A short guide to Julius Hemphill

March 2021

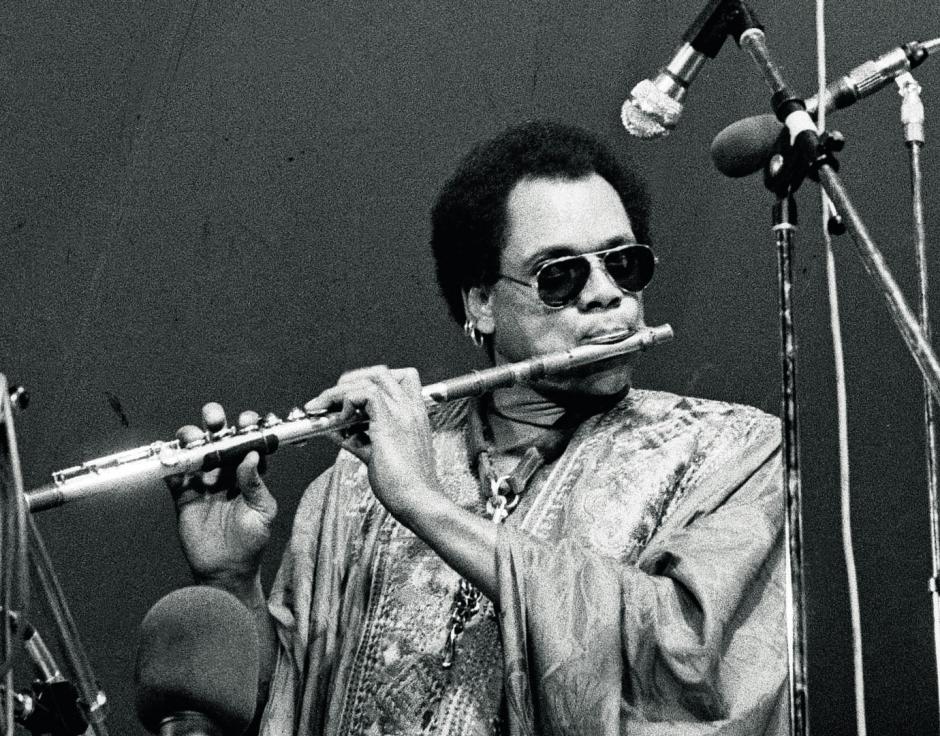

Julius Hemphill. Photo by Gérard Rouy

To mark the release of The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony Seymour Wright provides a tour of the composer and multi-reedist’s work

| Julius Hemphill “Dogon AD” | 0:14:49 |

| Julius Hemphill “Mirrors” | 0:07:08 |

| Julius Hemphill “Pensive” | 0:09:54 |

| Julius Hemphill “Part VII” | 0:12:10 |

| The Julius Hemphill Sextet “Mirrors” | 0:05:49 |

| Ursula Oppens “Parchment” | 0:07:01 |

| Julius Hemphill “In Periods Of Trance” | 0:02:31 |

| Julius Hemphill & Abdul Wadud “Slang” | 0:10:04 |

The work of saxophonist (mainly alto), flautist, vocalist, composer, conductor, arranger, organiser, bandleader, teacher and label founder Julius Hemphill (1938-1995) spans solo saxophone music, brilliantly poised small ‘jazz’ groups (often setting his alto with cello, drums and trumpet); compositions for chamber ensembles and big band; saxophone quartets, sextets and a saxophone opera; as well as collaborations with poets, dancers and fuller theatre works. At the heart of his unique body of work is a point of articulation, the join, between reflection and vigour, where the human voice – in words and speech, amplified and transformed by saxophones or flutes – feels ever-present.

I hear the ways, shapes and ensemble sounds of Hemphill’s lyric yet raw instrumental music looming large over much of the current ‘jazz’ landscape. “I think that music as we know it is autobiographical,” Hemphill wrote in the sleevenotes of his first solo record Blue Boyé (1976). And his practice feels particularly relevant today because of its focus on identity and history – how he organises, accommodates and encourages individual voices in collective, generous and inclusive ways. From musical structure, to his approach to the saxophone, his is an ideas-rich vision, full of potentials. It is forward looking and fresh, but situated within, and deeply reflective of, tradition and place. “You often hear people nowadays talking about the tradition, tradition, tradition. But they have tunnel vision on this tradition. Because tradition in African-American music is as wide as all outdoors,” Hemphill said in a 1994 interview. And his optimistic, political and mysterious celebration of this conception of tradition is an aspect of Hemphill’s practice I find compelling (and thought provoking).

Hemphill’s music sounds fantastic. Beautiful, often see-sawing, compositions draw together, and stack and balance, long meaningful lines that can flip from horizontal to vertical, from flat out to a full stop, and back. Solid, and often slow, rhythms work up and build open, multilayered spaces for solo dialogue and exchange. And crucially, the groups Hemphill assembled to play his music involve utterly distinct, and now definitive, instrumental voices – groups with, for example, cellist Abdul Wadud, drummers Phillip Wilson, Famoudou Don Moye and Warren Smith, and trumpeters Baikida Caroll and Olu Dara. Similarly, his later saxophone sextet music has been performed (and continued after his death) by a group of dedicated, virtuosic advocates, for example Marty Ehrlich, James Carter and Tim Berne.

Julius Hemphill

“Dogon AD”

From Dogon AD (Mbari, 1972)

Dogon AD was recorded in St Louis in February 1972. It was the second release on Hemphill’s own label – Mbari. It’s an ideal and logical way into his work. Hemphill grew up in Texas, toured with Ike and Tina Turner (work he described as boring) before moving to St Louis, where he was a key member of the Black Arts Group, and began to develop his interdisciplinary practice. Dogon AD features the quartet of Hemphill, cellist Abdul Wadud, drummer Philip Wilson and Bakida Caroll on trumpet. The title tune Dogon AD unfolds slowly, at length (like so many others in the Hemphill canon). “AD stands for adaptive dance, and I had in mind a dance all along,” Hemphill explained. And across the warp of (particularly pitch conscious drummer) Wilson’s solid slow cymbal count and tom-kick-kick-tom-tom beat permutations, Wadud bows an off-on horizonal cello weft. On this fabric Hemphill solos first, Caroll follows. Their parallel lines dance tendrils in rock steady celebration.

Julius Hemphill

“Mirrors”

From Raw Materials And Residuals (Black Saint, 1977)

By the mid-70s Hemphill had relocated to New York. Raw Materials And Residuals was recorded there in 1977 by a trio of Hemphill, Abdul Wadud and drummer Famoudou Don Moye. The striking cover photo of a shaven-headed Hemphill, arms folded across his naked torso with his alto saxophone hanging pendular, connotes something precise, poised and physical. The same goes for the elemental, alliterative poetics of its title(s). The LP’s five compositions present a svelte, sinewy, structured trio music that, as Hemphill puts it in his sleevenotes, “progresses from vigour-to-reflection-to-vigour”. It is an album of clarity and un-compromise. It is also a brilliant recording of Hemphill’s metal-hard saxophone sound – silver, guttural, in which the voice is ever present – Wadud’s cello and Don Moye’s percussion (outside the context of the Art Ensemble).

Julius Hemphill

“Pensive”

From Wildflowers: The New York Loft Jazz Sessions (Douglas/Casablanca, 1977)

Hemphill was an integral figure in the loft jazz scene of 70s New York. A sense of how the rich community of musicians Hemphill worked with in the 70s gave life to, overlapped in and inhabited his group music comes across through the one Hemphill track included on the five LP series Wildflowers: The New York Loft Jazz Sessions. Here, versions of the two groups above (less Caroll but plus guitarist Bern Nix) are folded together in a performance of “Pensive”, a composition that moves from ensemble shapes to solo passages. At once hard and delicate, it’s also an emphatic example of an intensity built from a slow pulse and space intrinsic to much of Hemphill’s work.

Julius Hemphill

“Part VII”

From Roi Boyé And The Gotham Minstrels: An Audio-Drama (Sackville, 1977)

Hemphill’s two solo LPs of the 70s are unique in using tape and multi-tracking of alto and soprano saxophones, flute and voice (and field recordings) to create complex, longform sonic environments – his 1977 Roi Boyé And The Gotham Minstrels is subtitled An Audio-Drama. Hemphill’s words and instrumental voices meld whisper, hum, bark and intone long, slow (polemic) reflection. His sleevenotes explain the “use of orchestrated language that proceeds from the rhythmic impulses of the spoken word and does not obey the dictates of metre nor of melody except for the expressive inflections associated with speech in generally colloquial situations.” Across Roi Boyé’s four sides unfold a reflection on Gotham (New York) that rewards repeated, patient listening. As the drama develops onto the final side the word patterns of Hemphill’s lyrics, and his improvised and multitracked alto, soprano and flute lines coalesce, melt (and reveal) the limits of meaning making in word and sound. It is a meticulous, resourceful visionary music.

The Julius Hemphill Sextet

“Mirrors”

From Five Chord Stud (Black Saint, 1994)

Hemphill’s version of saxophone polyphony is unlike anything else. As a saxophonist I find the prospect of massed saxophones excruciating. But not Hemphill’s. His sextet music sings and growls in rich, stern yet playful, celebration of the voice amplified by reed and metal cone: mega-saxophones (or long tongues, as his saxophone opera was titled).

From the late 70s to his death in 1995 Hemphill composed, performed and conducted quartet and sextet saxophone music. He was a founding member and main composer for the World Saxophone Quartet and recorded two two sextet albums for Black Saint – Fat Man And The Hard Blues (1991) and Five Chord Stud (1994). On the latter he does not blow a note – his playing was curtailed by ill health in the final years of his life. Instead he conducts an ensemble of technically consummate saxophonists through his new and old compositions. “Mirrors”, recorded first on Raw Materials And Residuals, receives a thoroughly polyphonic treatment as Hemphill conducts the tune out into an ensemble improvisation and back

In early 2021 New World Records release a seven CD box set of Hemphill’s hitherto unpublished music: Julius Hemphill (1938–1995): The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony. It offers a fresh view and much more insight into his oeuvre, making available for the first time much unreleased material of Hemphill’s many fascinating smaller ensembles. Much of it is live (in contrast to the majority of his recorded output is studio). There’s another, great longform quartet version of “Mirrors” with Caroll, Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. The set also makes available more recordings of his fully composed chamber music.

Ursula Oppens

“Parchment”

From The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony (New World, 2021)

The piano hardly features in Hemphill’s music. The harmony comes from cello, guitar, or choral, parallel horn lines. But he also composed music for solo piano, and piano with string quartet. It is intriguing to hear Hemphill’s music channelled through fingertips and keyboard. The solo piano composition “Parchment” was performed in 2007 by Ursula Oppens, a pianist completely understanding of Hemphill’s work.

Julius Hemphill

“In Periods Of Trance”

From The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony

Given how core to Hemphill’s work the voice is, it seems natural that the first LP to be released on Hemphill’s Mbari label in 1971 was in fact a record by poet Curtis K Lyle, The Collected Poem For Blind Lemon Jefferson. Hemphill plays behind, and around, Lyle’s reading of his longform poem. And they are joined on the final track of the B side by the third voice of Malinké Kenyatta. Hemphill worked elsewhere with both poets. The box set offers new (unpublished) unheard recordings of Hemphill with both. A duo performance with Lyle – “Unfiltered Dreams” from 1982 – includes a short recitation where Hemphill puts aside his saxophone altogether and speaks, amplified and with reverb, over Lyle’s vocal in-periods-of-trance rhythm.

Julius Hemphill & Abdul Wadud

“Slang”

From The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony

Perhaps the key association throughout Hemphill’s recorded music is that with the brilliant cellist Abdul Wadud. Their creative connection was particularly close, empathetic and emphatic – what Wadud called a unique musical relationship. No one sounds like either of them, and together they sound like nothing else. The tenor, spring and bend of Wadud’s (juicily amplified) plucked, strummed and bowed cello is perfectly balanced against the silver of Hemphill’s alto (and occasion soprano). Across a 25 year plus association they recorded two albums of remarkable, emphatic duo music – Live In New York (1976) and Oakland Duets (1992). One of the real treasures of this box set is another long duo concert of their music, recording date and location unknown.

Read Andy Hamilton's review of The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony: Archival Recordings 1977–2007 in The Wire 446. Subscribers can also read an interview with Hemphill in The Wire 49 from March 1988 via the digital archive. You can find out more about Seymour Wright's own music at his website.

Leave a comment