From The Archive by Frances Morgan

September 2023

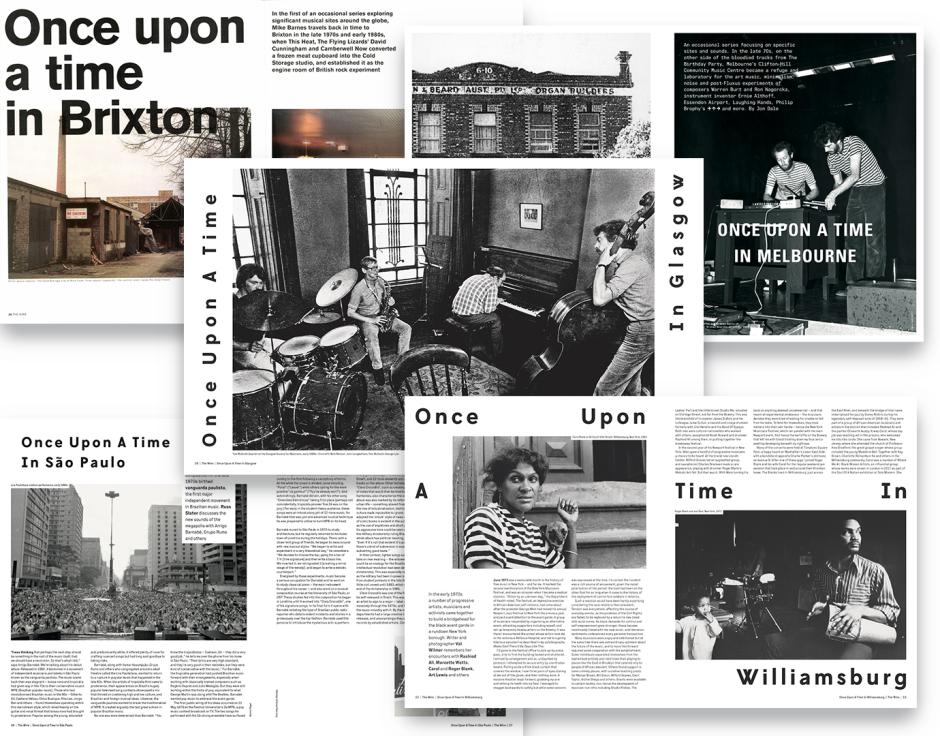

Clockwise to centre from top left: Once Upon A Time In Brixton in The Wire 258; Once Upon A Time In Melbourne in The Wire 272; Once Upon A Time In Williamsburg in The Wire 436; Once Upon A Time In São Paulo in The Wire 406; Once Upon A Time In Glasgow in The Wire 430

Contributor Frances Morgan compiles an annotated list of some of The Wire's Once Upon A Time In... special features that tell the stories of significant and localised scenes in underground music history. All selected articles are available to read in The Wire’s digital library with a print or digital subscription.

Since 2005, The Wire has run a semi-regular series of features exploring the connections between music and the places it’s made in. Rather than reporting on what’s happening right now in a particular location, the Once Upon A Time In… series focuses on key moments and movements in underground music history, and asks why and how they developed where they did.

Some of these features zone in on a specific building or street, and others take a more expansive view, such as Jacob Arnold’s piece on early-2000s IDM and breakcore in the Midwest (The Wire 405), which ranges between Chicago and Milwaukee (taking in record stores, home studios, dive bars and repurposed farm buildings). Others use location as a way into talking about a specific artist: Rob Young’s 2007 article on Egyptian composer Halim El-Dabh places him in the context of 1940s Cairo to tell a story about modernist composition, ancient ritual music and new recording technologies (The Wire 277).

I’ve chosen seven Once Upon A Time In… features in which a building is the catalyst for musical invention. It’s not a coincidence that many of the venues and studios described below were founded in the 1970s and early 80s, when deindustrialisation and lack of investment in inner cities left buildings empty and cheap, if not free, to occupy. As Val Wilmer notes in her account of free jazz musicians in Williamsburg, the next step is usually gentrification of formerly marginal neighbourhoods, and perhaps I’m drawn to these stories of grassroots spaces because it seems harder than ever to sustain radical centres for music and art in major cities now. But these brief histories are also a reminder that, however temporary a space might be, it has an impact on everyone who passes through it.

None of these features aims to be a definitive portrait of a place or time. The Brixton where This Heat’s Cold Storage studio was founded was also home to other scenes, happening in parallel; and there are multiple overlapping musical histories of São Paulo, Brazil’s most populous and diverse city, that could be written. But I think this is why the format works so well – because it’s essentially cumulative, each new instalment adding to what we know about underground music’s past.

Jacob Arnold observes that, “A surprising portion of the electronica scene from the early internet era is now lost to history, with URLs taken over by cyber-squatters and spammers”. This throws down a challenge to those documenting more recent scenes, not just because they exist online as well as in clubs and studios, but also because the artefacts get harder to access – as anyone in possession of boxes of unplayable minidiscs and CD-Rs, not to mention old hard drives and digital cameras, will know. But it would be great to see more Once Upon A Time In… features tackling the 21st century, now that we’re some years into it, because music will never not be informed by the spaces in which it’s produced.

Once Upon A Time In Brixton by Mike Barnes, The Wire 258 (August 2005)

The first Once Upon a Time In… article went deep inside Cold Storage, a studio unit in a former meat pie factory on Acre Lane, Brixton. Run by Acme Studios, which still operates as a provider of artists’ spaces, in 1977 the unit became the base for This Heat, as well as hosting other South London experimentalists including Art Bears, Test Department and, after the demise of This Heat, Charles Hayward’s Camberwell Now. Mike Barnes charts Cold Storage’s journey from a metal-walled cavern (Hayward remembers, “we got the lights on and realised there was blood in the dust”) to its brief existence as commercial recording studio in the 1980s. Having a configurable blank canvas of a space, not to mention round-the-clock access to recording equipment, enabled the hours of collective improvisation and tape experiments from which This Heat’s compositions were created. Hayward and producer David Cunningham attest to the importance of Cold Storage’s physical properties to This Heat’s sound, describing how sessions for This Heat and Deceit involved binaural mics, milk bottles rolling around the floor and field recordings of the neighbouring school (Cunningham’s Flying Lizards also recorded their hit single “Money (That’s What I Want)” there).

Once Upon A Time In San Francisco by Edwin Pouncey, The Wire 265 (March 2006)

I didn’t think I was that interested in Quicksilver Messenger Service, but the second paragraph of Edwin Pouncey’s feature on the rise of San Francisco’s psychedelic venues got me hooked: “[Chet] Helms approached a commune in Pine Street which had made a substantial amount of money through panhandling and were keen to invest their capital in a lucrative project. Their first idea was to run a pet cemetery called The Family Dog, but when they saw the potential of Helms’s basement rock jams they decided to enter the rock ’n’ roll business.” It’s a premise worthy of Joan Didion. Ostensibly an account of the early years of the psychedelic rock band formed in 1965 by John Cipollina, Greg Elmore and Gary Duncan, Pouncey’s article is also the story of the rise of a new kind of live rock venue – former ballrooms and dancehalls that required bands to push their sound to the limit, formalising distortion as a key ingredient in the psychedelic experience. As Duncan remarks, “the PA systems were nothing like they are now and the only way you could fill a space that size was to turn everything up.” A great example of how space and technology (and its limitations) help to shape musical genres.

Once Upon A Time In Melbourne by Jon Dale, The Wire 272 (October 2006)

Jon Dale’s history of the Clifton Hill Community Music Centre opens with an evocative photograph of former church-organ factory in which it was housed, and a description of a gig by Essendon Airport, the duo of David Chesworth and Robert Goodge: “Bubblegum pop meets process music; toy instruments and consumer electronics; breaking down the walls of the traditional performance space.” The Melbourne music and arts venue was set up in 1976 by composers Warren Burt and Ron Nagorcka, comprising a performance space and a larger room for multimedia installations – a photo shows a tantalising detail from Ros Bandt’s large-scale Coathanger Event. Dale’s article documents how, after Chesworth took over as co-ordinator in 1978, CHCMC became a centre for members of Melbourne’s post-punk (aka ‘Little Bands’) underground who eschewed the rock stylings of The Birthday Party and saw themselves as performing “a thoroughgoing critique of rock music and its received wisdoms”, including Wire contributor Philip Brophy’s group . Dale rises above a discussion of scene politics to show how CHCMC channelled this spirit of inquiry not just into live music but in writing, too, with Brophy and Chesworth publishing New Music magazine and releasing recordings on their Innocent label. “The music, thinking and writing that circulated around the centre simultaneously addressed meta-musical concerns about the place of art and the artist within politics and ideology,” he writes.

Once Upon A Time In São Paulo by Russ Slater, The Wire 406 (December 2017)

Russ Slater’s feature about independent music in early-1980s São Paulo leaves you wanting to know more about the Lira Paulistana. The theatre and arts centre, set up in 1979 in São Paulo’s university district, became an important location for the vanguarda paulista. This new wave of musicians and groups combined political commentary, serialism, pop, theatre and spoken word to shake up a Brazilian music scene that they felt had become staid in the decade since the forward leap of tropicália. Slater focuses on Arrigo Barnabé, who put out the first independent release in Brazil in 1980 (the Residents-ish Clara Crocodilo); Itamar Assumpção and his group Isca De Policia (Police Bait); and performance/theatre collective Grupo Rumo.

Lira Paulistana provided a space for gigs and meetings but also, writes Slater, “expanded into a bookshop and publisher and also presented festivals and outdoor events showcasing emerging artists.” It launched a record label, too, releasing 17 albums in total before closing its doors in 1986. Slater suggests that the vanguarda’s influence can be seen in today’s São Paulo, in which there’s a “highly independent music scene where the musicians own the rights to their own recordings and where they dictate their own marketing strategies.”

Once Upon A Time In Glasgow by Stewart Smith, The Wire 430 (2019)

“The story of British free music extends beyond England”, asserts Stewart Smith in this history of Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre (now the CCA), a venue for jazz and improvised music set up in 1975 by promoter, poet, dramatist and pianist Tom McGrath, who was, at the time, the Glasgow director of the Scottish Arts Council. Smith’s article is in part a portrait of McGrath, documenting his background on the London poetry scene and as a promoter for The Cell, a Glasgow jazz club, in the early 1960s, but also shines a light on important local musicians such as drummer Nick Weston and bassist George Lyle. There’s the sense of a genuinely exciting archive find, as Smith uncovers a trove of videos showing Derek Bailey, Julius Eastman, and Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath performing at the Third Eye (these and other videos shot by Tom McGrath and other Third Eye musicians and artists can be viewed here. Smith also delves into the archives of improvised music collective/booking agency Platform, which promoted local acts as well as hosting concerts by Art Pepper and Mahavishnu Orchestra, among others. In histories of local music scenes, bookers and promoters aren’t always give the credit they deserve. Smith’s article shows how important they can be.

Once Upon A Time In Williamsburg by Val Wilmer, The Wire 436 (June 2020)

In her book As Serious As Your Life, Val Wilmer describes a former shopfront on Broadway, Williamsburg, as a ‘legendary musicians’ commune’, where Rashied Ali, Roger Blank, Art ‘Shaki’ Lewis and numerous other musicians met, rehearsed and, in many cases, lived for a time. In this article she takes us inside 107-109 Broadway, describing how Ali renovated the building. After that property was destroyed in a fire, Blank, Lewis and painter Ellsworth Ausby set up a new communal space at 37-39, which Wilmer first visited in 1973. Her account of this visit is illustrated by intimate photographs of Roger Blank and bassist Hakim Jami with their young children, and a striking image of Carol Blank, Roger’s wife, an artist and member of Where We At: Black Women Artists (WWA), a collective that included Faith Ringgold, Charlotte Kâ and Kay Brown. In time, Williamsburg became “a destination for white artists, then for tourists, and eventually, a conglomeration of loft dwellers, renters, developers and homeowners”, but Wilmer ends her article on a hopeful note, pointing out that the Williamsburg Music Center, set up by Gerry Eastman in 1981, continued the legacy of those early pioneers by hosting concerts and exhibitions including a 2004 show curated by Carol Blank. The fertile relationship between music and visual art during this period is an underlying theme in Wilmer’s piece, and it left me determined to find out more about WWA.

Once Upon A Time In Maida Vale by Nick Soulsby, The Wire 474 (August 2023)

A Spanish community centre housed in a dilapidated Victorian school building on the Harrow Road is the location around which Nick Soulsby bases this story of how urban space, underground music and radical politics intersect. Founded in 1970 by Miguel JM García García, a Spanish anarchist exiled from his home country during the Francoist dictatorship, the original Centro Iberico was in Central London, moving north a few years later and then west to Maida Vale. From the late 1970s to 1981, when residents were evicted, older Spanish activists shared the building with squatters, and the old school hall played host to Throbbing Gristle, Crass, Rudimentary Peni and other industrial and anarcho-punk groups. Initially, political activism and music co-existed: benefit gigs were put on for anarchists arrested in police raids, and the centre hosted a three-day anarcho-feminist conference. But while Soulsby’s article celebrates the collective spirit of the Centro Iberico, he doesn’t shy away from conflicts that arose between musical and political factions, citing a flyer that circulated around the venue: “those who need to fall back upon a set of lyrics or painted leather jackets to prop themselves up will not survive… those who are willing to challenge the state… these are the ones who can earn the right to call themselves anarchist.” Nonetheless, Null & Void member Mark Hedge recalls the space as “a meeting of tribes: tribes of misfits, tribes of people failed by the education system and by the state.”

Join The Wire’s online library today to read all these articles and gain access to the entire archive of back issues dating back to 1982. Print subscriptions also include library membership: thewire.co.uk/shop

Leave a comment