Read an extract from Synths, Sax And Situationists: The French Musical Underground 1968-1978

September 2025

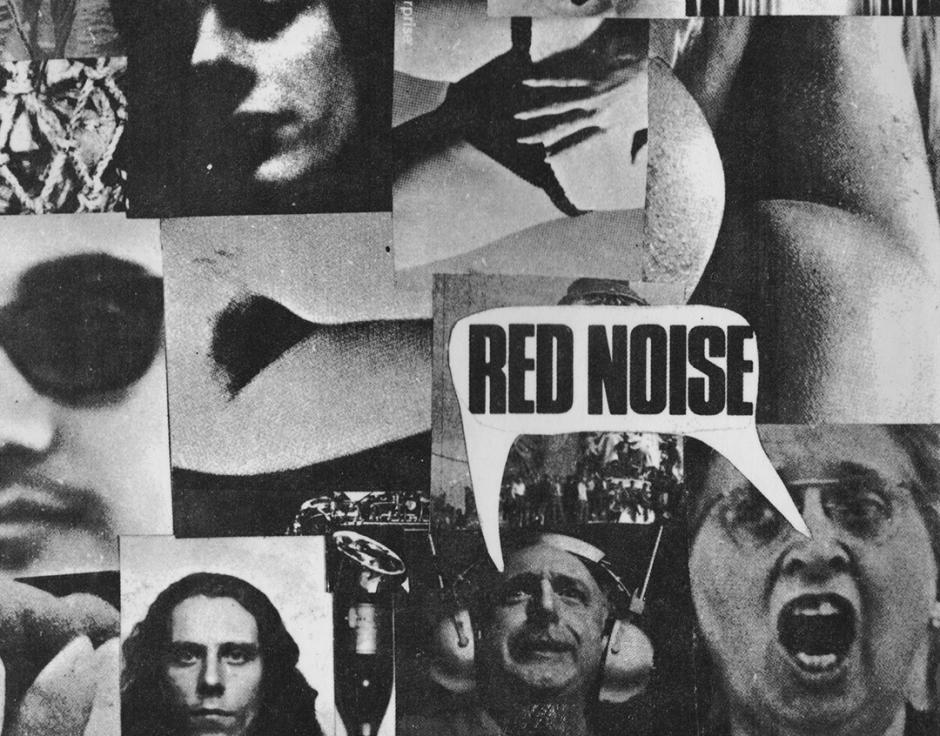

Detail from the inner sleeve of Red Noise, Sarcelles-Lochères (Futura, 1971). Collage by Patrick Vian.

In an extract from his new book, Ian Thompson charts the development of Red Noise, a collection of anarchist and communist musicians brought together during the Paris protests of May 68

While many of the French musicians of the early 70s claimed May 68 as a pivotal moment, only one band was actually forged in the white heat of the événements. They were an amalgam of anarchist and communist musicians that played their very first gig at May 68’s ground zero: the courtyard of the occupied Sorbonne.

Thierry Lewin recalled that moment a few years later: “May 1968. The students occupy the Sorbonne. An atmosphere of festival and freedom is spontaneously created. The old university becomes a small-scale model of the society of the future. To bolster the festival some young people bring their instruments, set up and play... Spring 1968 ends, but the band continue playing their music, keeping the ideas of the May movement alive. The band is called Red Noise.”

With such auspicious beginnings it’s hardly surprising that Red Noise would go on to become one of the most legendary bands of the era. Writing in 72, Jean-Pierre Lentin (himself a member of the band Dagon) called it “the first underground band... a symbol, the unrivalled reference for a whole new generation of groups”. Red Noise was both band name and manifesto; its music a sonic explosion of insurgency. Guitarist and instigator Patrick Vian was joined by Daniel Geoffroy (bass), Serge Cattalano (drums), and Francis Lemonnier (sax). Vian was son of the notorious Boris Vian (an accomplished jazz trumpeter, writer, and doyen of 50s bohemian Paris), and while the rest of the band were practised musicians he was defiantly amateur. In a 2013 interview Vian made it very clear that it was attitude and not any sense of musical “quality” that mattered to him at the time: “I wanted to show that to make music it was enough to take an instrument and go on stage. It was just a question of nerve. We’re called pre-punk and it’s true that the one thing we did was to thoroughly fuck with the sound.”

The band’s laissez-faire attitude to their own music prefigured some of punk’s anti-music ethos. Likewise Red Noise presaged punk attitude with their audience provocation. According to Vian they were determined to make music “that doesn’t try to make people forget their little day-to-day problems, but makes them realise that their problems are bigger than they ever imagined. In the beginning, a good Red Noise concert only ended when the cops intervened. We started the only group that was able to say: anyone can go stage and play, no one will notice anyway. And that didn’t bother us.”

While the band’s sound and attitude was transgressive, its members were aware that Red Noise could hardly be called a “revolutionary” band in the political sense, even though radical politics informed their music and performance. The tension between the band’s politics and music-making was made manifest on stage, as Vian was at pains to point out: “Instinctively you want to be appealing, or rather cause a reaction. There’s always an immense fear of indifference. Whatever happens, the audience has to respond. People will like what we play on stage to the extent that we exteriorise their internal rebellion. They’ll come to see a violent act... I’m for a music that’s disturbing, I don’t like music with a ‘message’. I’m against music as the ‘opium of the people’ but I’m aware that as far as our music has appeal we’ll also become the opium of the people.”

Red Noise also knew that the incendiary device of their music ran the risk of being defused by the music business, but as Vian stated: “Revolutionary songs have been sung for a thousand years, and the revolution doesn’t look like it’s coming closer. We have to try something else… I don’t believe in pop music’s revolutionary influence. Bands just want to become an advertising medium: to sell toothpaste and clothes. I don’t believe in the undermining of values, and that kind of thing: we’ve been talking about that for the last decade. My old man told me that the same thing happened in the bebop era, it’s always the same shit.”

The reaction the band elicited from audiences and the press suggested that their attempt to do something revolutionary was at least partially effective. An article in Rock & Folk testifies to the visceral impact of the band at their peak: “There’s no respite. Red Noise set off a blinding explosion... a noise that crushes your innards, that blows minds to pieces... It is raw violence, constant aggression. These long screams, this sonic madness, are possibly unique in pop music. The guitar is no longer a musical instrument, but a wooden object emitting sonic shocks with the aid of echo chambers, distortion, effects, and wah pedals. The audience is initially bewildered, then riled up.”

Musician and writer Dominique Grimaud was in the audience at an early Red Noise concert, and described the epiphany of their performance: “A scream. Slogans. Almost continuous electric guitar feedback from beginning to end. Patrick Vian left the stage with his guitar howling against his amp... I was in heaven.” Red Noise made a surprising first appearance on vinyl backing ingenue Marie-Blanche Vergne on her single “La Veuve du Hibou” (released by Columbia in February 1970). The song is a strangely beautiful collision of Red Noise’s free jazz freakout with Vergne’s jaunty acoustic ditty, sounding for all the world as if the recording engineer was tuning between two adjacent radio stations with radically different programming policies.

In May 70, just months before making its only album, Red Noise was rent in two, when Serge Cattalano and Francis Lemonnier left to form Komintern. Olivier Zdrzalik (one of their new band mates) explained the situation: “Patrick Vian considered music to be revolutionary in itself, with its shattering of structures, and that was enough. Francis Lemonnier, who was really the thinker of the group, didn’t agree. He thought it should be based on a discourse and, in the literal sense of the term, say something.” (This would be the path taken by Komintern.) To fill the vacancies left by the schism, Jean Claude Cenci was drafted in on sax and Philip Barry on drums. It was this new line up that recorded the album Sarcelles-Lochères, produced in a single day session on 28 November 1970, and released by Futura in January 71.

The album title appears mysterious until you lay eyes on a photo of the Lochères district of Sarcelles (a satellite town of Paris). In the 50s and 60s high-density housing projects held the same appeal to the authorities in France as elsewhere, and had pretty much the same end result. The liner notes of Sarcelles-Lochères bluntly states: “There are more suicides here than anywhere else.” Obviously Red Noise had a point to make.

But, there are two sides to every record – and it isn’t until the second that the significance of the title becomes clear. The first side of Sarcelles-Lochères seems to reveal a band in thrall to Frank Zappa. Constructed from a collage of skits and musical sketches (a significant number written by Phil Barry, Red Noise’s new scatology-loving English drummer), it veers from the sublime to the ridiculous. There is toilet humour (“Cosmic Toilet Ditty”, the introduction to “Galactic Sewer Song”), rock’n’roll pastiche (“Caka Slow/Vertebrate Twist”, “À la mémoire du rockeur inconnu”), free jazz (“Obsession Sexuelle”), and some surprisingly funky grooves (“20 Mirror Mozarts Composing On Tea Bag And ½ Cup Bra”, “Galactic Sewer Song”). Rock & Folk praised this side of the record: “Its structure, its form, its approach... is unique in France, and possibly in pop music... a cinematic montage, with scenarios, breaks, sped-up sequences, and collages.”

Fine as it is, side one is really only an interesting amuse-bouche to the coming feast. Side two opens with yet another skit, however “Petit precis d’instruction civique” (“Little Handbook Of Civic Education”) serves up something completely different to Barry’s toilet humour. Its call and response chant unmistakably conjures up the spirit of May 68: “The police: they’re shit! The army: it’s shit! The law, members of the jury: it’s shit! Religion: it’s shit! Patriotism: it’s shit! Capital: it’s shit!” One reviewer described this as “a rock thrown through a window” to prepare the listener for the coming sonic blast.

On “Sarcelles C’est L’avenir” (“Sarcelles Is The Future”), Red Noise finally unleash. Extra heft is loaned by the addition of organist John Livengood (of Planétarium, a band that frequently shared the stage with Red Noise) and percussionist Austin Blue Warner. Actuel lauded the track for approximating the intensity of the band on stage: “a completely free improvisation where the sound intensifies to a scream. The approach is close to free jazz without being an imitation of it. Red Noise have arrived at this fury by exploring the potential of pop music’s electrification, and screams from banlieus and grey cities raging against day-to-day boredom and alienation.”

Indeed “Sarcelles C’est L’avenir” does scream, and it bruises; it ebbs and flows in squalls and deluges like a massive storm raging against the brutalist tower blocks that made Sarcelles such an oppressively drab symbol of modern life. Sarcelles might be the future, but it’s not a future that Red Noise are going to accept without a fight. Reworking and re-contextualising Vian’s opening quote: “We want to demolish, to throw it away. If others want to reconstruct afterwards, that’s their job, not ours.”

In Rock & Folk Philippe Paringaux praised the nihilistic beauty of the track: “You immediately sense their real desire and pleasure in smashing music open, making it into a feast, bursting out in every sense, breaking out through every crack, exploring every horizon... In the 18 minutes of “Sarcelles” there is a real sense of music and of beauty, a smashed, violent, dramatic, and joyous beauty.”

“Sarcelles C’est L’avenir” is one of the pinnacles of recorded free improvisation: jazz but not jazz, rock but not rock... After 16 minutes of combative extemporisation a kind of equilibrium is reached, which is then gradually breached by screams before building to a final crescendo. Vian’s promised demolition is completed. Nevertheless, those who actually witnessed the band live consider Sarcelles to be but a shadow of the sonic fury they unleashed on stage. In his book L’underground musical en France Dominique Grimaud describes the album as “a half-success or a half-failure, whichever you prefer; still far from the sonic molotov cocktail they presented live.”

Unfortunately, like many of the first wave of underground bands, the release of their only album would prove to be the apogee of Red Noise’s career. Phil Barry left not long after the recording session. His initial replacement was Austin Blue Warner (the percussionist on the album session). He was followed by Marc Blanc (ex-Ame Son) in mid 71. Blanc was already in the band’s circle, in fact it’s his toilet that makes an appearance on “Cosmic Toilet Ditty”. He confirms that after he joined Red Noise they continued to play in their free-wheeling experimental style (“we never rehearsed, and played free with no restrictions”) but recalls only a handful of concerts in and around Paris during his ten month tenure.

The remainder of 71 saw Red Noise continuing to lose ground. There was an attempt to create some momentum at the beginning of 72, with Rock & Folk reporting that a second album was in preparation. In February Vian spruiked the band’s new musical direction in Actuel: “Today our music is built on sonic experimentation. We want to improvise, but also create four or five very short, fastidiously-rehearsed pieces. Above everything else it has to shun categories... the important thing is to make music that has some effect.” However nothing was ever recorded, and a few months later Red Noise dissolved.

In a 2013 interview Vian took some of the responsibility for the band’s downward spiral: “I lacked that Napoleonic side needed to lead a band. At one point with Red Noise, we almost managed to make music (laughs). We came to understand each other, things were going well. After that, everyone had to be directed... I hated that.” Red Noise may not have been able to maintain their explosive promise, but they do remain an important totem of the French underground. Their very existence encouraged many of the second wave of underground bands to take up arms and continue the fight they had begun.

Synths, Sax & Situationists is published by Roundtable. You can read Philip Brophy’s review of the book in The Wire 500. Pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Subscribers can also read the review and the entire issue online via the digital library.

Leave a comment