Read an extract from Semi-Conducting – Rambles Through The Post-Cagean Thicket

February 2025

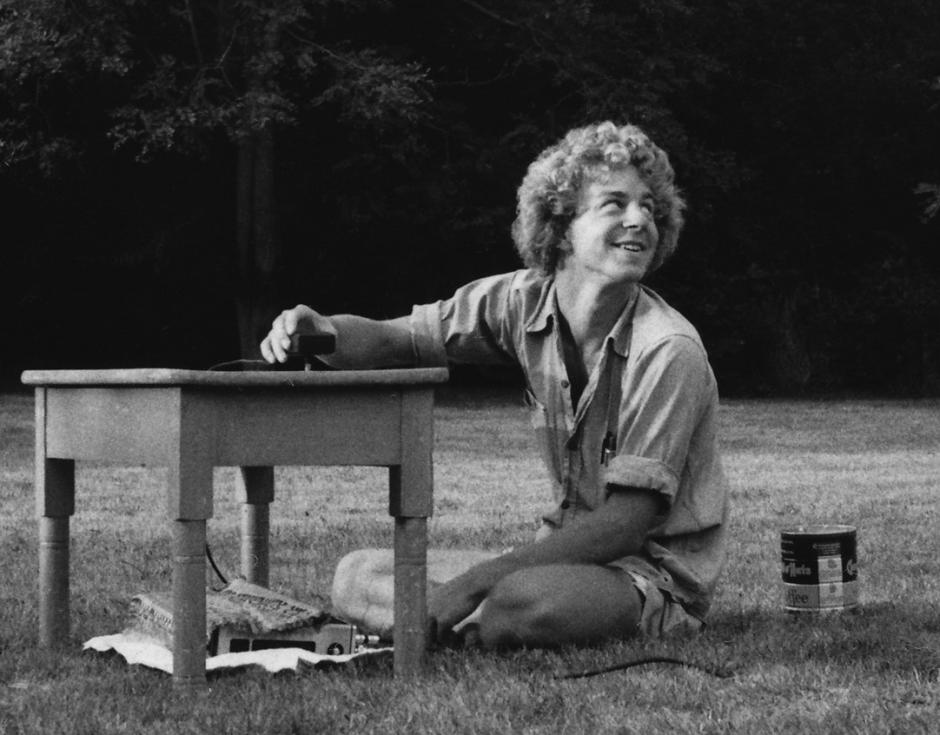

Nicolas Collins experimenting with contact microphone feedback, 1974. Photo by George Collins

Read an extract from Nicolas Collins’s Semi-Conducting – Rambles Through The Post-Cagean Thicket, in which the author describes his early experiments with feedback

From Chapter 6: “The Infinite Amplification of Silence (or I Ching for Dummies)”

By the end of my first year at Wesleyan University, I had fallen so fully under the spell of John Cage’s credo “any sound can be a musical sound” that I was creatively paralysed. If any sound could be a musical sound, why even make one? Surely, there were enough out there already. I spent hours in front of the ARP synthesizer but felt no compelling reason to select one configuration of patch cords over another, or to sequence my recorded material in any particular order. I yearned for a methodology, something that did not depend on my personal taste, an inherited tradition, or danceable beats. The composers I admired had invented individual solutions to this problem: Cage had the I Ching, Steve Reich had tape loops, and Alvin Lucier had a priori acoustic phenomena. Finally, feedback came to my rescue.

When I plugged a microphone into an amplifier and turned up the volume, feedback’s Zen-like infinite amplification of silence generated a haunting whistle with minimal interference on my part. It served as an electronic I Ching for dummies: I moved the mic instead of tossing yarrow sticks – notes emerged, but I never knew which pitch would pop out next. The results were guided by acoustics rather than by chance or choice. Lucier’s exploration of the behaviour of sound in space liberated me from my assumption that music had to be rooted in previous music. Acoustics became the glue to unify my disparate interests into a personal musical style. I became fascinated by the ways feedback could give voice to objects and spaces – trombones, tabletops, culverts, concert halls – with minimal composerly oversight.

Feedback happens when the output of a dynamic system is connected back to its input. ‘Negative’ feedback, in which the output is subtracted from the input, is the essential self-corrective property of various cybernetic and machine control systems. The shriek of a microphone in the hands of a novice politician or the roar of an electric guitar held up to an amplifier are examples of ‘positive’ feedback: the output of a speaker is picked up by a microphone and amplified sufficiently to add up and cascade on rather than fading away. The politician’s voice is drowned out by a loud pitch at whatever frequency the equipment can produce with the least energy. Positive feedback also occurs if you connect a patch cord from the output of an amplifier back to its input and turn up the volume. This was the core technique in David Tudor’s earliest electronic music, and it had also transformed the Tandberg tape recorder I bought in high school into an unintentional instrument. (Later, this kind of wired feedback would recur in the ‘no-input mixing’ movement that arose in the 1990s.)

The cover of Semi-Conducting– Rambles Through the Post-Cagean Thicket (Bloomsbury Academic, 2025)

The pitch of feedback between a speaker and a microphone is determined by the strongest resonant frequencies of all the stages in the signal chain between the initiating energy and the ear, most significantly the hollow space through which the sound flows – an auditorium, perhaps, or an oil drum, or the column of air in a wind instrument. From an acoustic standpoint, a room is basically a big bugle with a very low fundamental frequency (since it is so much larger). The overtones of the harmonic series of a bugle can be articulated by changes in lip and breath; thanks to the behaviour of standing waves in a room, certain resonant frequencies are stronger in particular locations, and feedback can be similarly ‘overblown’ by moving the microphone or speaker. As the graphs in their brochures show, microphones and loudspeakers have peaks and valleys in their frequency response that can affect feedback’s preferred pitches as well. Given the overtone structure of its acoustical underpinning, feedback is often harmonious – it moves in friendly intervals like octaves and fifths with the elegance of Monteverdi’s Vespers and the casual aplomb of The Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”.

I had been drawn to modal harmonies as a teenager – they had linked Terry Riley and The Grateful Dead. My affection for feedback’s behaviour, meanwhile, stretched from The Beatles’ “I Feel Fine” to Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” and my high school experiments with the Tandberg. With his instruction in the score to Cartridge Music (1960) that feedback was “to be accepted”, Cage had formally designated it as a serious musical sound source.

Every electronic musician who came of age in the 1960s or 1970s seemed to have made a piece with feedback. It was a cheap but versatile material at a time when few Americans had access to well-equipped studios. Much of Tudor’s and Gordon Mumma’s early electronic music employed both acoustic feedback between speakers and microphones, and feedback through wires. Performers of Robert Ashley’s “The Wolfman” (1964) change the shape of their mouths to articulate very loud feedback between a microphone held at the lips and a PA system. In “Wave Train” (1965), David Behrman scatters loose guitar pickups on the strings of a piano and routes them to a guitar amplifier below; the resulting feedback shakes the pickups, which add percussive accents to the sound of resonated strings.

The Wesleyan Electronic Music Studio had a pair of Sony 152SD portable stereo cassette recorders, each slightly smaller than an attaché case. If I poked my pinkie against the erase-protect tongue at the rear of the cassette-well while pressing down the record button, I could trick the machine into serving as a preamplifier that would boost any microphone attached to the recorder loud enough to feed back. As with most tape recorders, you could attach it to an external amplifier and speakers, but the Sony also had a robust internal speaker that transformed the recorder into a self-contained, portable sound system. Its built-in limiter tamed feedback’s shriek, reducing it to a mellow sine wave that could be nudged from pitch to pitch by moving the microphone. (A limiter presents a good example of negative feedback: a portion of the output volume is subtracted from the input signal so that the loudness never exceeds a set threshold, preventing the clipping and distortion typically associated with the positive feedback of an out of control PA.)

I ran feedback through as many variations as I could invent or discover. I carried the Sony outdoors and ‘played’ culverts with feedback, as if they were huge trombones. I used contact microphones to cycle feedback through solid objects such as tables, walls, floors, and tree trunks. I resonated the air columns of wind and brass instruments by embedding tiny lavalier microphones inside mouthpieces and feeding them back with loudspeakers; as performers changed fingering or slide position, or moved the instruments in space, the feedback would break to different overtones. Later I substituted small speakers for some of the mouthpiece-mounted microphones, transforming trombones and tubas into ‘speaker-instruments’, and manipulating feedback between pairs of instruments without the need for a PA. Feedback became the gift of which I never tired.

Nicolas Collins is a composer based in Berlin and Massachusetts. Semi-Conducting – Rambles Through The Post-Cagean Thicket is published by Bloomsbury Academic. Wire subscribers can read Marc Weidenbaum's review of the book in The Wire 493 in the online magazine library. Buy a copy of the print edition of the magazine here.

Leave a comment