Read an extract from Black Mystery School Pianists And Other Writings

April 2025

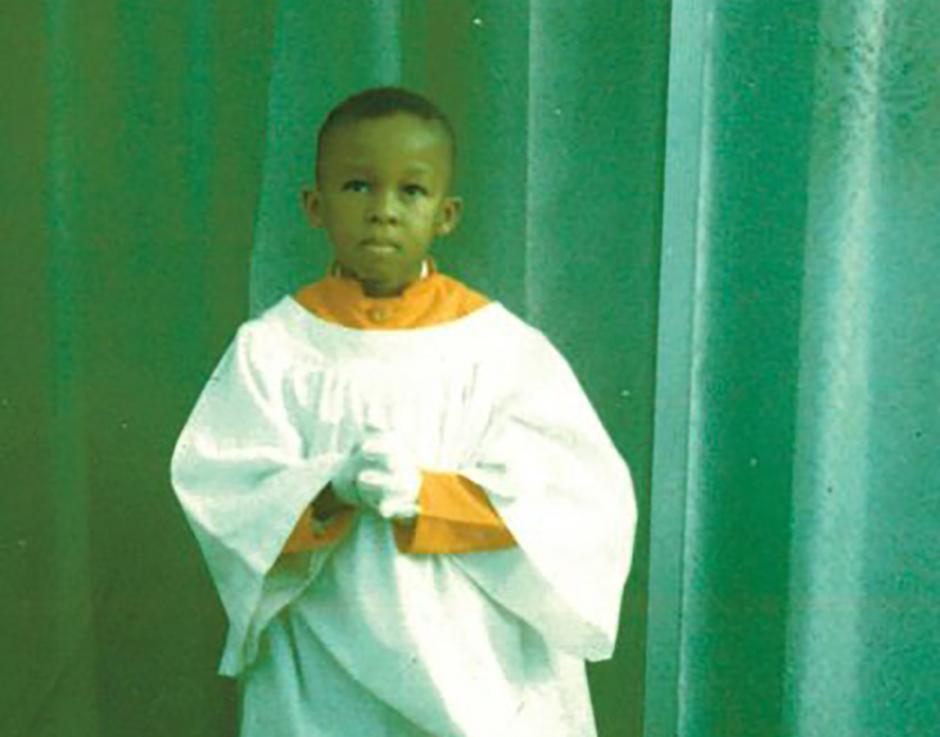

Matthew Shipp on the cover of Black Mystery School Pianists And Other Writings

In an extract from his new book, US pianist Matthew Shipp outlines what he means when he talks about Black Mystery School pianists

In viewing the history of jazz piano as it has influenced me, I find various tributaries and streams and ways of being that have contributed to my understanding of the jazz piano language and to finding my way through all of this. I have come to see a subgroup of jazz pianism that has influenced me as something I call the Black Mystery School of Pianists. Like all categories, there is an illusionary aspect of it and phenomena go in and out of each other, but the category does denote something. It’s a way I have viewed the work of certain practitioners of the art of jazz piano, and I have followed offshoots of this branch. There are many pianists that might fall in and out of this category that are not mentioned here. The list is an outline that defines aspects of a certain attitude and is not meant as any type of dogmatic statement.

So what do I mean by a Black Mystery School pianist? Well, obviously the word “Black” is in here, so for the purposes of looking at this tree, all of the practitioners I will mention except for one – will be Black. That is not to imply a non-Black person cannot enter this realm. I am just outlining a code – that there is a definitive tree-like formation that has seemed more often than not to go down a certain path.

The word mystery is here also, which implies a secret code, passed through an underground way of passage – a language outside the mainstream and, yes, outside the mainstream of jazz – even though the father of this school, Thelonious Monk, has had his image subsumed into the mainstream of jazz after a long period of incubation.

Mystery School posits an alternative touch – something that does not directly fall within the mainstream’s easily digestible paradigm of being able to play the instrument. Even though the practitioners of the Mystery School are obviously highly skilled virtuosos whose touch, language, and articulation are extremely hard to copy, they resist easy categorisation.

In some ways, in the subconscious of the jazz idiom, the Mystery School is a counterstrike to the psychological space of any variant of an Art Tatum approach to playing – filtered down to Oscar Peterson, and then watered down to something like André Previn – as a prevailing way of viewing piano playing. And I say that despite Monk’s roots in stride piano.

Mystery School pianists have developed profound ways of generating sound out of the instrument, grounded in a technique they invented – one that cannot be taught in school. It is a code that somehow gets passed down.

The Mystery School seems to have a subconscious urge to resist academic codification of any sort. Despite however great artists and jazz musicians they are – and this is not meant as a pejorative – jazz students can go to jazz schools and learn to play like Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett and Herbie Hancock. But there is something completely elusive in the sound world of Randy Weston, Mal Waldron, and the legendary Hasaan Ibn Ali that defies the jazz academy.

The other major aspect of the Mystery School is its iconoclastic nature. As in the ultimate example of Monk, the artist carves out a niche for themselves within the world of the jazz universe. That niche is a worldview – a planet. The artist in utmost stubbornness will stick to that vision with a fuck the world attitude – that the world will have to come to this vision of the piano and, if it doesn’t, then so be it. This vision is extreme in its iconoclastic nature, although some Mystery School pianists, like Mal Waldron, have done gigs like backing singers (eg Billie Holiday, etc).

The phrasing and rhythm employed in the code that these players utilise is of such nature as to not be able to fall under the hands of a jazz student who is studying, say, Brad Mehldau.

Another aspect of the Mystery School is that, despite Monk being the spiritual father, the descendants tend not to play Monk tunes. They develop their own body of work. And I say this despite some great interpretations of Monk music by Mal Waldron through the years.

Next, let’s look at who is not in the Mystery School, according to this very particular way of looking at things. This is important because this is such a specific delineation of a slice of something that it is not a platform to just throw a bunch of great jazz pianists in. It is very specific.

So first, Ellington is not in, although he is a big influence on the pianism of Monk, Randy Weston, and Cecil Taylor. Also, Ellington’s piano work on the album Money Jungle is on the level of the greatest piano playing ever. It is playing that could never be reached by someone with the mindset of a post-Tatum pianism, and no one who comes out of a bebop or post-bebop mindset could ever get to the language there. Hank Jones, Wynton Kelly, or Tommy Flanagan – as great as they all are – could never generate the energy/sound fields that the piano work on Money Jungle does.

So that is to say Ellington had a unique homemade style that is as idiosyncratic as any. But Ellington doesn’t fall into this school because there is a posture and an attitude inherent in the code that he does not quite embody, and his relationship to the mainstream of his day does not exactly delve into the stance and attitude of the Mystery School.

Bud Powell does not make it in the school because he is too tied to the classic idea of the development of bebop. That might seem a paradox being that Monk is also considered a founding father of bebop – but isn’t that one of the main things that gives juice to Monk’s legacy? That he is a founding father of bebop but at the same time set up a parallel universe of his own music that in some ways seems like it is counter to some of the assumptions of bebop?

There is that aspect of the Mystery School that sets itself up as counter to bebop. Of course, Bud Powell is one of the greatest pianists ever to sit at the keys. But that does not put him in this particular school, although Bud is transcendental.

I also do not include Mary Lou Williams. Bud and Monk used to go over to her place – she helped them both with touch on the piano. She usually did not go for the oblique, though. But she is a tremendous jazz pianist.

If you use the word “mystery”, and the math of the pyramids comes to mind, then you could not think of a more profound player than Horace Silver, because his playing is undergirded by a code of this sort. But he does not make the school because he is in a different headspace. I look at him as a super gifted post-Bud Powell player who developed his own unique style and attack within those parameters and then went on to help invent hard bop. But his stance doesn’t have the punk attitude that the Mystery School can have, and I don’t think he would have ever been comfortable with the idea of being an underground language.

Erroll Garner could never be in this school, though strangely enough his playing could be very idiosyncratic at times and is obviously homemade. But the areas of American culture that he was an actor in do not allow entry into this club. (I have an aunt who thought Erroll was the greatest pianist ever, but she went to her grave saying Monk could not play the piano.)

I have wrestled with whether Elmo Hope belongs in the group. I am not sure. I go back and forth for different reasons. If he is, a lot of it would be because of his influence on Hasaan Ibn Ali, who is another extreme of an ultimate example of this.

Most free jazz pianists do not make the list because the Mystery School is not about free jazz per se. And I say this despite the fact that most free jazz pianists feel a relationship with Monk, despite Monk’s problematic relationship with free jazz. But Cecil Taylor makes the list because he is a contemporary of Randy Weston and Mal Waldron, and it is fascinating to see those three artists as branches off the Ellington/Monk piano branch. You could not find three artists as different as these three masters, yet they get their nourishment from some of the same sources.

McCoy Tyner does not make the school, because the Coltrane universe is a cosmology in and of itself and must be dealt with that way apart from everything else. I say that despite the fact that McCoy was influenced by Hasaan Ibn Ali and used to go over to his house in Philadelphia and soak in things.

This is an extract from Matthew Shipp’s Black Mystery School Pianists And Other Writings which is published by Autonomedia.

You can read Stewart Smith’s review of the book in The Wire 495. Wire subscribers can also read the review online via the digital library.

Leave a comment