Against The Grain: Archiving anarcho-punk

December 2025

The London based MayDay Rooms’ anarcho-punk archive is a valuable resource for radical cultures and politics today, writes Seth Wheeler in The Wire 503/4

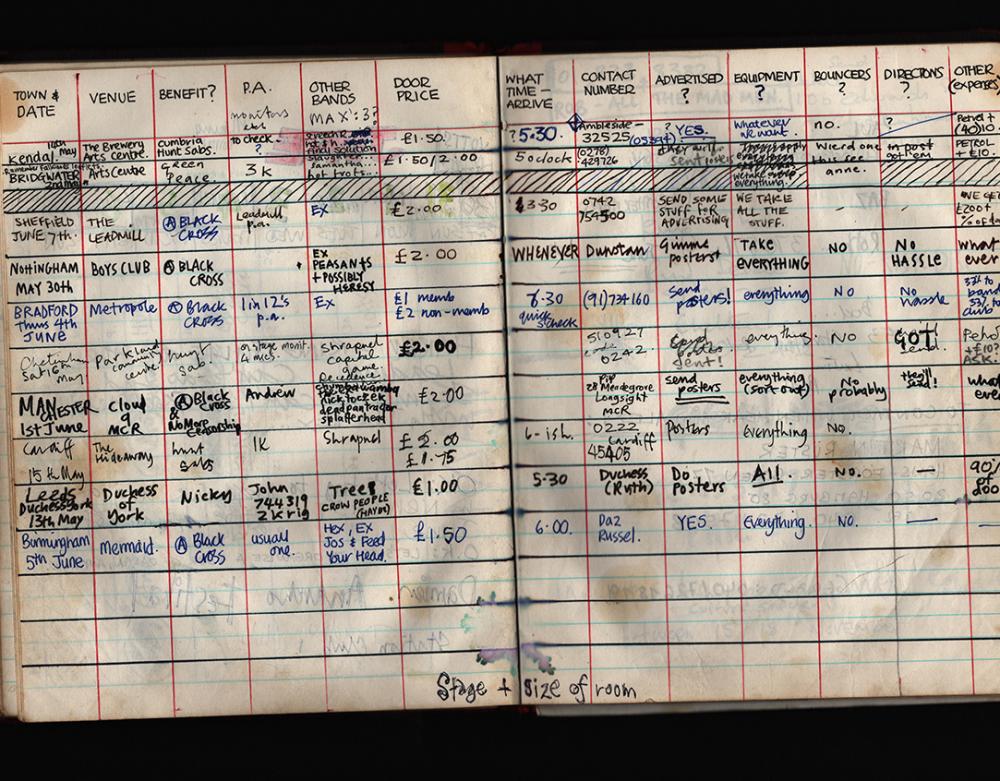

Flicking through the pages of an old diary, Dunstan Bruce, former Chumbawamba vocalist and now frontman for the agitational post-punk trio Interrobang‽, pauses. “This will give you an idea of how immersed we all were in the wider anarchist scene in the 1980s,” he says, running his finger down the diary’s fading gridlines.

The yellowing pages are divided into hand drawn columns: dates, venues, ticket prices, local contact numbers. Under “security”, the annotations harden up. For anti-fascist benefits, security was always marked as essential. “It was a very different time,” Bruce reflects. “Gigs were often war zones – the far right were very active.”

Chumbawamba's tour diary. Photo by Seth Wheeler

We’re standing in the Fleet Street offices of MayDay Rooms founded over a decade ago as “an archive, resource and safe haven for social movements, experimental and marginal cultures and their histories”. Its holdings form a vast paper topography of refusal over 100,000 flyers, bulletins, pamphlets and minutes tracing the history of the anti-authoritarian left. Much of the material is British but threaded with transnational currents: together they form a living diagram of insubordination as it travelled the world.

While open to researchers and the public, MayDay Rooms’ main aim is to connect this material to current struggles, teasing out what lessons recent ones may hold for militants today. Its free programme of screenings, workshops and discussions extends the archive outward: archive as feedback loop, not mausoleum.

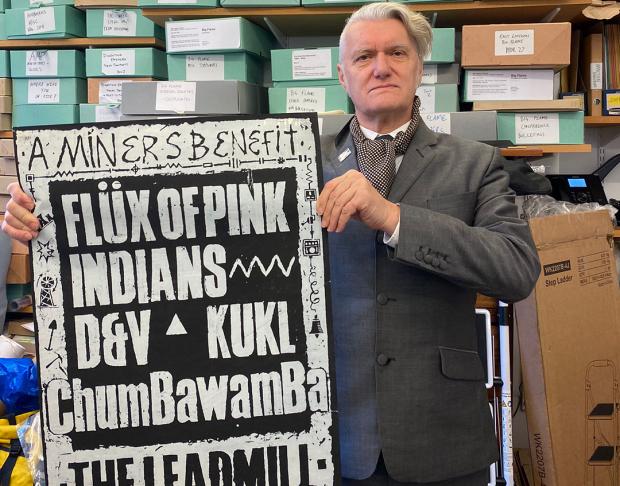

While historians accept punk injected new energy into Britain's ageing anarchist milieu at the end of the 1970s, this convergence largely remains under-documented in the archive. Beyond the odd leaflet or review, anarcho-punk’s effect on anarchist practice has largely escaped the record. To counter this, MayDay Rooms has issued a call for materials – zines, flyers, minutes, posters – to trace how sound and political action co-evolved: what anarcho-punk did to politics, and what politics it created. Among the first to respond were former members of Chumbawamba, whose origins lie in that milieu.

By the time The Sex Pistols imploded in 1978, much of the press had declared punk dead. For those who had only just swapped flares for safety pins, this closure felt premature. Taking “Anarchy In The UK” not as irony but as directive, thousands began to organise. At the centre of this stood Crass. The Epping based art collective were the first to fuse punk’s anti-authoritarian energy with a DIY sensibility. Crass’s self-organised tours reached beyond the rock circuit into squats, working men's clubs and village halls, extending punk’s reach outside the metropolitan grid. Their self-released records unfolded into manifestos, essays and posters, transforming the LP into a portable agit-prop device that many would emulate. Crass’s Bullshit Detector compilations – which Penny Rimbaud has called his proudest achievements – were crucial for this emerging network. “Many early Chumbawamba members featured on Bullshit Detector,” Bruce notes. “We tried to contact others on that release to build a national network, so as not to squander this opportunity.”

The anarcho movement was built through friendships made at gigs. Beside the amps, trestle tables overflowed with animal liberation leaflets, prisoner solidarity appeals and picket announcements. “Pen pals were really important,” declares Bruce, leafing through old correspondence. “You’d swap tapes, book tours, offer floors. These contacts became the backbone of the movement.” Bands adopted Crass’s austere visual grammar: stencils, projections, slogans collapsing poetry and polemic. Performances became calls to mobilisation. By the early 1980s, anarcho-punk formed an archipelago of resistance sustained by squatting and dole autonomy.

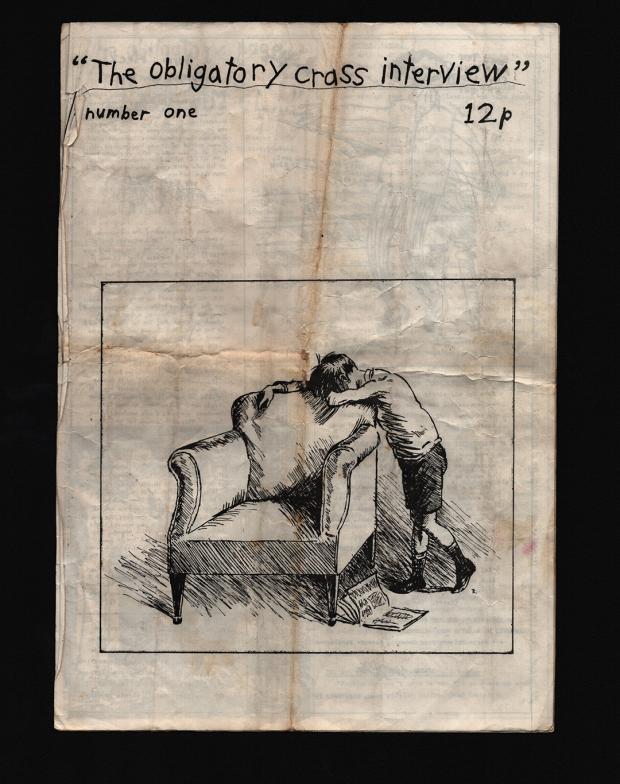

Soon the energy spilled onto the streets. Crass helped coordinate the proto-Occupy Stop The City protests in 1983-84, that blockaded London’s financial district. “We attended the first one in 83,” Bruce recalls, “then we organised the Leeds one in 84. Hundreds came out.” Zines provided another infrastructure. “Our first fanzine was called The Obligatory Crass Interview,” he smiles.

The first anarchist bookfair, held at the Wapping Autonomy Centre – funded by sales of a Crass and Poison Girls split single – made visible the generational encounter between punks and older anarchists. Within a few years the anarcho-punk scene had revitalised an ageing libertarian left, reanimating feminist, anti-militarist, squatting and ecological circles. Its graphic and political energy soon bled into new formations, notably Class War, who recruited from within punks’ ranks.

“Chumbawamba had an intimate relationship with Class War,” Bruce notes. “For a couple of years we were basically their in-house band in Leeds. In the early years, we were much more concerned with single issue politics, taking our lead from Crass, whose makeshift anarchism could broadly be understood as a mixture of Quakerism, pacifism and a commitment to individual liberty. At that time we were playing benefits and engaged in direct action against the arms industry, against animal testing and the like – much like everyone else who had been turned onto the ideas of Crass. However, the second and third generation of anarcho-bands that quickly followed them shared a more developed understanding of anarchism. By the time the miners’ strike came around, many of them, including ourselves, had rejected Crass’s pacifism and the wilful minoritarianism of the scene. We had moved toward a more combative, class-conscious form of politics.”

The conditions that allowed anarcho-punk to flourish – cheap housing, lenient squatting laws and welfare benefits adequate to live on – have since been dismantled. “We took the dole as a full-time wage underpinning our activism,” Bruce says. “We pooled our resources; that money powered the band and our printing press in the squat basement. We printed leaflets for local campaigns and activist groups.”

The questions the movement posed remain urgent. How might a generation facing ecological collapse, genocide and economic precarity reinvent circuits of solidarity? How can it buy time to experiment outside of waged labour? What role could music play in collective refusal? “We were an anarchist affinity group first,” reflects Bruce, “part of a generation lucky enough to live off a functioning benefit system. We just happened to use music as our main form of propaganda. Anarcho-punk wasn’t a soundtrack to revolt – it was a form of revolt. Its organisation prefigured the world we wanted: mutual aid, direct democracy, collective action.”

Bruce opens a box labelled ‘Dissenting Anarchist Ephemera 1980s’. Beneath a pile of pamphlets lie handwritten minutes from a Stop The City planning meeting at London’s key anarcho-punk venue, Old Ambulance Station. The notes include “Crass suggests...” recommendations, demonstrating that bands were regarded as politically sovereign, equal to the activist collectives beside them.

Alongside MayDay Rooms, 56a infoshop in South London also holds a large archive of anarcho-punk materials for the public to view and engage with; this has been carefully stewarded by the artist/writer and activist Chris Jones and a host of volunteers. Sealed Records, the brainchild of Sean Forbes (of Wat Tyler and Hard Skin) and Francisco ‘Paco’ Aranda, are also redressing this subterranean history, reissuing early demos and lost recordings from the anarcho-punk scene, and presenting these alongside reproductions of zines and flyers that help to establish their social context. A recent reissue of a 1983 demo by The Passion Killers (the proto-Chumbawamba band featured on Bullshit Detector) has been warmly received among veterans of the movement and new audiences alike.

In today’s underground, anarcho-punk endures – mutated, partial, yet alive. Gigs remain self-organised in basements, social centres and DIY venues, acting as benefits and platforms. At the broader register of pop consciousness, politically charged performances – like Kneecap’s unapologetic solidarity with Palestinian liberation – suggest that live music still offers an entry point into progressive struggle. “The unresolved question,” says Bruce, “is how music can become a strategy again.”

The anarcho-punk archive offers a working hypothesis: when music detaches from commodity logic and reattaches to social purpose, it becomes infrastructure, the connective tissue through which radical movements coalesce and alternative futures are rehearsed. Against the backdrop of today’s crises, the task remains the same: to transform music into militant organisation, a building block for a kinder, more equitable world.

A version of this essay appears in The Wire 503/4. Wire subscribers can also read it in our online magazine library.

Leave a comment