The old music and the new fascists

July 2024

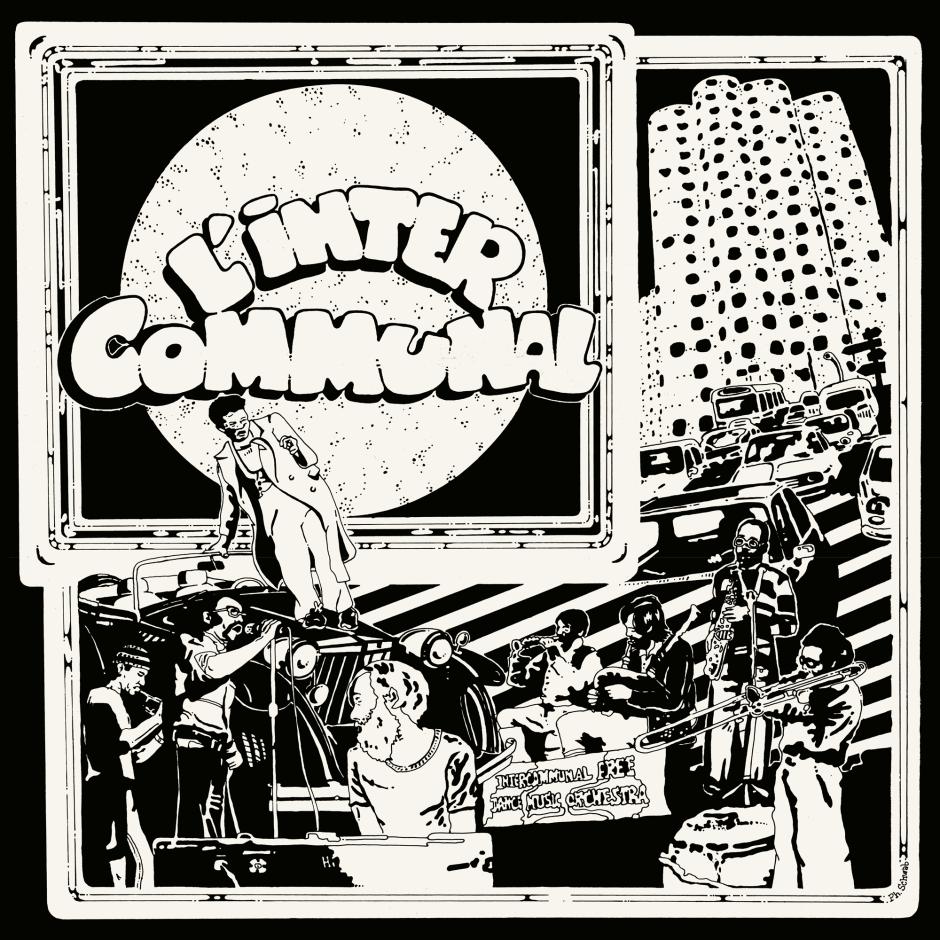

Cover of L'Inter Communal by Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra (1978, reissued 2024)

As the far right looks set to gain ground in France’s elections on 7 July, Pierre Crépon looks to the reissued catalogue of pianist François Tusques’s Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra of the 1970s as an example of multicultural resistance

There is a strange irony in seeing pianist François Tusques’s work with The Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra finally resurface at this precise moment. Tusques was one of the key figures to emerge from France’s time as a free jazz hot spot at the turn of the 1960s. But he made some of his most unique music in the 1970s with the Intercommunal, a group that successfully mixed musics from many sources, ranging from North Africa, to Spain, to France’s Brittany region, to North America.

Now, 50 years on in 2024, France is on the threshold of its first far right government since the collaborationist Vichy regime of the Second World War. The movement that is trying to seize power is a rebranded version of the Front National, a party spawned in 1972 by a neofascist grouping called Ordre Nouveau. Adorned with Celtic crosses, Ordre Nouveau was a proponent of street violence. Often, it directed it against the far left organisations active in post-1968 France and to which Tusques had ties.

According to drummer Noel McGhie, Tusques and Ordre Nouveau crossed paths at least once. The scene took place at the Faculté de droit, rue d’Assas, in Paris. The musicians were about to play after a film had been shown, when cross-adorned far right militants attacked, forcing an evacuation by firing a gun. The event was rescheduled shortly thereafter, this time with the presence of substantial leftist security.

Sources are not abundant, but this attack can likely be placed to early March 1971, when Tusques and McGhie were to appear with singer Colette Magny at an event held in solidarity with the Black Panther Party. More violence followed in short order, notably a massive clash between Ordre Nouveau and Trotskyist militants attempting to stop a meeting at the Palais des sports. Neofascists inside were treated to some Wagner while they waited for the moment to shout “France to the French”.

If this past might now seem very distant, perhaps quasi-mythological, some of its components have retained more currency than others. Racism as a motor force is centrally in evidence in France, the US, and countless other places. On the other hand, the current cultural climate carries nearly no information about the nature of Trotskyism or the world communist movement of which it was a part. Marxism-Leninism, the Sino-Soviet split, contradictions as forces of development, or names such as Huey P Newton call for extensive definitions. History has a way of phasing out some of its forces, as has been the case for much of what then made up the left, much of which is now understandable only after an active research effort.

Perhaps somewhat ironically, as art was rarely granted a central position in the political processes of the left, what remains most immediately accessible today is the culture that did emerge from such movements. Tusques and The Intercommunal Orchestra were prime examples of it. After the years during which free jazz reached its most feverish pitch, in the 1970s the question was how to make a music that could be more popular, more easily understood, and relate more closely to the local French context.

The answer found by Tusques and his colleagues was The Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra, whose name provided a mostly self-explanatory outline of the project. The term ‘intercommunal’ referred to writings by Black Panther Party leader Huey P Newton. Locally, it was taken to mean the grouping together of the different communities living in France.

In practice, this meant that a soprano saxophone and a bombarde – a traditional Breton instrument of the oboe family – could stretch out together over an electric piano and congas groove, as heard on Le Musichien. During a solo included on Volume 3, Tusques moves from Vietnamese and Chinese material to the Paris Commune of 1871. The band could incorporate elements of blues, biguine, North African music, play Charles Mingus’s “Fables Of Faubus”, or dedicate a piece to Egyptian singer and oud player Sheikh Imam. On paper, this should have been a recipe for disaster, but it worked. Guinean saxophonist Jo Maka, Togolese trombonist Adolf Winkler, Catalan singer Carlos Andreu, Algerian percussionist Guem, the Marre brothers, and many others contributed to the band.

For many musicians, making ‘political’ music simply consists of superimposing material on forms that have long been sealed shut, resulting in works barely distinguishable from their non-political counterparts. The Intercommunal tried to “question the very foundations” of the music its members had previously played to build something new, looking towards socially functional popular forms as starting points. In the process, the band created music that was inseparable from the function it sought and could not outlive it.

So, this old music is coming around again for another spin. Of course, this very small event has no bearing on the larger historical moment. But perhaps the old music, coming from a time that gave currency to the idea that there was no such thing as art standing above politics, asks a timely question. When society moves to the right, so does culture. Can we identify the forms that will undoubtedly remain impervious to the swelling, violently racist and exclusionary worldview that is at the heart of far right ideology, with or without the Celtic cross?

The Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra catalogue is currently being reissued by French label Souffle Continu.

Leave a comment