Read an extract from Strike While the Needle Is Hot: A Discography of Workers' Revolt

January 2026

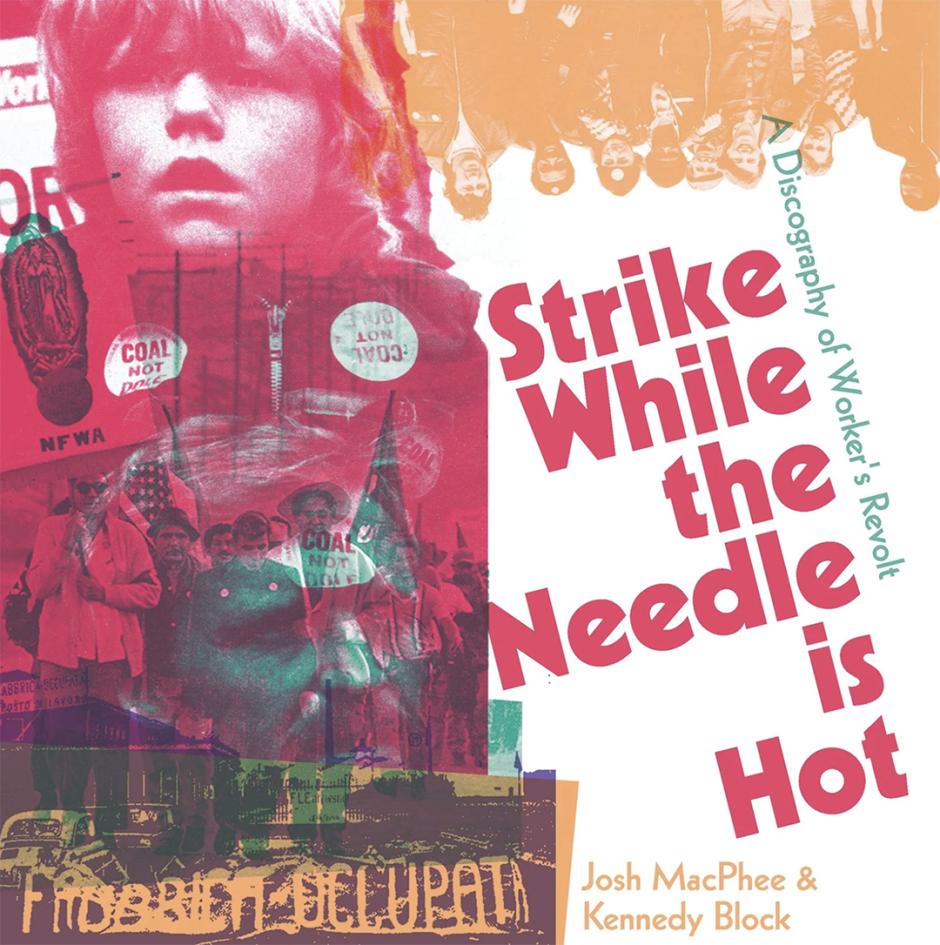

The cover of Strike While the Needle Is Hot.

In an extract from his new book, co-authored with Kennedy Block, Josh MacPhee outlines the role of workers' songs and the making of records in supporting labour movements in the US

If producing a record is a tactic, and winning a strike is the goal, then what is the strategy? From studying these records, it’s clear that the hopes for them are sometimes singular, other times multiple, often overlapping, and almost always clearly understood and articulated by the workers and unions.The records more often than not speak for themselves when you listen to them, but as most are quite hard to find, or in languages many of us don’t speak, it’s worth trying to lay out some of the intentions for the vinyl here.

There are two dominant reasons these records are produced: first, to raise public awareness of a strike, and second, to raise money to support the strike (and the strikers, who are by definition out of work and not being paid) – this latter reason is particularly acute for the wildcat strikes, where workers are not getting any support from an official union strike fund. That said, there are plethora of other intentions you can find for these records: to document a struggle after the fact, ie, a “proof of existence”; to build capacity amongst the workers and their supporters – for example, learning how to work together, organising and accomplishing increasingly complex projects, etc; as an extension of this, to build confidence amongst workers by creating “permanent” documents of their struggle; to use as a tool to connect to other workers, often in different industries but facing similar macro economic pressures; and to reach audiences that might not read a pamphlet or a long-format political treatise, but are more than happy to pick up a record they might enjoy.

A handful of records even come out of the practice of militant research, developed by the Facing Reality group in Detroit in the 1940s and 50s, then lifted up and expanded on by autonomous Marxists in Italy in the 1960s. The idea is simple: rather than prioritising academic pursuits by outsiders, workers know their workplaces best, and can participate in the study of their own struggles, and learn from similar studies by workers in other struggles.

While the music and production of these records is surprisingly eclectic, there are some things most have in common. As we’ll see, if workers’ action produces a record, it is almost always a 7″ single, either because the strike committee doesn’t have the resources to produce something of a larger scope, or simply because most strikes don’t last long enough to collect material to fill a full LP. The length of a 7″ single is roughly a third of an LP, and its packaging half the size and a fraction of the cost, and thus demands fewer resources to produce. In the pop music market, many singles were released in blank white sleeves, or with “company” sleeves that advertised the record label rather than the specific release. You’ll find few of these here. Even if the format was small in stature, it was taken full advantage of. Almost all strike records came in picture sleeves, and many in gatefold sleeves – a double wide cover folded in half, giving the workers/union/solidarity committee twice the space to share information about the strike. In addition, it was not uncommon for the records to have additional information slotted into the sleeves: lyric sheets for sing-alongs, petitions to sign, even some oversized posters which could be hung up in apartments, or brought out to a picket line.

These documents are likely as illustrative of a particular struggle as any union newspaper or pamphlet, and sadly haven’t been given their due importance in research on worker organisation. That said, this publication is at best a cursory overview of the field, a road-map to where we might look and dig deeper in the future. I’m interested in the use of vinyl records as a form of agitprop – as can be exhaustively seen in my previously produced An Encyclopedia of Political Record Labels. The effects of my fetish for vinyl shouldn’t be understated. Beginning in the late 1970s, and gaining serious steam by mid 1980s, the cassette became a much cheaper and more versatile tool for political organising.

If we had included cassettes and CDs here, the size of this book might have doubled, at least. Both formats are much easier to produce than vinyl, and much cheaper, especially in smaller runs. There are likely many, many homemade cassettes created by workers’ strike committees that weren’t distributed beyond the picket line. I’ve been able to find a half dozen without really spending much time looking. But what little research I’ve done has made it clear that a focus on cassettes and CDs is really another project altogether, and I stand by the decision to use vinyl as a curatorial tool here. Ideally someone else will pick up the thread and follow up with a deep dive into worker-produced cassettes and CDs. But for me, and in this book, the vinyl record functions as both a marker of financial investment and a commitment to mass distribution.

Co-editor Kennedy Block and I propose there are several ways to read this book. To look at any particular entry drops you into a specific strike, more than likely a fight that has been forgotten, at least by those who weren’t active participants. Like the records themselves, the entries are modest time capsules, historical markers of punctuated class struggle. But when taken together, they tell a larger story, one of an arc of global conflict, of the gains of workers in the 1960s and 70s, and the re-entrenchment of capital in the ’80s. We see fights for wages, shorter hours, and even worker ownership and control eclipsed by increasingly immiserated demands for factories not to shutter and pits not to close.

It’s a little brutal to listen to – in recorded real time – utopia slide into desperation, to see how neoliberalism stomped on the neck of hope for meaningful and fulfilling work, replacing it with a panicked need of workers to keep a roof over their heads. It is likely no coincidence that the tectonic shifts towards neoliberalism in workers’ perceptions of what their struggles could accomplish appear to run parallel to another big shift, this one sonic. The earliest records you’ll find in this book tend towards sounding like direct decendents of old left workers’ choruses with their martial songs and anthems (a couple even include a version of “l’Internationale”). Over the course of the 1970s we see a shift towards the inclusion of more pop idioms into the music, first in the form of folk, and then rock, reggae, and finally hiphop (or at least pop rap). While on the surface this may seem a natural progression, it exposes a much deeper and more complex process at work.

While the labour music of the 19th and early 20th century might not be the most exciting to our contemporary ears, it developed out of generations of working class organisation, both in the workplace but also the community. Songs such as “l’Internationale” and “The Red Flag” weren’t just sung on picket lines, but in union halls, at pubs, worker’s funerals, and solidarity marches. As there was little class mobility in the world, children would learn the songs from their parents, and in turn pass them down to their kids. So the shift towards pop music (primarily Anglophone pop) was not simply a stylistic one, but a shift in relationship to the songs themselves. Labour songs are a social form, to be performed and listened to in a community context. Pop music is a commodity, to be sold to individuals, who develop personal relationships to the music.

This is likely why some of the later records come off as strange, or even worse, completely corny. The records fail musically, as well as fail to give voice to any sense of a coherent working class. And this was one of the projects of neoliberalism, the bio-political replacement of any sense of collective working class identity with the atomised consciousness of individual consumers. We’re not labour historians, but hope something can be learned from the stories these records tell us.

The last 15 years have seen a huge upswing in militant labour organising in the United States, from the Republic Windows and Doors occupation in Chicago in 2008 to the huge gains made by domestic workers across the country (such as the rise of Domestic Workers United and their successful fight to pass a New York State Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2010), to the increasingly successful campaigns to organise workplaces like Starbucks (Starbucks Workers United) and Amazon (Amazon Labor Union, affiliated with the Teamsters). Music and audio documentation haven’t been a memorable part of these struggles so far, but in the social media-dominated attention economy we live in, it doesn’t take much to imagine how music could play a larger role in publicising worker action and encouraging broad support. But even if we set aside these larger promotional concerns for a moment, the records in this book exude the sheer joy of workers singing and marching together, fusing solidarity, and taking their lives into their own hands.

This is an edited extract from the introduction of Strike While the Needle Is Hot: A Discography of Workers' Revolt by Josh MacPhee & Kennedy Block, published by Common Notions Press.

You can read Dave Mandl’s review of the book in The Wire 503/504. Pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Subscribers can also read the review and the entire issue online via the digital library.

Leave a comment