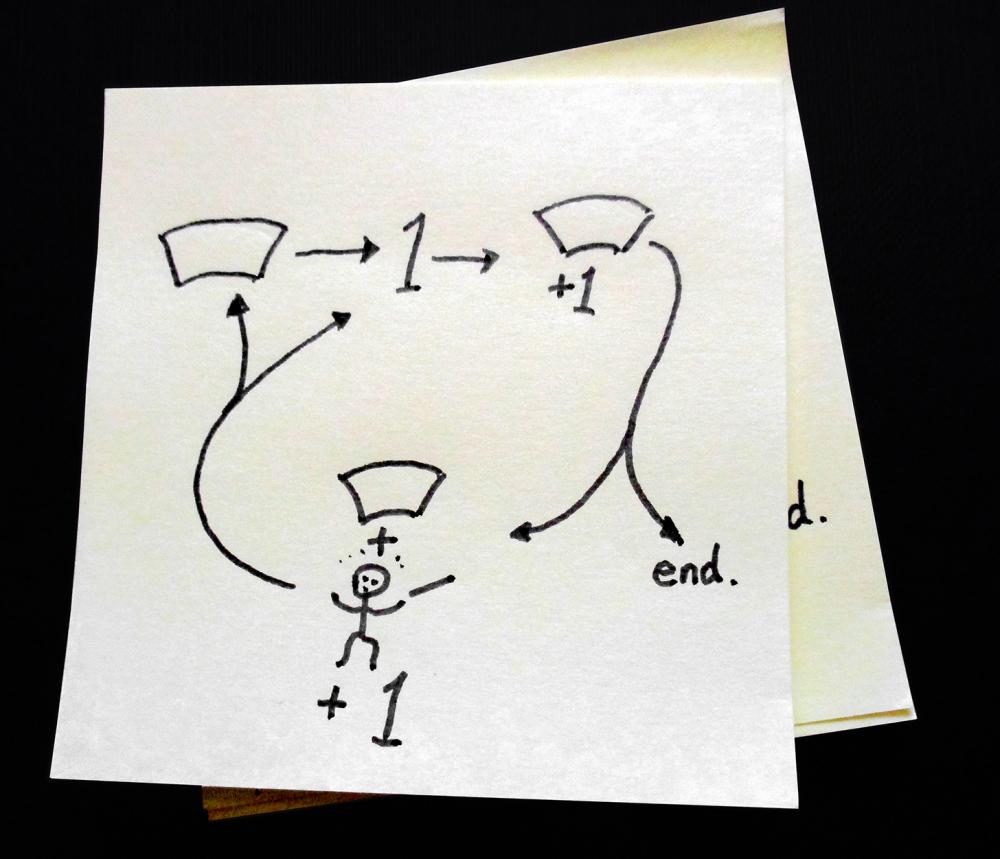

Jean McEwan, instant graphic score pack

Since 2016 I’ve used instant graphic scores packets created for me by artist Jean McEwan. These packets contain combinations of materials, for example, paper, tissue, images cut from magazines, plastic, painted card, sections of text. They are given to groups who arrange the elements to create a score and collaboratively decide how they will interpret it. There is, of course, always a third option – to let the elements fall where they may and to negotiate playing decisions in real time.

An instant graphic score, laid out on the floor, created by workshop participants, Glasgow, April 2018

Working with instant graphic scores has led me to appreciate how they can simultaneously hold many elements. This is particularly suitable for the GIOfest XIV collaboration which will include text, visual and melodic material. In my process of thinking about how to combine these, the importance of negotiating the following factors emerged: form; energy; materiality; clarity; and fixed material.

Form

Form is my first consideration and through this finding a balance between flexibility, so musicians have creative agency, and structure, so they know where they are in a piece. A graphic score that I have tucked away in a notebook is George Burt’s Improcherto (For HB), a piece designed to fit on to a post-it note. (HB is Harry Beckett; a recording with soloists Lol Coxhill and Evan Parker is available on the Iorram label.)

George Burt, Improcherto (For HB)

The score begins with a collective group improvisation denoted by the symbol in the top left hand corner. This is followed by an unaccompanied solo, denoted by the figure 1; after a while, the group joins the soloist. The piece can then move to an end or a conductor may step in to shape the group’s improvisation. After this part, the conductor steps down and either the group begins improvising or a new soloist steps up and the cycle begins again. In performance notes, Burt emphasises that decisions about moving from section to section should be negotiated collectively. Another important aspect is that the group can choose to follow or not follow the conductor based on their assessment of whether the conductor improves the music being made! For me, this piece presents a clear form yet allows the group to make decisions.

Energy

Thinking about conveying energy and atmosphere in scores leads me straight to a multidisciplinary, cross-genre artist from the AACM. I met Renee Baker in Chicago in 2009 and played with her groups in a variety of venues from the Velvet Lounge to a school gym hall. She brings a distinctive flair and energy to her projects, creating settings where performers can push their technique and artistry. A good example of this is her score Altered Consciousness 2.

A page from Renee Baker’s Altered Consciousness 2, a 24 page painted score for chamber ensemble

Baker’s work is simultaneously art and musical score, hung in galleries and read by musicians from the wall. She describes this work as ‘emotionally charged’ and informed by the aim to create a score that performers can respond to intuitively. Her practice as a composer of graphic scores has been informed by noticing how visual aspects are translated by performers into emotion, dynamics, texture, ranges of sound qualities, as well as harmonic and melodic material. This process of building up a knowledge of how people can respond to visual material and recognising the role of emotion in both interpreting and playing graphic scores is a shared aspect in both of our approaches.

Materiality

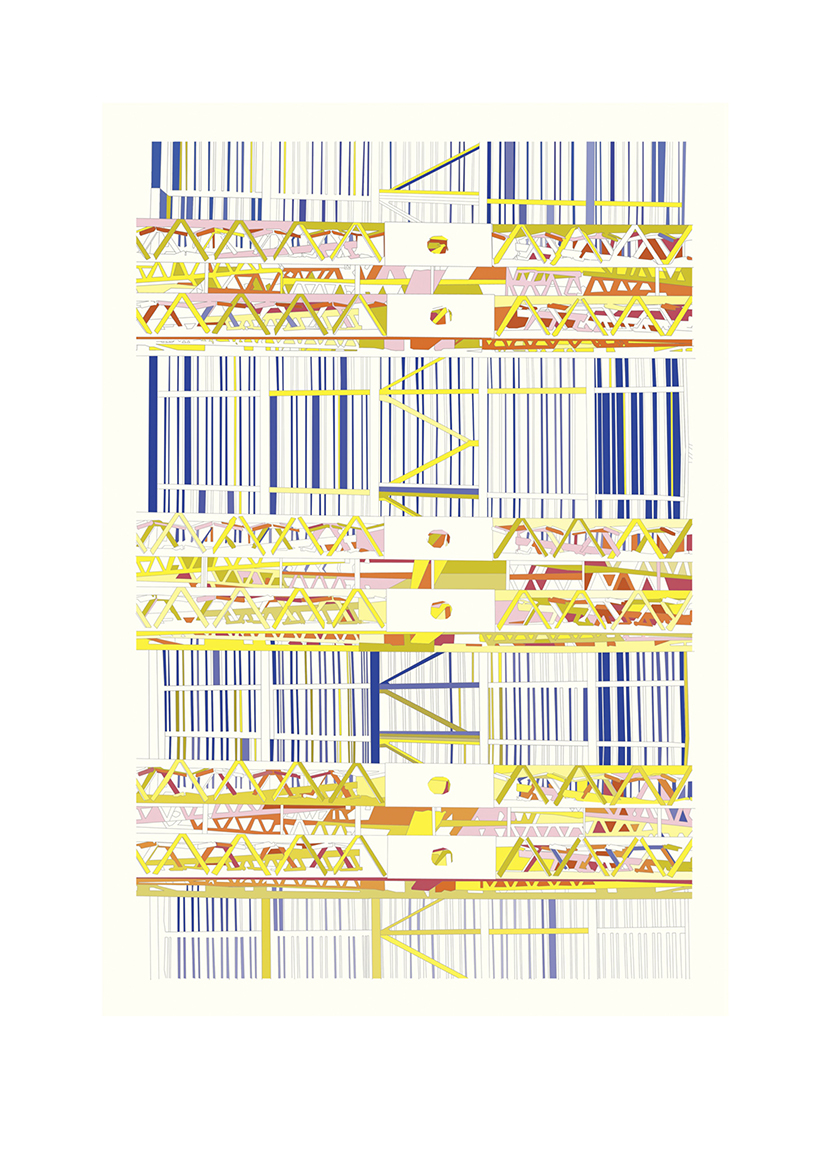

The quality of a score, how I perceive the dimensions and tactile-ness of the imagery, has a powerful effect on how I interpret and play it. This example below is from a collaboration by a visual artist (Jo Ganter) and an improvising musician (GIO saxophonist Raymond MacDonald). Their work has the goal for both to immerse themselves in the other’s discipline and take equal responsibility for images and direction of the resulting music. As with Baker’s work, their collaboration has been both performed and exhibited in art galleries.

Jo Ganter & Raymond MacDonald, Running Under Bridges

When performing this score, I feel drawn into the detail in the underside of the bridge and I picture my bass becoming a part of a massive sounding structure. This allows me to experiment with my musical role and material. When freely improvising, even though material is spontaneously created, I can sometimes find myself in old habits, where the music I play has a grounding, stabilising function. This score facilitated exploration of metallic sounds through preparing my bass with metal rulers and chopsticks and the mental imagery to occupy a different musical role.

Clarity

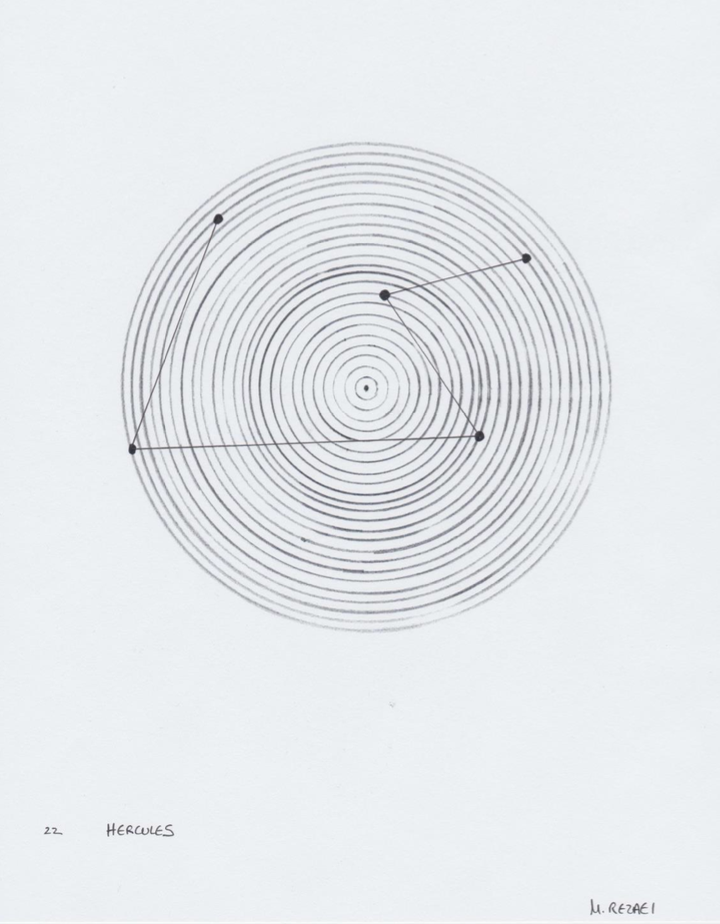

An intriguing challenge for me is to create clarity, particularly when an overarching aim is to offer choice and creativity to musicians. In her 2015 graphic score ANX, for GIO and The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Mariam Rezai skillfully creates space and intensity through a clear narrative. Each player has their own pitch diagram. This is my part:

Una MacGlone’s part from Mariam Rezai’s ANX

Players are grouped into different constellations, depicting ancient mythological characters. Each group has bespoke dynamics and operates as an independent organism within the larger whole. ANX is an immersive experience where sound slowly pulses around a large space. As a player it feels like being inside the middle of dynamic shifting universe. The score creates subtle shifts and relationships; the precision and delicacy in this process is demanding to achieve over a sustained time when improvising freely. These outcomes are of particular interest to me as an important theme in the forthcoming GIOfest collaboration is depicting a distinct and nuanced sense of different Glasgow places and their associated myths.

Fixed material

Another key challenge is integrating and negotiating fixed material, both melodic and rhythmic. Corey Mwamba’s score was performed by GIO in 2014 as part of the Commonwealth games and shows an innovative approach to offering performers expressive possibilities around and with fixed pitched material.

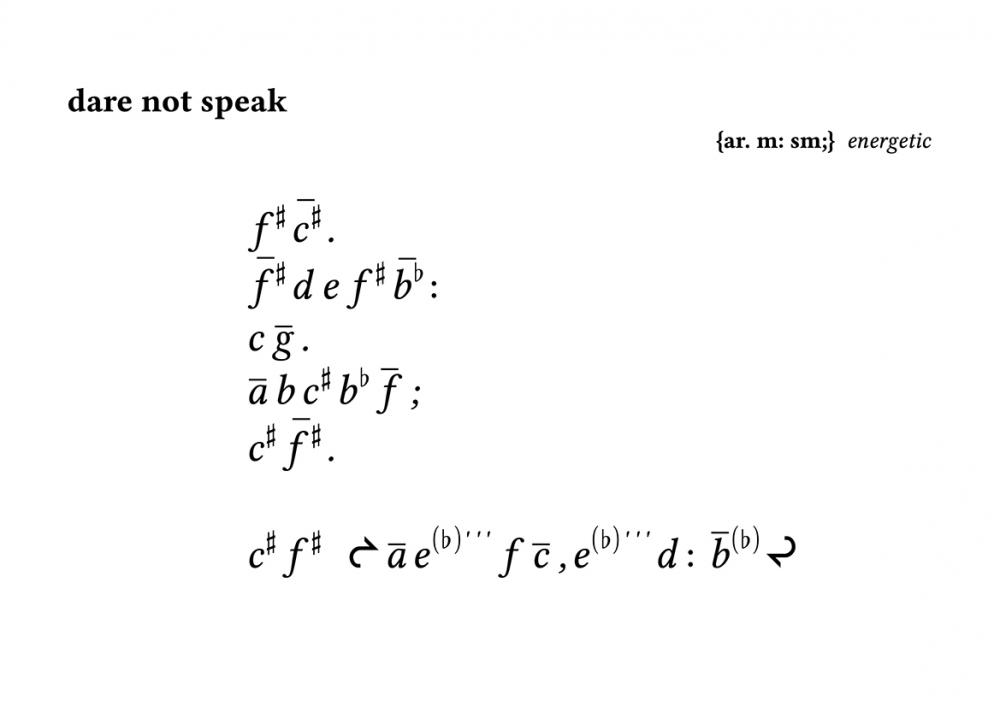

Corey Mwamba, Dare Not Speak

The punctuation symbols function to suggest rhythm and the accent marks denote melodic contour. Material within the ᖠ…ᖢ symbols forms a cycle. Performers have a choice how they articulate, express and move between notes within the parameters. The layout of the graphic notation is designed to aid memorisation, taking the music off the page and into the imaginations of the performers. In my experience, I found that when I had internalised the score, I could listen in more detail to others and also hear more playing options for myself. The later aspect is what I understand as the process of creative audiation in other words, imagining multiple musical options that may be played or not. For me, this process forms my experience of ‘flow’ when improvising.

At this point in my preparations for the opening night of the GIOfest, the elements of the collaboration are spread over floors, Google drives and emails. Before drawing these together, considering others’ graphic scores has allowed me to immerse myself in remembering their innovative and diverse strategies for musical creativity. I have presented my key concerns for creating graphic scores thematically as: form; energy; materiality; clarity; and fixed material. However, these are inextricably interlinked, one affects another. Performers can have their own visual, emotional, musical, sensory and aesthetic perception(s) of a score. They can create their own meaning and incorporate this into their interpretation. The possibilities for these diverse perceptions and interpretations is a key reason, for me, in why graphic scores offer exciting potential for both personal and group creativity.

GIOfest XIV takes place at Glasgow CCA between 25–27 November. Selected graphic scores performed at the festival will be published on the GIO website after the event. In 2022, as part of celebrations marking their twentieth anniversary, GIO will present a retrospective of their work with graphic scores.

Leave a comment