All Ears

January 2025

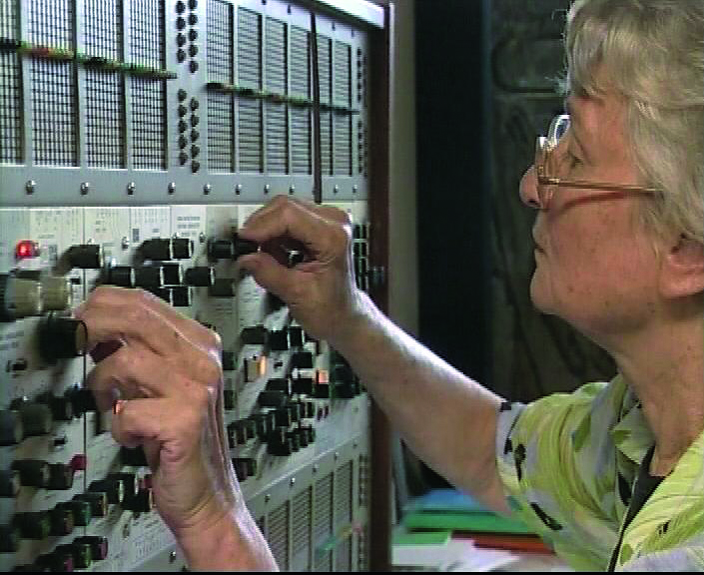

Éliane Radigue in the documentary Virtuoso Listening (2012)

In The Wire 491/492, Louise Gray recalls developing a new relationship to sound while bed-bound in hospital following an accident

This is a piece that I never anticipated writing. Dictating from a hospital bed, I am thinking about how I might inhabit sound and music instead of them inhabiting me. This involves a radical shift from listening to and internalising music, to being held externally in a sonic landscape. Surprisingly, the constant bleeps of hospital machines and the bustle of people often have relatively little impact on my thinking. Even within this cacophonous environment there are points when I find myself able to think very clearly about the shape and timbre of sounds going on around me: the compression device on my leg, the alarms that until recently were hooked up to my vital functions.

One of the central things that conversations with Éliane Radigue taught me was that sound and music unfold in space; and what you hear depends not only on the type of space it occurs in, but also the when of it, meaning at which point you, the listener, encounter the sound. This is axiomatic. After all, we know the nature of a sound changes according to what we might call its lifecycle, from the attack to its plateau to the eventual decay into silence. So sound in this way is volume in volume, or to put it another way, amplitude in cubic space. Radigue’s insistence on the importance of space in the unfolding of sound and its harmonics has often made me think of a grid of sound, occupying a cubic space in which a note and its partials may be logged accordingly. The important thing is that the grid is dynamic; it is always dynamic.

Perhaps all this sounds somewhat theoretical. It is not, of course, because we are talking about the positionality of the listener. But it became incredibly real to me in the hours following an operation, the first of two in quick succession, to stabilise my spine following an accident. Lying immobilised in a hospital bed, this grid felt extraordinarily real to me, and it was as if I could see and hear the points of sound lighting up in the nodules of this 3D topology. Lying like this, I felt myself decomposed rather than composed, with the atoms that constitute me dispersed, rather than concentrated in that mass which composes the physical and mental me. My strong feeling was that I was the object mapped out in that grid, wondering at the newness of this sensation, noticing it but also striving to recompose myself through sound.

For me, it was automatic to parse this through thinking about Radigue’s OCCAM Ocean, a series of acoustic works that she began after leaving the electroacoustic medium behind in the early 2000s. This feeling was reinforced for me as I listened to Radigue’s OCCAM Ocean Delta XV played by Quatuor Bozzini. It had been included on a playlist created for me by my dear friends Anne Hilde Neset and Rob Young (both former staff members of The Wire). As I listened to this OCCAM piece from an iPhone dangling above my head, I saw quite clearly the sound object that Radigue had created within this particular space. It was palpably real and three-dimensional to me, an ovoid shape, pulsing and translucent. I was struck suddenly by this vision. It suggested to me a strong ideational link to Radigue’s very early work with Pierre Schaeffer in the 1950s, when she was an intern in his Paris experimental studio. Part of Schaeffer’s acousmatic activities led to the creation of musique concrète: through the practice of reduced listening, the sound source is removed to reveal the sound object, or the objet sonore, the pure sound itself.

Before my accident, the last piece of music I listened to seriously was Beatrice Dillon’s Seven Reorganisations. This followed conversations I had had with Dillon about her orchestral piece for London Symphony Orchestra, Sift, which was premiered in late October 2024. I only heard rehearsal tapes of Sift, but together with Seven Reorganisations Dillon’s pieces came alive and became comprehensible to me in this grid where sounds panned from one side to the other to create a three-dimensional form which, like the OCCAM Ocean mentioned above, was alive, dynamic and pulsating and coloured with infinite gradation.

In the performance of an OCCAM the sound source is not stripped away; the musicans sit before you, and you are aware of their virtuosity. But close your eyes and you hear these sounds coming into being, interacting and playing with one another in a huge acoustic architecture that vibrates the space and then slowly falls away.

Throughout my continuing recovery there have been points where I felt as if I were the sound object itself, floating in a most peculiar way. Thinking again of how the OCCAM pieces work in ensemble, I marvel at how each musician’s path joins with that of their fellow players to create new combinations and recompositions as the notes and their constituent harmonics come into being and then recede. Recomposition is an integral part of the alchemy of Radigue’s approach to music. It is an ongoing act not just for the OCCAM series but also for me.

This essay appears in The Wire 491/492 along with many more critical reflections on 2024. To read them, pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Wire subscribers can also read the issue in our online magazine library.

Leave a comment