Unleashing microtonality: an interview with Khyam Allami

January 2021

Khyam Allami photographed by Tim Dunk

The multi-instrumentalist and composer opens up a new world of microtonality with a pair of online compositional tools, and a season of concerts, talks and DIY sessions at CTM from 26 January

Born in Damascus to Iraqi parents and raised in London, Khyam Allami is a polymath – oud player and multi-instrumentalist, composer, founder of the label Nawa Recordings, and now software designer. He is currently completing a PhD in composition, and his research focuses on creating new works that explore Arabic music in novel contemporary and experimental ways. Leimma is a tool that lets users explore existing tunings, or create their own, which can be applied to Apotome, a sister application that allows a deeper exploration of tunings to create generative music. These applications are an attempt to highlight the cultural biases in electronic music-making tools, while offering a decolonised experience that allows users from any musical culture the freedom of a creative blank slate. Both applications were built in collaboration with Tero Parviainen and Samuel Diggins of Counterpoint, and are available online so that anyone can use them from a web browser window.

From 26–29 January, Allami is collaborating with CTM 2021: Transformation for a series of workshops, talks, and artist takeover concerts using Apotome – including collaborations with Deena Abdelwahed, Slikback, Lucy Railton and many others. He has also created tutorials for Leimma and Apotome, and users can contribute to a 24/7 Apotome live stream, running until 14 February. He spoke with Wire Deputy Editor Emily Bick about his work developing Apotome and Leimma, overcoming biases in tuning software, and what to look forward to at CTM.

Emily Bick: When did you first see that you needed a new kind of software solution for composition that would accommodate microtonality?

Khyam Allami: I guess the first time I noticed how much the software was impacting the kind of melodies I was hearing in my head, it was probably back in the very early 2000s. When I first started getting familiar with programming, it must have been Cubase back then, and Sibelius, I noticed that I would have a melody in my mind that I wanted to try and render, and then in relying on the playback from the softwares, the melody didn't feel quite right but it still sounded good. So I would follow that track and then very quickly I would end up somewhere very different from where I wanted to be.

One of the things you discuss in your essay, Microtonality And The Struggle For Fretlessness In The Digital Age, is that when you are actually composing on an instrument like the oud that's fretless, you can have that feedback directly. And you said that the software was forcing you to take mental paths that you wouldn't normally take, and music was being squelched by that.

Exactly. It wasn't until I started actually playing the oud, learning how to play and becoming a little bit more proficient, that I start to notice how much this was a limitation, and I got frustrated very quickly. That's why I decided to focus my energies on learning the instrument and becoming more proficient at it to develop that skill rather than banging my head against the wall with software, or at the time, you know. learning how to code and trying to develop something myself.

That was really the seed at the time and it was proposed by listening to a really great band called Secret Chiefs 3, Trey Spruance's band. Hearing what Trey was doing at the time really fascinated me because the feeling that I got from the melodies that I was hearing was very different to the feeling that I was getting from Arabic pop music from the 80s, 90s and onwards, which used digital synthesizers as well, and supposedly in Arabic tonalities, or in Arabic tunings. But what I was hearing from Secret Chiefs 3 was much more nuanced, and then I realised that actually that was the same feeling that I was hearing from the 70s Arabic recordings that were using analogue synthesizers at the time. Here the ball starts rolling, when you start to realise that there must be a connection.

I was disappointed with the fact that I couldn't use the software to develop ideas or feelings that I had. Before learning to play oud, I was playing drums and in metal bands and rock bands, I was frustrated, and got quite detached from electric music. The noise and generally the feeling of restriction – it's extremely difficult to make playing loud music your livelihood because you need so much in order to be able to do anything. Being a drummer, for example, you need your own drum kit, which means you need a car, which means you need to rent spaces and you need to lug things around and set things up. It was extremely draining to do anything that required volume. You need to go to faraway places where you're not disturbing people, and I just wanted something that I could feel and deal with in a very immediate and intuitive way. The oud really opened up that for me.

Absolutely. One of the ironic things is that a lot of young bedroom producers who are making electronic music, what they really like about being able to work with composition software and DAWs, is that it's just on their screen or tablet right in front of them, and it's easily accessible. But at the same time, the tools are adding to the constraint that limits the palette and the texture of what they can do.

I mean, it's the same for me. I'm attracted to these tools because they offer a kind of creative freedom that you don't get when dealing with acoustic instruments or electric instruments. Everything has its pros and cons. The drive over the last few years to find these solutions has also been because I want to be able to use these tools to expand my creative desires. The fact that a young bedroom producer, wherever, can sit down and use these very simple tools, to create whatever kind of music he or she wants to create with a sense of freedom, is something that I in a way feel envious of, right? And that got me thinking about what am I longing for here. Am I longing for freedom in in the creative process or not? And it got me thinking a lot about what it actually means to be free, in a creative capacity. What does it mean? Does it mean Coltrane? Does it mean Einstürzende Neubauten? Does it mean The Melvins?

I realised quickly that one of the main elements in freedom for me equals choice. All of my previous thinking was frustration with trying to reach an end goal. I realised that it wasn't about reaching an end goal. It was actually about having the freedom to have no ideas whatsoever. I wanted to be able to wake up in the morning, have no idea what I'm doing and have a blank slate, you know, tabula rasa, upon which I could experiment. And for that blank slate to be suitable for me, it needed to be able to render these kinds of tonalities, the details of intonation. And so that envy then for the freedom that I heard other musicians working with started to turn into a desire to create something that would allow that to happen. You need to facilitate it.

You give a really good explanation in your essay about the backstories of both MIDI and equal temperament systems, and how they've been used. It seems like the default that we have with equal temperament as a default tuning system is based on an idea of how easy it would be to transpose sheet music. It's almost like there's a kind of formal technology limitation that was imposed from an earlier form of technology and communication that's carried over into a point where now it's not necessary, but it's still just assumed as a default.

What was really eye-opening to read was when you were discussing how MIDI has been able to support something like 200,000 parts of an octave from the MIDI tuning standard from 1992. So the capacity for microtonality is there in MIDI, but we have these hidebound software and hardware systems that haven’t seen it be adopted more widely. And that just seems really shocking.

Yeah, it is! You know, I was just rereading a Wendy Carlos article from 1987 in Computer Music Magazine. This is two or three years after she had started developing her own software to experiment with other tuning systems. She released an album called Beauty And The Beast, which is a summary of her explorations. And to read that Wendy Carlos felt that this was a new dawn for music-making at the same time in which everything became so constricted, it feels as if the entire music technology world literally slammed the door in her face. It's insane that 30 years on, here I am still trying to find solutions for the same problems. When in fact the solution, well, the groundwork for that solution has already been laid. What’s more infuriating is that in reality equal temperament has never really been employed by musicians. When a piano tuner sits to tune a piano, they tune pretty close to equal temperament, but it's never exactly equal temperament, and as music moved more into the use of digital instruments and workstations, digital based environments, this is where the problem began.

If you listen to jazz records from the 60s, 70s, there's a feeling about the melodies and the intonation of those records that is completely different to the feeling that you get when you listen to jazz records from the late 80s that were using all the digital synthesizers at the time. The same today if you go and see a jazz band using a real piano compared to a jazz band that is using one of those Nord electric pianos. The difference in feeling is unbelievable. Even if it's the same dissonant weird chords and complex musicological modulations and transpositions. There's a feeling about that that is not right. Obviously that is even more intense when it comes to pop music today with everybody being completely determined to tune the hell out of everything, but the problem is not the process of tuning something and getting it to feel a certain way. The problem is that everybody's tuning everything to equal temperament. They're not even tuning things to themselves. I get frustrated because everybody's always searching for new sounds in some way, but they get these new sounds and then they just use the same old chord progressions and the same old melody types and the same tuning all the time and it just feels like such a waste.

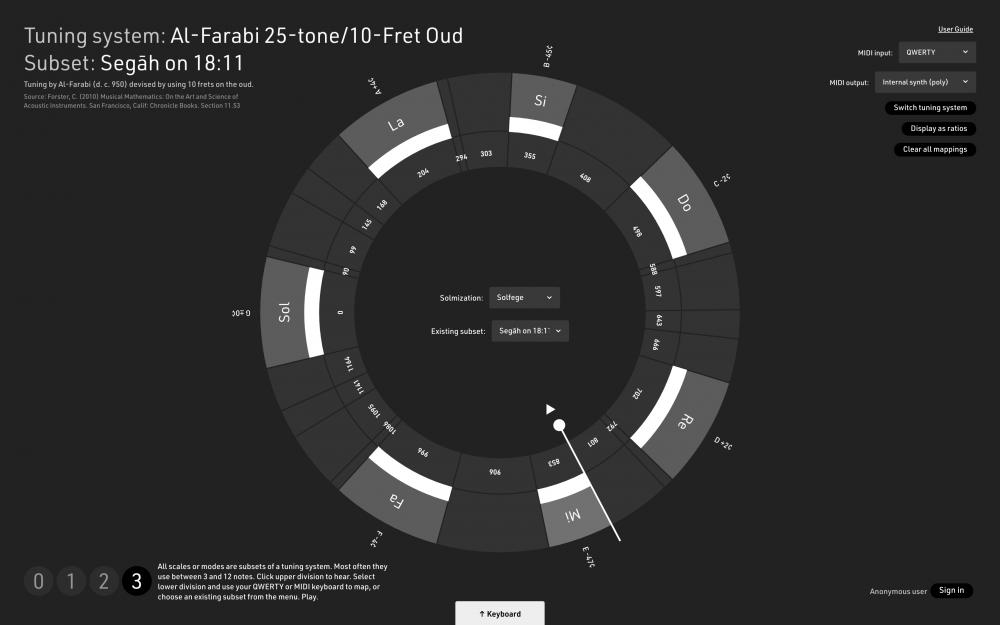

Leimma interface

Synth forums are full of really complicated patches and workarounds for alternate tuning settings. It's surprising that no one has filled this need really properly, with accessible tools.

The issue isn't to do with the technological capabilities of these devices. It's to do with the implementation by software and hardware manufacturers. And the software and hardware manufacturers that I've spoken to will always refer back to ‘Well, there is no market’. So there is an economic problem here as much as a political, social and creative problem. That somehow this particular aspect of music making is tied to the idea that only people from non-Western countries would need this, and those non-Western countries don't provide a market that's big enough to invest in making these kinds of capabilities easily accessible. This seems insane to me, that manufacturers who are at the forefront of creating new tools that redefine the sound of music, would consider it in that way.

But this comes down to the bias that's inherited. Which is the ‘Well, music is major minor scales, equal temperament and you know, the jazz variations and the Bach chorales and you know, whatever harmony and counterpoint based on these two hundred year old systems. And so that's it. That's all we need.’ There are so many people who have been pushing against that for many years, but they push against it by trying to find solutions that serve very specific end results. And always more or less from a Western perspective of what those end results should be. And this I guess is the primary difference of the way that I'm approaching things now, which is that I'm trying to take more of a non-Western perspective on things, and also reiterate this idea that subsets of tuning systems are equally as important as tuning systems themselves because that's when things start to become meaningful, but that's a longer discussion.

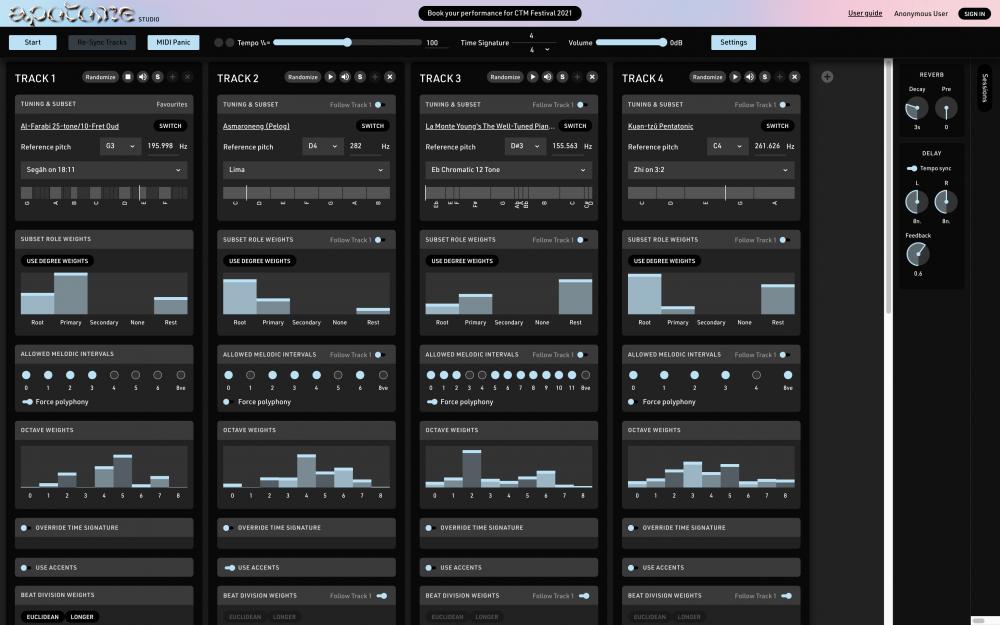

Apotome interface

Tell us about what you are doing with Apotome and Leimma at CTM. Did you do training sessions with the artists who you're going to be in concert with, so that they can learn how to use the software?

Yeah. Well, Jan Rohlf, one of the founders and directors and programmers of CTM, is a really wonderful mind. A very curious mind. We sat down together and brainstormed exciting musicians that we'd like to work with and we came up with a bunch of different ideas. As part of CTM, we have three preproduced artist takeovers by Deena Abdelwahed, Slikback and Wahono. I worked with each of them to different levels. With some of them. I worked very intensely, you know going through all the details of how Leimma and Apotome worked. Others were happy to pick it up on their own and run with it. So they have created preproduced live recordings in their own studios using Apotome with their own sound-making devices, whether that be hardware or software. That was really beautiful and super exciting. Slikback's recording is fascinating. He used only the software because he doesn't feel comfortable using hardware, and it's really phenomenal what he managed to pull out of it.

The other element that Jan was quite adamant about doing even though we have all of these restrictions is some kind of live show. So we decided that the live show would be Apotome sending out all of its data via MIDI to a group of synthesists. So that's going to be Tommi from Group A (Tot Onyx), Enyang Ha, Tyler Friedman and Nene H. They'll be playing different synthesizers, mostly modular synthesizers, and then Lucy Railton's going to be accompanying them on cello improvising all around.

I will be doing the first part of that where I'll be sending out the data from Apotome, so I'll be controlling the melodic and the rhythmic material, and they're going to be controlling the timbral, the sonic material. Then once I'm done with my set, Faten Kanaan will log onto my computer via remote access from New York, and she will manipulate her own session in Apotome through my computer which is sending the MIDI data out to the same musicians. So it's really live composition performance all together.

Then aside from those two, there's going to be a 24/7 live stream of Apotome generated music with a generative visual element that's going to be streamed via a website and inside CTM's Cyberia Festival environment. So you could create a little avatar and go in to Cyberia and wander around the festival site and go to the Apotome room and sit down to watch and listen to the generative music and visuals.

With Apotome and Leimma, you’ve deliberately made the tools browser based so you don’t need a lot of memory or hardware to use them, and both are open source – and you’ve invited users to create with them and contribute to the 24/7 stream at CTM. How do you hope these tools are taken up?

I need to put this out there with the plan to share as much knowledge as I can gather with as much energy and passion as I can, because that's the only way it's going to become useful. Then if there's any way it's going to become meaningful, you need to have accessible tools that look good, that feel good, that allow this creative freedom accompanied by very down to earth explanations. Workshop style materials that can help people break down all of these barriers. It is a complex subject that has engaged the minds of the greatest thinkers across time. This is a 4000 year old problem, it's not a 20th century one, but if the Chinese theorists from 1700 BCE could find such elegant solutions with just a few bamboo pipes, then I'm sure we can find incredibly elegant solutions with all the amount of coding that's at our disposal today.

The full programme of CTM events with Khyam Allami and Apotome can be found at the CTM website. Subscribers can read a Clive Bell profile of Khyam Allami in The Wire 379 (September 2015) on the online archive.

Leave a comment