Philip Clark

Composers Anonymous: Where's London's New Music?

June 2013

Photo by Eva Vermandel

In his 1997 Lights Out For The Territory: Nine Excursions In The Secret History Of London, Iain Sinclair carves up the city by poet and writer. The suburban margins were JG Ballard’s; Michael Moorcock patrols Notting Hill; Angela Carter’s patch was Battersea to Brixton; Herne Hill belonged to Eric Mottram; Clerkenwell is synonymous with Peter Ackroyd; Stewart Home “commands the desert around the northern entrance of the Blackwell Tunnel” as Gerald Kersh “drinks in Fleet Street”. King’s Cross was there for the taking until 1995 when Aidan Dun published his epic poem Vale Royal and claimed the territory as his own. Which leaves Sinclair as the undisputed heavyweight Bard of Hackney – as Stewart Lee has said: “He thinks nothing there should be allowed to happen without his permission.”

The composer’s response to that list has to be to wonder "where is London’s New Music?", by which I don’t mean where in London you go to hear new orchestral, chamber and instrumental music, but where is the New Music that speaks of London? Where are those composers with ideas about the pace, wonder, frustration, scale, geography, vistas, romance, the self-serving politics, the ancient mythology; the city’s cultural strangulation-by-chain-store as the money-men hold the rest of us to ransom, willing us to forget that central London was once a more varied and characterful place.

There has to be a potential oboe concerto lurking somewhere in the sad truth that since Patisserie Valerie sold its soul and evolved into a chain, getting a decent cake in its original Soho establishment has become a near impossibility. Any composer wanting to write an opera buffa need look no further for a subject than the inexplicable rise and rise of an upper-crust blonde who levers himself into a position of power by playing the fool on mainstream television where upon, as he eyes the top job, everyone realises exactly what an opportunistic, right-wing bastard he is. And comedy turns to tragedy.

Writers have it easy. You just have to drop the words Charing Cross Road, St Paul’s Cathedral or Hampstead Heath into a sentence to invoke a deluge of memories and history; it’s likely even readers who have never set foot in the city will have a handle on such totemic places. Songwriters too have the advantage over composers. London pop – The Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset”, The Jam’s “Down In The Tube Station At Midnight”, London Calling by The Clash, “Primrose Hill” by John Martyn, “West End Girl” by the Pet Shop Boys, “Another Camden Afternoon” by The Stranglers, Ian Dury, Madness, Robyn Hitchcock’s latest album Love From London – has long tried to crack into the urban experience, the changing and volatile city, loves lost and found. Filmmakers (Alfred Hitchcock to Julien Temple), novelists (George Orwell to Will Self) have written themselves into the city narrative. But London composers – or to be more precise, composers who’ve based themselves in London – have chosen not to incorporate their environment into their work.

But this neat argument I’m constructing falls down when words, text and lyrics are taken out of the equation. What could be intrinsically Tufnell Park about your string trio? Or Boris about your lieder? Looking at the same argument from another perspective, we insist – although it’s become a lazy convention – on categorising the stylistic allegiance of music in New York City as uptown or downtown. Elliott Carter, who lived downtown in Greenwich Village, wrote works that were the very definition of uptown music. The minimalism meets Hendrix of the Bang On A Can festival was the downtown alternative – until they moved their annual marathon of performances uptown to Lincoln Centre. Downtown and uptown have long since stopped referring to geographical place; those words now signify an attitude, a way of doing.

Rolling Stone/New York Times journo Will Hermes’ excellent history of New York music during 1973–77, Love Goes To Buildings On Fire, pinpoints specific musical trends almost by grid co-ordinate. It's equally impossible to contemplate Feldman, Cage or Reich without New York City, as it’s impossible to imagine Boulez without Paris, or Terry Riley without San Francisco. But why hasn’t any British composer similarly managed to map onto manuscript paper the structures, the rhythms, the sonic blueprint of London?

Musicians gravitate to London with careerist intent, but composers invariably leave: Britten, Tippett, Birtwistle, Finnissy, Harvey, Ferneyhough, Dillon, Newman all made their careers outside London. 1950s composers interested in graphic notation and chance knew which New York loft would welcome them; Parisian composers who needed to immerse themselves in the aftermath of 12-tone music had a gleaming state-funded home to call their own. But London has always been "re" rather than "pro" active towards trends in composed music. No "isms" born here; no London-specific modern composition directions to offer to the world.

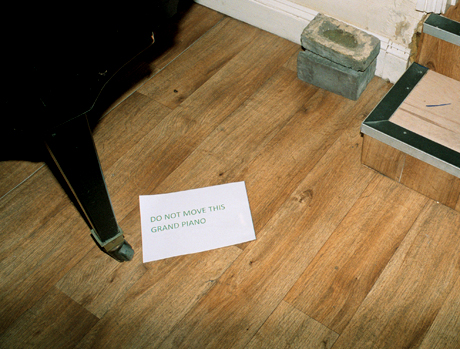

And, truth is, this is what London music still sounds like to most people:

But I’d like to suggest an alternative. In 1965, in a room at the Royal College of Art, the starting point of another way of conceiving music began to emerge. The musicians (who included Eddie Prévost, Cornelius Cardew and Keith Rowe, among others) had backgrounds in all points from Trad jazz to Stockhausen, which they managed to leave at the door as they constructed something new, something born out of their time, place and collective experience. Sounds like a genuine London music to me.

Comments

Hi, I wanted to let your networks know about A series of two hands on workshops for Composers, Writers and Artists that www.wavyline.org is running. I will be creating hands on exercises relevant to composers, that they will be able to complete alongside artists, writers and poets, thereby gaining more inspiration. See also Twitter: @wavyline02

www.wavyline.org

Leave a comment