Lunar personality: an interview with Acen

January 2021

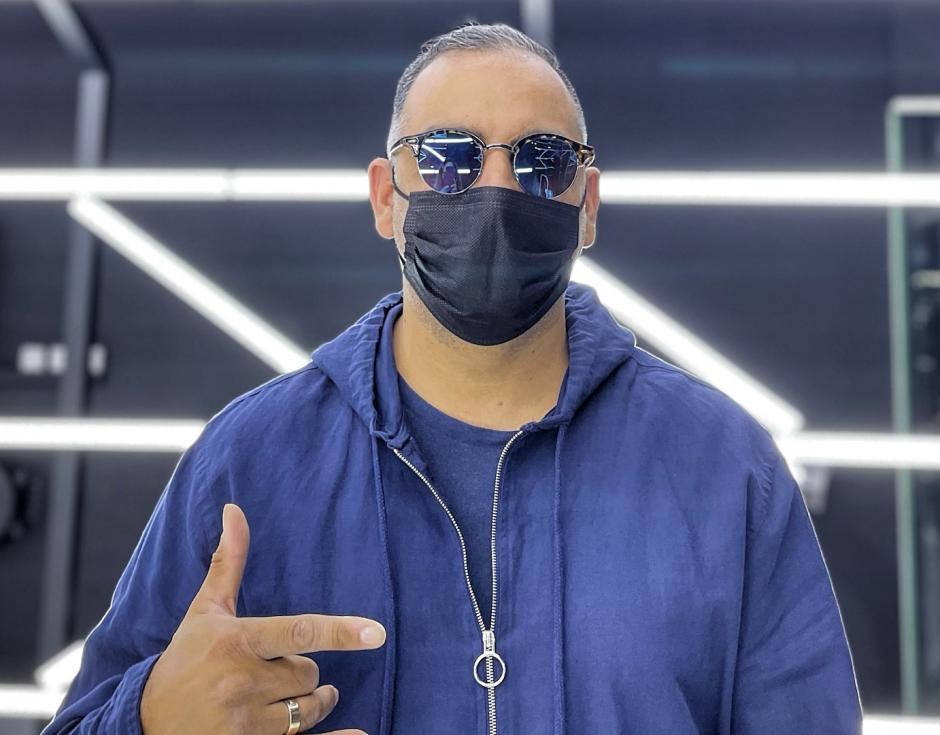

Acen Razvi

Simon Reynolds talks to the producer behind the reissued 1992 hardcore classic "Trip II The Moon"

Released by Production House in 1992, Acen's “Trip II The Moon” is widely revered as a hardcore classic. As the Kniteforce label prepares to release a six disc vinyl set dedicated to the track and its various B sides, including new remixes from the likes of Pete Cannon, Luna-C and dBridge, Simon Reynolds speaks to Acen Razvi about hardcore history and breakbeat science.

Simon Reynolds: In the 1980s there was a kind of street beats culture in the UK – almost everything came from America and Jamaica, but they got jumbled up here. That resulted in a series of only-in-Britain hybrids whose components all came from overseas. In America, the borders between scenes and genres was more demarcated, but in the UK people moved across scenes or they took bits of everything they liked and made a composite. The classic example would be B-boys into electro and early rap, who then had their minds blown by acid house, and started to mish-mash hiphop, house, techno, dancehall, dub and more into a new sound: hardcore jungle. That is basically your story arc, right?

Acen: Pretty much exactly that. In the early 80s I was doing a lot of breakdancing to electro at school discos. Then I was in a crew called Atomic Rockers, we’d put our lino on the street and practice crazy legs and windmills all summer. The Breakdance movie was a huge inspiration. Then came the harder mid-80s rap and I started to get heavily influenced by the Def Jam sound: Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, Public Enemy. Around 1987–88, I started hearing the DJ cut-up tracks by UK producers like Bomb The Bass, MARRS, Coldcut – that whole megamix scene. That’s when I started listening out for samples and becoming aware of all the old James Brown classics.

My family lived in Greenford in West London. Ealing and the Broadway was my stomping crowd. I would go to the Warwick Road parties near Ealing Common and the Haven Stables club. That’s when I started hearing acid house and then the warehouse ‘bleeps’ tunes like Nightmares On Wax, Unique 3, Sweet Exorcist.

Around the same time as those Northern bleep records, a distinctive London sound combining bleeps with sped-up breakbeats and ragga chat emerged – the germ of what would become jungle. You have mentioned figures like Rebel MC and Ragga Twins as particularly inspirational.

Rebel’s “Wickedest Sound” and the whole Ragga Twins/Shut Up And Dance set-up really cemented that fusion of raw hiphop and ragga with the warehouse rave sound. It was a melting pot of everything: bleeps, bass, breaks. Tunes by The Scientist like “Exorcist” and “The Bee” really moved me. I started religiously following labels like Reinforced, Tone Def, Kickin’, Moving Shadow, Suburban Base, XL. Liam Howlett and The Prodigy were another big inspiration – the What Evil Lurks EP.

Part of the mythology of hardcore rave is teenagers making tunes in their bedrooms with no musical training, messing about with technology without consulting the manual – leading to a lot of mutilated, mutant, so-wrong-it’s-right results. That’s not entirely a myth, as a listen to the early 90s flood of white labels would show. But quite a few rave producers had backgrounds in bands and knew how to play instruments. You didn’t, but you had studied music technology – a different kind of technical expertise.

I did a BTEC media course at West London College in Hammersmith, where I cut my teeth on film making, drama and music technology. Originally I was interested in dance and fascinated with film. But once I went into a music studio for the first time I was hooked. The equipment I had available in the early days was simple stuff – hardware synths like the Yamaha DX7 and Korg M1, and drum machines like the Roland R-8. And an Akai S950 sampler. A bit later I got the Roland W-30 workstation, which was actually way ahead of the gear we had on the course. That was the beginning of gathering samples and obscure records – anything from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to The Wiz soundtrack. Then there were the soul and club tracks – those came back then with a cappella versions and dub mixes – so it was easy to isolate a vocal to sample.

Production House, through which you released “Trip II The Moon”, was not only one of the biggest hardcore rave labels, it was as crucial a cluster of multicultural mix-and-blend as Soul II Soul or the Bristol scene centered around Massive Attack. How did you hook up with them?

I already had a demo of the first single “Close Your Eyes” sitting on a cassette and a friend knew this DJ called DMS. He liked the tune and took me round to Production House’s HQ in Harlesden, West London. It was a completely ordinary looking three bedroom suburban house in Herbert Gardens, but with two recording studios inside. The upstairs one was kitted out with synths, samplers and a tape machine, and then downstairs was a more acoustic studio with a vocal booth. Phil Fearon, the co-founder of Production House, had enjoyed chart success with the Britfunk group Galaxy in the 80s and produced some pop acts, so there was gold and silver discs on the walls of the studio, But by the time I joined, the focus of the label had shifted from street soul in the late 80s to house and rave – underground tracks.

Alongside the three Acen singles, you became a mainstay of the Production House team. You worked with DMS on his classic “Vengeance” track, remixed/reproduced tunes by the label’s core act The House Crew, made tracks like “Exodus (The Lion Awakes)” with Floyd Dyce under the name The Brothers Grimm, contributed to Russell Norris’s releases as X-Static…

After “Close Your Eyes” started making waves, I got on a roll with other potential tracks and had demos of “Exodus” and “Field Of Dreams”. But because “Close” was still hanging around the top of the dance charts, Floyd thought it would be better to put them out under a different names. He finished both tracks. Then DMS rolled in with the Run DMC “king of rock” sample, so that led to “Vengeance”. X-Static was a similar process: Russell would bring in some dub records and we’d started jamming and ended up with "Murderous Style”.

While we were finishing the X-Static EP, I was already into the process of making “Trip II The Moon”. Originally, the “take me higher” sample from Britsoul group Tongue N Cheek was the main hook, but I felt it needed something else. I hit a wall, so I went out looking for vinyl and I just happened on the You Only Live Twice John Barry soundtrack at an Oxfam shop in Ealing. I had always remembered a haunting bit of music from the James Bond film and it turned out to be "Capsules In Space”. That immediately resonated with me for “Trip II The Moon”. And then I used “Mountains And Sunsets” from the same Barry score for the “Pt 2” remix “Trip II The Moon (The Darkside)”.

That subtitle would have been one of the very first times that “the dark side” became a buzz term on the British rave scene. The track came out late summer 1992, but by the start of 93, everyone was going on about darkcore and putting out records full of horror movie samples and sinister mind-bending sounds suggestive of a bad trip. Of course there had been darker moods in techno before: Eon’s “Fear: The Mindkiller” and “Basket Case”, and before that acid house tracks like Sleezy D’s “I’ve Lost Control”. But with that “The Darkside” subtitle were you tapping into the emerging drift towards dread and paranoia in hardcore rave?

I wasn’t really picking up on anything dark side coming from the scene. It was more a double meaning to do with the dark side of the moon. And a darker reimagining of “Trip”.

Then there was third mix of “Trip II The Moon”, showcasing some dramatic piano playing. You actually taught yourself to play the instrument just for that mix, right?

I really don’t have any background in music. I don’t even know how to read or write, I just play riffs and feel out the structure. Everything is from the gut but I see it visually also, so when designing sounds or creating patterns, that helps me. With “Trip” part three, I wanted to create something more synth based and I just kept jamming until I had this piano riff.

Championing this stuff as a critic at the time, the polemical thrust was the idea of hardcore producers as untrained delinquents shredding all the rules of musicality. But what strikes me now listening to breakbeat hardcore and early jungle is actually how musical it often is. The tunes often involve multi-segmented arrangements, artfully structured with dynamics and builds, bridges and breakdowns. Partly because there’s so much use of samples from film scores, the tunes are packed with melody and interesting harmonic shifts – or clashes. With producers like you, Hyper-On Experience and The Prodigy, it’s a maximalist aesthetic, whereas most techno and house in the 90s was ‘tracky’ – one idea strung out over six minutes, subtly inflected. That kind of techno works as DJ tools: unfinished music that is completed by the decktician combining it with another barebones track. Whereas the best hardcore tunes are actually much more like finished ‘works’.

I got into the music when it was minimalist, the repetitive acid and bleep tracks – just a square-wave riff over a four-to-the-floor Roland 909/Roland 808 beat. But by the time I was producing my own stuff, it felt like the music and the scene had turned a corner with full-on breakbeats and big riff changes every 16 bars.

“Trip II The Moon” is literally orchestrated, isn’t it? The rights owners to the John Barry tunes wouldn’t clear the samples, so Production House had to hire a small orchestra to perform the parts and you resampled them.

And I sampled both pieces of music with the exact same settings I did with the original vinyl – the same low resolution bit rate. We used that to save space for memory because we always used to max out the very limited memory on these samplers. Or you could get creative with speeding up the record on the turntable and slowing it down in the sampler to squeeze more time out of the sample memory.

Your first two singles under your own name, “Close Your Eyes” and “Trip II The Moon”, were monster successes – the top one and top two dance tracks of the year in the Music Week chart, shoving The Prodigy’s “Everybody In The Place” to number three. “Trip” cracked the Top 40 pop charts too, albeit only just – it got to number 38. Was the thinking with the follow-up, “Window In The Sky”, ‘this time, let’s have a real pop smash’? There was a proper promo video, with a pair of female dancers doing amazing frenetic moves, and yourself as a shadowy figure, the rave magus. But it didn’t cross over.

“Window” was released just a bit too late. The scene had already turned a corner. I wasn’t fully satisfied with the EP compared to the first two Acen releases. I had changed my studio set-up and that slowed down the creative process. 1992 was the magic year where everything was on point. But around mid-93, it all changed. The darker, more minimalist stuff was ascendant again and “Window” still had that MAXIMALIST 92 vibe. Of all the “Window” mixes, I prefer the harder “Monolithikmaniak’ version.

Production House would actually score a UK pop number one with the 1994 release of Baby D’s “Let Me Be Your Fantasy”. That was through a deal with London Records and its dance sublabel Systematic. You also had an album deal with them – but nothing ever came out. What happened next?

Jungle had really taken over by 1994 and I was trying to make an album on that basis but London couldn’t see a commercial angle in the way that they did with Baby D. I parted ways with Production House and took some time out from making music. For a while I was really into the Mo’ Wax vibe and early big beat things like The Chemical Brothers. I made some slower tempo tunes. Under the name Spacepimp, those tunes – “K9 Law” and “The Pimp (Lino-Cut)” – came out on Clear Records. That was going back to the electro 808 bass sound and my days of getting the lino out in the street and breakdancing.

Then in 1997, I was really liking what was going in drum ’n’ bass with Bad Company, Ed Rush, Optical, Dom & Roland. I started making some tracks in that vein, one of which, “116.7”, came out on the American label Higher Education. My favorite release for them was the Eric B & Rakim “I Know You Got Soul” remixes – Ganja Kru on one side and me on the other.

Rakim is someone you’d sampled on “Trip” – “I get hype when I hear a drum roll” . Your Production House tracks are full of 80s Brit B-boy touchstones – snippets of Ultramagnetic MCs and The Real Roxanne. I’m curious, though, whether you kept on following rap into the 90s. For me, after the cartoon hyperkinesis of hardcore, the East Coast sound of Jeru The Damaja, Wu-Tang Clan, Nas, sounded really flat – one break, one loop of orchestration. I suppose the counter-view would be that these beats are meant to function as plain parchment for the scripture of the rappers, whose intricate flows syncopate with the steadfast groove and whose complex lyrics should be the focus of your attention, not the music.

All the rap records I collected over the 80s transformed into a big sample library in the early 90s. I definitely went out and bought even more “flat” hiphop in the 90s simply because I needed more breaks and vocal samples, not really for listening pleasure any more. But I did like the rawness of Wu-Tang and in 1993–94 I was hugely into the Dr Dre/Snoop sound.

After putting out a few more mid-tempo breaks tunes in the early 2000s, like “Dirty Raver”, you dropped out of music for about 15 years. You switched lanes completely, plunging into a career working in video, while also moving to Dubai. But then suddenly in the last couple of years, the Acen name has reappeared with tracks like “Play 2092” and “Thrilla” that build from the classic Acen sound of 1992. You’ve done a similar thing with your re-remixes and the totally new track “Rings Around The Moon” that appear on the Trip II The Moon 2092 box set. What’s it like trying to put on an earlier music self like an old pair of trainers?

I actually found it quite therapeutic to reinhabit the mindset of my 19 year old self and use the same methodology. The equipment was pretty much the same – I needed it to be authentic and so I hunted down the old Akai MPC60 and used a lot of the old methods of generating samples. Sometimes you need the old gear to trigger "that" sound and be inspired by that era.

The Guardian placed “Trip II the Moon” at number two in its list of All-Time Greatest Rave Anthems. Many old skool hardcore fans would place it at one. Casting modesty aside, do you agree? And what would its competition be?

Honestly, it’s impossible for me to really know what the biggest rave anthem was. Even for me personally, it was always a changing state of emotions: when a tune comes on at a particular moment and resonates with you, that is the biggest tune for you. At different times that would be The Prodigy’s “Your Love”, Genaside II’s “Narra Mine”, Nebula II’s “Athema”, Shades Of Rhythm’s “The Scientist”… Sound Corp’s “Dreamfinder” was another marvel.

You are obliged to be diplomatic, I’m sure, but which of the nine guest remixers does the best reinterpretation of “Trip” and its original B-sides “Obsessed” and “Life & Crimes Of A Ruffneck”?

If forced, I’d say that I was equally impressed with Pete Canon’s remix and NRG’s. But I have a soft spot for drum ’n’ bass and I also loved Danny Byrd’s take and the dark rattle of dBridge’s remix.

Trip To The Moon 2092 is released by Kniteforce. Read Simon Reynolds's review in The Wire 444

Leave a comment