Clive Bell

Bell Labs: Requiem For Musical Instruments

May 2013

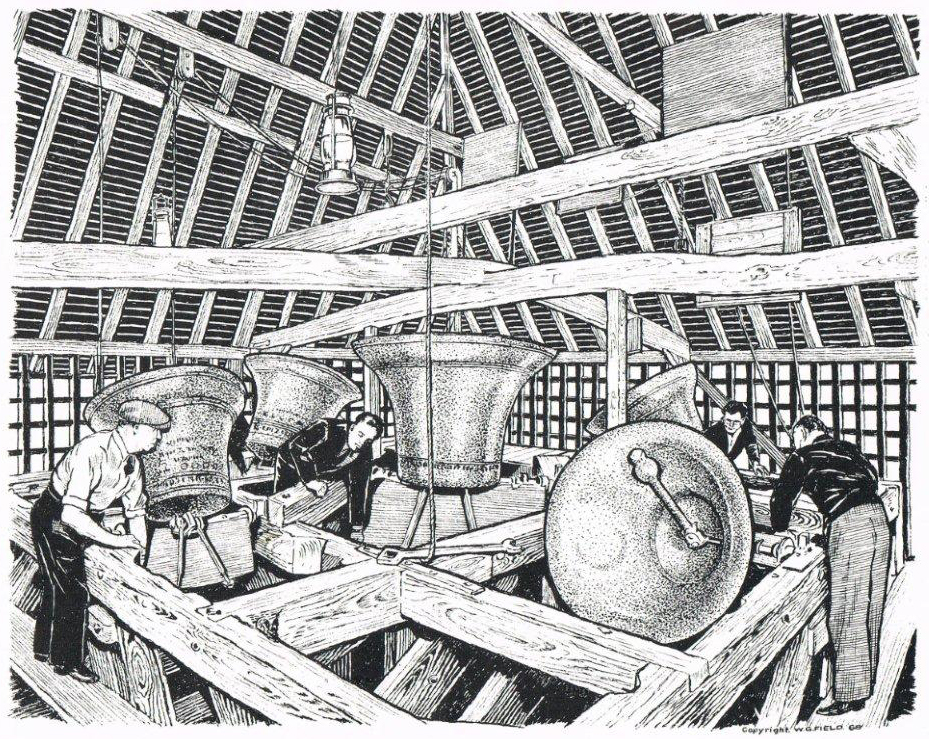

East Bergholt bell cage, by WG Field

In January 2013 Not Not Fun’s Britt Brown wrote an essay about the demise of the group as a musical phenomenon (Wire 347). Hawkwind, The Shangri-Las, Pere Ubu – it’s all over. This may have surprised those musicians busily organising band rehearsals across the country, but now I’m afraid the news has got worse. It looks like musical instruments themselves have had their day, and we are in an era when the electronic reigns supreme. Fun while they lasted: French horns, drums, contra-bassoons, church organs. You may even know someone who still plays an instrument, especially if you mix with teenagers. The truth is, a musical instrument is now something you dabble with on your way to mastering Ableton Live.

Brian Eno used to say he was not really a musician. By this he meant that he hadn’t undergone training to play a musical instrument. He doesn’t say it so much these days, because we are all Brian Eno now. Almost all music is electronic, or at least electronically manipulated, and all musicians are engaged in manipulation of electronics in some form. It’s particularly true of the underground, the music of Wire-world, where commercial considerations take a back seat to musicians’ desires. And what musicians desire is a new black box with knobs, a deck and a crate of vinyl.

I’ve been listening to Four Tet’s Rounds, reissued for its tenth anniversary. As Kieran Hebden scatters his Asian lutes and harps across hiphop beats, he resembles an evil genius in a Bond movie, cackling behind his gloved hand: “My crate-digging skills have ensured that every single instrument is at my disposal! Without ever taking a music lesson, I shall spend the next decade touring the world, spinning gamelan samples from my mighty laptop.”

Interviewing the Irish biwa player Charles Marshall, I learned that performing on this Japanese lute is not so much about entertaining an audience. The priority for a biwa student is your own spiritual development. As you progress in your control of the instrument, your spirit grows. Although many are unlikely to speak of it in quite those terms, this is a major reason why thousands of people still learn to play instruments. In the near future it may be the only reason left.

In case we needed more evidence, in March this year Harrods closed their instruments and pianos department. Many individuals have made the shift: Kaffe Matthews and Phil Durrant are more than ever engaged in Improv, but their violins have spent the last decade locked in their cases.

Amsterdam-based Hilary Jeffery is making wonderful records of apocalyptic drone with his group LYSN, but his trombone is reduced to occasional comment, while Jeffery focuses on his electronic devices, both self-built and purchased from Tom Bug’s Bugbrand. Bug is a good example of the self-taught backroom boffins enabling new music – he began by hand-etching analogue circuits and encasing them in cigar boxes, in a damp basement in Bristol.

Instruments still have their place, but it’s likely to be at the back of the class. On stage the quaint guitar or bass may still be present, fated (as Brown pointed out in his essay) to be fed through a Line 6 loop pedal and laptop. Then the proper music making can start. Alternatively, here’s a piece by Mark Fell, titled “Periodic Orbits Of A Dynamic System Related To A Knot.”

19 minutes into Fell’s exhilarating, hyper-synthetic frenzy, there appears an ethnic flute, of all things, for one minute of languid lyricism. It’s a Thai ‘pi saw’ flute, played by Jan Hendrickse. The original context for this free-reed flute is a gentle ensemble music in Chiang Mai, north Thailand:

Encountering such an instrument in Fell’s world is a fleeting, a trace memory of how music used to be made.

Meanwhile, like the proverbial policemen, electronic musicians are getting younger every year. Finnish schoolboy Eelis Mikael Salminen has released his first album aged seven: Suutre Teiter on the Fonal label. Using his father’s iPhone as a starting point, Eelis makes fresh, spontaneous dance music that is surprisingly advanced. By which I mean that, although Eelis has presumably never seen a dance floor, he sounds as though he’s already trying to break free from dance music’s prescriptions, to make underground music.

And it’s the 6-9 year olds that are targeted by the educationalists of the Furtherfield organisation, with their MaKey MaKey workshops.

All you need to bring is a laptop and an adult. In fact, this particular workshop is only partly about music – after a hectic morning you emerge with your own freshly created computer game – but Furtherfield, based in Finsbury Park, North London, also run hackdays to encourage development of electronic instruments. The aim here is to enable a wider range of music to be played by children with disabilities, that might bar them from playing cellos and lutes in the first place.

“There are only six widely available solutions for accessible music making,” says the Furtherfield website. “In contrast an orchestra is made up of at least 19 instrument types. This disparity needs to be bridged.” So the battle is on. But it seems to me to be already won, and those instrument types are waving 19 white flags of surrender.

Leave a comment