Against The Grain: Derek Walmsley on how Spotify distorts genre histories

July 2025

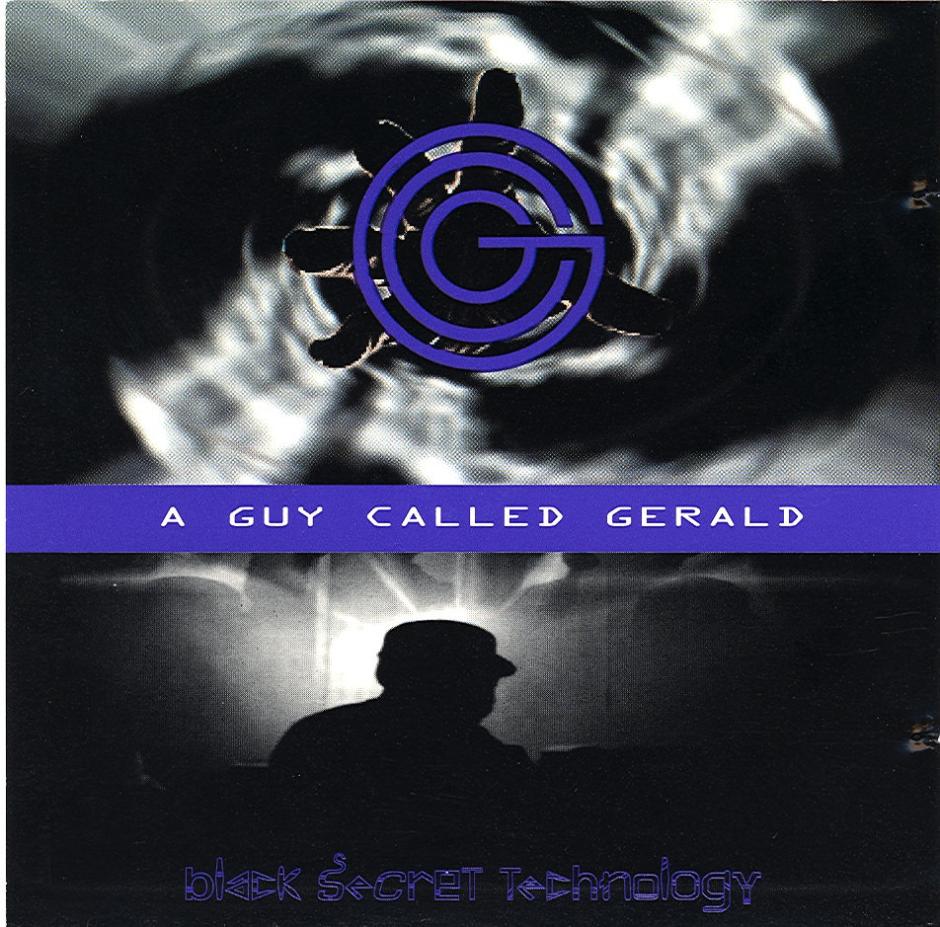

Sleeve art for A Guy Called Gerald’s Black Secret Technology (1995)

Spotify’s partial catalogue of underground genres such as grime and jungle distorts listeners’ understanding of their history, argues Derek Walmsley

“We really want to soundtrack every moment of your life,” pronounced Daniel Ek, co-founder of Spotify, back in 2016. Over the last 15 years, the streaming giant has pushed its listeners towards playlists for studying, working, working out, chilling, even sleeping. The front page of Spotify’s website throws weekly, even daily updates of music at the user, all with the goal of keeping them locked into its app for as long as possible every day.

But the obsession with the present moment has meant that Spotify, the world’s most powerful music streaming service, has become disconnected from the past. In the case of genres such as drum ’n’ bass, garage and grime, it’s starting to blur and even distort the histories of how they came to be.

Although it’d be unrealistic to expect a music streaming service to be complete – that would carry its own risks of monopolisation – it’s striking that there’s barely a trace on Spotify of A Guy Called Gerald’s Black Secret Technology (1995), one of the most influential drum ’n’ bass albums of all. A search for A Guy Called Gerald will instead yield a smattering of his house tunes, a Haçienda Classics playlist, jungle anthems by other artists, and fan playlists inspired by his work. It’s a simulacrum of Gerald’s career, a vague impression of being in the thick of the scene but with nothing at the centre. Similarly, the catalogues of some of the most creative labels in drum ’n’ bass, such as LTJ Bukem’s Good Looking, 4Hero’s Reinforced and Goldie’s Metalheadz, are present on Spotify only as ghostly copies of themselves, via a confusing mish-mash of tracks on compilation albums and mysterious digital reissues accompanied by perfunctory artwork.

Liz Pelly’s recent book Mood Machine: The Rise Of Spotify And The Costs Of The Perfect Playlist tells how the company initially started with the aim of selling ads – music would merely be the content around which to push them. The roots in advertising fostered a faith in data and metrics that, in time, came into conflict with editorial values of fairness and transparency. As Pelly explains, despite Spotify’s techno-utopian narrative that all music was on a level playing field, its use of major label reps and artist liaison teams provided a fast track for hyped artists to get exposure, replacing mainstream radio with a brand new system of technocratic gatekeepers. The obsessions with statistics also boosted songs which received the most listens, creating a feedback loop where popular songs were duplicated across more playlists, creating yet more listens, while deep cuts get pushed to the sidelines.

Regular listeners to streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music and Amazon will recognise the sensation of songs served up on auto-play getting steadily more generic from one track to the next, offering crowdpleasers in the hope of keeping people on the app. While services like Spotify give the appearance of infinite choice, in operation they revert to the familiar.

When this is applied to an underground movement such as drum ’n’ bass, important parts of its history go missing or get mixed up. Ragga jungle hits like Uncle 22’s “Six Million Ways To Die” or Trinity’s “Gangster” are elusive. Searching for Shy FX and UK Apachi’s landmark anthem “Original Nuttah” points you to an inferior 25th anniversary remake on a different label. The work of many innovators such as Danny Breaks, Krust, DJ Crystl and Peshay is often listed with a release date well after it first dropped, giving the impression that drum ’n’ bass rose to prominence years after it actually did.

Some of this confusion is caused by the ad hoc business arrangements and magpie sampling practices of the early 1990s, where tracing (and proving) the ownership of particular tracks is difficult. Combined with the layers of data analysis and gatekeeping at a corporation such as Spotify, however, and independent music becomes marginalised in favour of the sanitised, commodified and establishment.

The omissions are even more striking in the UK’s grime scene. In grime’s early days, quickfire white label 12"s often dropped outside of any formal relationships of record labels and contracts. The work of groundbreaking MC D Double E, whose tracks with Newham Generals, Aftershock and Jammer sounded like nothing else in the early 2000s, is only present on Spotify from around 2010 onwards, a faint echo of the music that first made him a star in the first place.

Whether it’s grime, drum ’n’ bass or even hiphop, Spotify struggles to keep track with music that involves MCs. The greatest ever posse cuts in grime and hiphop – Jammer’s “Destruction VIP”, and The Juice Crew’s “The Symphony” – are both absent from Spotify, which feels too significant to be a coincidence. The chaotic social energy that makes these artforms so exciting is hard for mainstream platforms to keep pace with.

It also seems to struggle with vinyl. The credits, addresses and shout-outs that are important info on the back of a 12" get missed or lost in the thumbnail images that Spotify and other apps use to represent artists and their work. Ironically, the wild west of YouTube, where sleeves are shown in full, and there’s space for miscellaneous information underneath, reps artforms like drum ’n’ bass, grime and hiphop more faithfully than the walled garden ecosystems of music streaming platforms.

When it comes to the legacy of British underground music, experiencing it through Spotify is a little like viewing art or history through those immersive visual and video experiences that are springing up around exhibition centres across the UK. They present commercialised versions of the messy business of history, rounding off the rough edges and pleasing the crowd rather than giving you the full story. Curation becomes subservient to metrics. When the aim is simply to hold the user’s attention, real stories start to recede into the past.

Comments

Does... does he not understand how a service like Spotify works? Spotify are not omitting tracks. The copyright owners have not uploaded the music for whatever reason... they don't want to be there. They don't have the masters. Whatever.

If there's errors in the release info, or the thumbnail, blame whoever uploaded the files to their digital distro. The label or the producer. Or someone who is pretending to be one, or both.

Spotify is a streaming platform. It's the most popular one, and from an artist POV, a pretty miserable one. But pointing a finger at Spotify for whatever music not being there is just stupid.

it’s a bit of a broken record railing against the mega streaming platforms and their auto playlists, and whilst it’s good to put them into perspective, it’s a bit like ‘News at Ten doesn’t tell me everything about what is going on in the world’. I happen to have got that guy called Gerald lp when it came out, cause I already knew about 808 state, but did I frequent off radar clubs in London suburbs or know the ‘scene’? No! Do I find amazing obscure’ electronic stuff from 70s or earlier on Apple Music? Yes! Do I find really inspiring current day stuff a few rabbit holes away in streaming land? Yes! So whilst for example run-off references had their moments of thrill, ultimately they were/are messages for their time, and perhaps their context is no longer that relevant for anyone who is not a historian? Enjoy the music :-)

Mike

Leave a comment