Receiving the timecode: André Vida on playing alongside Jemeel Moondoc

September 2021

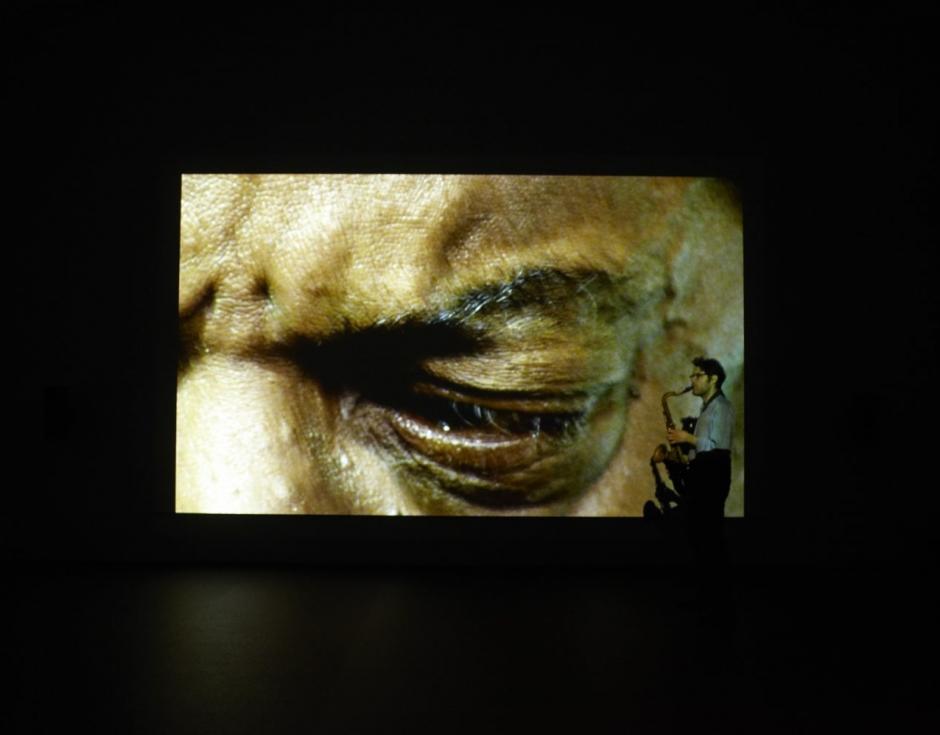

André Vida performing alongside Anri Sala’s film Long Sorrow featuring Jemeel Moondoc, Serpentine Gallery, London 2011. Photo: courtesy Serpentine Gallery

Following the death in August of US saxophonist Jemeel Moondoc, fellow saxophonist André Vida recalls their virtual duets in galleries in London and New York

Alto saxophonist and composer Jemeel Moondoc, who died on 29 August aged 75, started out as a member of Cecil Taylor’s influential Black Music Ensemble at the University of Wisconsin back in the 1970s. When Taylor moved to Antioch College in Ohio, Moondoc followed, and he subsequently moved to New York where he became a vital part of the city’s loft scene, meeting musicians such as William Parker, Roy Campbell and Rashid Bakr, who later formed his Muntu Ensemble. In the mid-1990s he experienced a resurgence with the Eremite label releasing several of his albums, and through the 2000s he performed with his Jus Grew Orchestra, New World Pygmies, and in duets with Connie Crothers, Dennis Charles and Hilliard Greene, among many other ensembles.

Moondoc’s improvisations channel blues and free playing into passionate expressions of the moment, spinning out the end of his breaths with ever-renewing rhythmic invention. His compositional intention is precise and focussed, and his pieces bounce with arpeggiating cadence and lyrical line.

Although we never met in person, I have performed roughly 1000 times in duet with him through a film that Anri Sala made of Moondoc, at installations at the Serpentine Gallery and New Museum. The film, Long Sorrow, features the saxophonist hanging out of an 18th floor window on the top floor of a large social housing complex in Berlin, and he improvises with the situation.

It all started at Sala’s show at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2011. I played with Moondoc alongside a large scale projection of his solo, with his saxophone blasting out from fixed speakers, for seven to ten screenings of the film each day. The strange irony of our encounters is that while he is a unique and powerful improvisor, the film and his solo never changes. I anticipate and follow his shifting cadences with my steps, moving backwards and forwards in cold grey museums. I absorb the never ending timecode of the film and Moondoc himself, but he has never received mine. I have lived inside his cinematic presence for short eternities of ruptured time. Jemeel's solo alto sax improvisation in the film is complex and beautiful, and he expresses a range of musical depth, and his voice sings and yells in unity with the sax.

As the camera pans slowly to the open window, we see the back of his hanging dreadlocks, and atop them lies a laurel of green leaves and white flowers. When the bells from a nearby church start to ring, he plays with them, anticipating and responding to their gallop. Then he stops playing. The silence is beautiful. When he eventually breaks the tension, he yells out and sings with very short sax punctuations, and his body becomes the instrument. To hear Moondoc punctuating the silence with vocal articulation invokes the continuum of blues saxophonists like Dewey Redman, who added their voice to the sax sound. Moondoc’s sax sound is extremely sensitive and bold at the same time. His breaths reveal sprawling rhythmic landscapes and topographies marked with smears and rolling phrases, punctuated with honks. The complexity of it is such that any attentive listener can hear different details in the solo each new time.

After around 400 performances, I began to learn how to make it seem that the film is responding to me. Anticipating the phrases that Moondoc completes, I learn how to float in an automated trance through the performance, losing any perception of linear time in the repetitive rhythm of the film and exhibition. From a journal entry: “The saxophone sounds arc over me like the skeleton of an ancient whale, each bone existing independently but held together by the path of my feet. A spine shifting continuously to avoid curious children, art insiders and confused park tourists.”

In one shot from the film, Moondoc hangs small in the bottom of the screen – I sometimes kneel in front of him, covering him with my shadow, then spin out from the screen, and Moondoc peaks out. His face fills the screen like a giant, channeling his breaths at full intensity with blinking rolling eyes. I whirl around the gallery to activate a moving acoustic shape in the room in the presence of his imposing scale. In close up, the white hairs reaching from his outer temple descend to dreadlocks and his gesticulating mouth reveals a silver crowned tooth. Singing and playing, his voice and sax sound as one instrument. A last eyeball rolls upwards and his flower crown descends into the trees. At the end of the film, the empty window sits alone. In the distance, an airplane crosses from left to right across the screen, disappearing into it.

Five years later at the New Museum in New York, I perform another 500 times with Long Sorrow during Sala’s exhibition there. My connection to the solo intensifies in a new installation with the back of the screen modulating shades of grey and light according to the volume of his solo. The second floor of the New Museum is split in half with a large projection screen. From the elevator, the spectator enters the centre of the room, first encountering the screen from its perpendicular edge. On one side, the fluctuating light and greys turn the sound of the solo into a mirrored abstract visual presence from the Long Sorrow projection on the other side.

I would spin on both sides of the projection screen to throw my sound around the room and activate the high ceilings. When spinning, I become blind to the projection, and the sound of Jemeel’s music pours out, leading me through the gestures of the ritual. The solo accompanies the film like a gold standard, stamping its value onto the images and then stamping the world with its unique representation of time.

Long Sorrow captures Jemeel's presence and performance in 13 minutes. Having seen the film so many times, I am very happy it exists. It captures his breathing and musical thinking so clearly and offers an immersive experience of his extraordinary suspended song.

Wire subscribers can read an interview with André Vida as well as Louise Gray’s review of Anri Sala’s 2011 Serpentine exhibition in The Wire 334, which they can access via our online archive.

Leave a comment