A different approach to structure: an interview with Robert Cox

May 2021

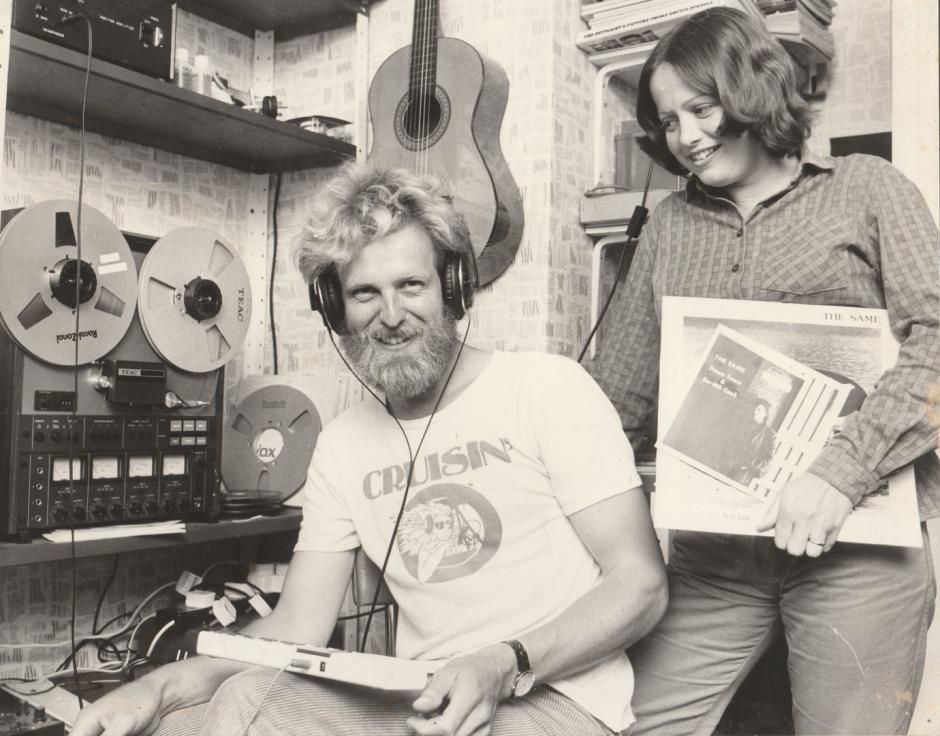

Robert Cox (left) and Florence Atkinson of The Same, Felixstowe, UK, 1982. Photo Nick Garnham/Felixstowe Times

As Freedom To Spend reissue The Same’s 1981 album Sync Or Swim, multi-instrumentalist Robert Cox talks to Dave Mandl about his minimalist DIY recordings and his signature group Rimarimba

The music of Rimarimba, mainly a vehicle for Suffolk multi-instrumentalist Robert Cox, is more widely known than the work Cox has produced under his own name or in collective settings, including his early group The Same. But the latter ensemble’s Sync Or Swim, originally released in 1981 on Cox’s Unlikely Records label, gives a foretaste of the sound that he and Rimarimba would become recognised for: long, repetitive pieces combining elements of Terry Riley-esque minimalism, French toy pop, Frippertronic drones and Synclavier-era Frank Zappa, as well as (unlike Rimarimba) guitar pieces evoking the bucolic instrumentals of Leo Kottke or John Renbourn. With Sync Or Swim set to be reissued on the 40th anniversary of its release by Freedom To Spend – home of new editions of all of Rimarimba’s recordings – Cox discussed his work with Dave Mandl via Skype from his Suffolk based studio.

Sync Or Swim was released in 1981, an exciting time for music. There were loads of odd hybrids starting to appear, all kinds of unusual influences creeping into so-called rock music. On Sync Or Swim I hear krautrock, minimalism, computer music, folk. What were you listening to at the time?

Certainly English folk music. There’s a lot of that on it, just the way English music is put together. The conversation is still ongoing about the difference between English psychedelia and American psychedelia. British psychedelia is rooted in folk music and American psychedelia is rooted in the blues. What we were listening to then: Zappa, Grateful Dead, Eno. John Fahey was someone who made me think, I want to make that noise. Him and Leo Kottke initially.

I also hear shades of Sandy Bull, that kind of longform psych/raga.

I’m aware of him through the Takoma collection, but he’s not someone I’ve listened to very much. But having said that, actual raga stuff, [Ravi] Shankar and the like, I’ve been listening to for a long time. I like longer structures. I really like things that unwind over a long period of time, which is Indian classical music, obviously. And I have the same sort of interest these days in West African kora music. It’s not intro-verse-bridge-two more verses, gone. It takes much much longer to unwind.

I heard Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint on [BBC] Radio 3, the English classical music station. And initially I thought, Oh, that’s fabulous. And then I worked out what’s going on in it and thought, Oh, that’s just two lines overlapping each other. And after a while you go, bleeeeeeeaaaah. Because it’s just music for hi-fi. It’s the Terry Riley problem: it only had to be done once, because everything after In C: Yeah, yeah, that’s been done. In C was it. We all have that problem with repetitive music. Once it’s been done you’re just trying to put your own stamp on. But I still keep plugging away because it’s an approach to composition that I like – and like playing with. That moment when you’ve got a couple of lines running and you’ve got a third one over them and they all start to tumble over each other and something emerges.

Were you aware of that music at the time of Sync Or Swim?

Absolutely,and much earlier. John Peel was playing all kinds of psychedelic and modern stuff. One Saturday afternoon I’m sat in my parents’ house in 1968 or 1969 doing a painting, and at 4:40pm, on Peel’s BBC afternoon programme, he said, ‘This is Terry Riley, A Rainbow In Curved Air. I’m going home now. Bye.’ And this thing just unwound for 20 minutes. That was one of those epiphany moments. I shall remember that for as long as I live. It was just extraordinary, I sat there riveted for 20 minutes. A whole different approach to structure.

Do you feel like you rethought your approach to writing and playing then and there?

I do try to learn things by other people and I just find it really difficult. But my own stuff I can put things together that kind of sound like me and then work on them. That Riley piece had an enormous impression on me. And the English psychedelic group Soft Machine.

Who also did extended pieces...

Absolutely. It’s difficult to put in words. Miles Davis clearly took bebop in a particular direction, and electrified and stretched and he got to Bitches Brew, and everything after. Soft Machine took ensemble jazz in a completely different direction. There’s something about Third, in particular. I still marvel at that. There were possibilities in there which haven’t really gone any further. And Mike Ratledge, the keyboard player, was obviously interested in elongated compositions as well. So I think that whole Canterbury scene of English psychedelia, that was quite a big influence in what I was doing then.

I’ve noticed that there are almost never any voices in any of your recordings. Is that a conscious decision?

It’s like the difference between abstract and descriptive painting. With an abstract, you make out of it what you can. As soon as you’ve painted a vase of flowers, well, it’s a vase of flowers. I don’t have any specific story to tell. I don’t have anything specific to describe. So it’s never really occurred to me to write or to want to write lyrics, let alone get anyone to sing them.

You were using synthesizers on these early recordings, and synthesizers were much more limited at the time but still they don’t sound like obvious synthesizers. Again, was that a conscious effort?

I’ve always preferred sounds that are more like real instruments. There was an Eno line about synthesizers: ‘Using real instruments you can produce an oil painting. Using synthesizers the best you can do is produce a cartoon.’ And there’s the deus ex machina thing as well: If you use machines, you’ve got to put the ‘deus’ in there, otherwise it’s just machines. So yes, it was always a conscious effort, and it still is. Behind me here there’s a pack of synthesizers. But it’s all Emu modules, which produce sounds fairly close to real instruments. If you just program [sing-song melody] ‘dee-dee-dee-dee, dee-dee-dee-dee’ it’s like a phone. It’s pretty pointless. Again, it becomes more interesting if you get lines that tumble over each other, glitch a bit now and then. And if you can make it swing that’s even better. You need an H for ‘humanise’ on the keyboard.

Synthesizers are too ‘perfect’...

Absolutely. Far too perfect. Back to the Steve Reich problem. There’s actually a whole group of people [playing], all those fingers moving about. But it’s been rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed to the point where it may as well be a piece of machinery producing it. There’s the marvellous Todd Rundgren line, on one of the early albums. There’s a screeching guitar solo, it gets more and more bonkers, and then you hear the rap of a conductor’s baton, and Rundgren says, ‘No no no, a little more humanity, please.’ It’s the same thing with the Steve Reich, but from the other end: ‘Stop it and make a mistake!’ It’s a big problem with electronics: because you can do it perfectly there’s a temptation to do it perfectly. I have a little Yamaha device – do you know what Tenori-On is? [Shows a tablet with lights and buttons to the camera] That’s a Tenori-On. Once it’s powered up little lights run across the surface, and each time you press one of the buttons it goes ‘beep’ or whatever you selected. And you set up 16-bar repeating patterns that run down the thing. And as a quick way to get something very machine-like to play with or play over it, it’s a great little sketch tool. And we use that quite a lot. I’ll come up with a guitar idea, and I’ll program the Tenori-On as a kind of backing, play over it, and then take that away. So I’ve played over something that’s very rhythmic and metronomic. If you do that for long enough, like half an hour, you get into a kind of trance-like state and you make interesting mistakes. You drift ahead of or behind the machine rhythm, and then once you take that away you’re left with something that’s almost anchored but not quite. And then you can play with that as it’s moving about. To me that’s much more interesting than just having the beat running.

I always thought of Rimarimba’s music as having no sharp edges, and I recently learned that you have a recording called Music Without Edges, which is quite a coincidence. What did you mean by that?

Again, you can approach it in terms of abstraction: abstract painting, abstract images. If it’s a picture of a house on a hill, that’s what it is, take it or leave it. If you have stated rhythms in the music – ‘one, two...’ – that’s what you’re stuck with. If you take out the rhythm completely and are just left with a sort of harmonic wash, which is the idea of the Music Without Edges stuff, every now and then you get beat notes appearing in it. You know we’re pattern-seeking creatures amongst other things. It’s part of what we do: ‘Ah, I’ve heard something like that before.’ So you sit there with a keyboard with all the attack taken off the notes. And it’s like [makes amorphous sounds] ‘Mwwwwaaah, mwwwwaah’, and after you put down enough layers of it something begins to happen in there which you didn’t set out to do, it has just kind of emerged out of it. And I just find that approach to playing really interesting.

It removes a bit of definition, or leaves something not completely articulated.

It leaves more for the listener to do. And it leaves more for the creator to listen to as well. I have a problem with composition that, once I’ve worked out how to do something, and as I’ve got to learn the parts and play them, well, you may as well be a CD player at that point. If you’re doing stuff which is taking on a life of its own – ‘Ah, what can I add to that?’, ‘Oh, that’s an interesting harmony’, ‘Oh, so that’s where it goes!’ – that’s much more interesting than, ‘OK, I’ve got something that’s in C harmonic minor and I need to put a bass part on it, so I’ll start with this as the root note...’ It’s too prescriptive.

What prompted you to start a label? Putting out recordings is one thing, but starting a label is a whole different level of commitment, and you did that pretty early on.

Probably from the frustration of sending tapes to real labels and being told, ‘It’s close, but that’s not really the sort of stuff we’re interested in.’ And also if you’re going to go to the trouble of finding a pressing plant, and get one of your mates to do artwork, and come up with a label design, well, you’ve got a little functioning project running there which you can invite other people onto as well. So with Unlikely Records I didn’t set out to take a snapshot of early 1980s English underground/punk/DIY/psychedelia, but it turns out that that’s what I did for a year or so. But I think the motivation was mainly: ‘What’s going on out there that EMI aren’t interested in?’ And: ‘Can I draw a few more people’s attention to it?’ There’s all of this stuff going on, some of which is really interesting, and how do you get it out to people? But it’s worse now.

In the tech world, music ‘discovery’ is the problem that people are endlessly grappling with.

And part of the problem with technology now is that it puts limits on you. If you open an encyclopedia to look for something about electronics, and you happen to open it a few pages early, you wind up reading about the ancient Egyptians. You didn’t intend to, but: ‘That’s really interesting! I’ve never seen that before!’ You don’t get that with a keyboard search. There have been proposals for search engines that one in every 50 searches they should pull up something completely random. And I think that would be a brilliant idea. Trawl through all those millions of web pages and throw you one at random about cat livers or whatever.

Sync Or Swim's Sync Or Swim will be released by Freedom To Spend in June. Rimarimba’s The Rimarimba Collection was featured in The Wire's Rewind 2018 Archive Releases of The Year, which subscribers can read via our online archive.

Comments

My hero.

Cheri Knight

Leave a comment