Ian Penman

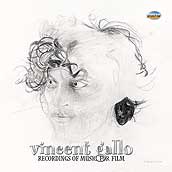

Vincent Gallo: Recordings Of Music For Films

An archive of flickers and ghosts and weather probes, each track a different exploration of instrumental tone and texture. This review originally appeared in The Wire 220 (June 2002).

VINCENT GALLO

RECORDINGS OF MUSIC FOR FILMS

WARP 96 CD

Note that strictly utile title. Here we find not vanity project Muzak for 'imaginary' films, projected by some vain musclehead Hollyweird jerk-off with more friends than talent, more contacts than kudos, more photo spread profile nous than musical knowledge. There is nothing imaginary about Vincent Gallo. Still, with Gallo it's hard to disentangle myth from mystification, hubris from humour. Is he the borderline homophobe/ultra-conservative who tells a gullible style magazine that his all-time heroes are Yes bassist Chris Squire and ex-No man Richard Nixon? Or is he the earnest psychogeographer of forgotten LA independents who worships Kenneth Anger? Gallo seems to tell gullible - and powerful - interviewers exactly what they don't want to hear, on any given occasion. Which, the way things are right now, is something of a relief. We need new dreamers. And this is an archive of dreams.

Last year's When (also on Warp, which says something about Gallo's take on things: former Sheffield Techno outpost rather than Geffen guestlist goldpot) turned out to be one of my favourite CDs of 2001. "All music written, performed & produced by Vincent Gallo." Put together at "The University for the Development and Theory of Magnetic Tape-recorded Music Studios"; which turns out to be Gallo's Hollywood home, but in effect is Gallospeak for Gallo's own head: the dreamspace he has marked out. The way he thinks things should be: if you love something, then do it with love. Love under will. Before he can record, he must build his own recording studio. The man is a tape delay alchemist (currently, he has the beard to match).

If you go to his Website for a peek inside the man's super ego, you'll be warned off sending fan mail - he doesn't need you to tell him he's a genius; he doesn't need you to take precious time away from the daily task of being a genius, of being sui generis. But what you will find is a wish list of old analogue equipment: an obsessive attention to detailed knowledge of... getting it right. Materialising this... sound in his head. And this wish list, it's not just flash axes, Telecaster ghosts haunting some plectrum bore who listened to too much Zappa as a nerdy kid. Gallo is fixated on microphones, cables, synths, recording equipment. Magical tools. Things to capture the aether... just so.

There is also glamour, which some (envious of his batting average?) find off-putting. The opening track on When, "i wrote this song for the girl paris hilton", could be off-putting if you know this 'girl' is something like the US society equivalent of Tara Palmer Tompkinson. But the 'song' - a spacey instrumental - is a little patch of fascination, a sleepwalk pulse; and five of When's tracks are likewise instrumental. Texture is his thing; oblique dreams of lost analogue transcription. Making concrete the indefinable: mood, longing, how you remember how things sounded that time. The key to When is that you can listen to it purely for textures alone, before focusing on any of the diaristic lyrics, delivered in Gallo's uncanny fix on blue afternoon/dark LA croon (Tim Buckley, Chet Baker). Where most macho actors want to be boogie rawk bores, Gallo wants to be something like the male Björk. A comparison I'm sure he would execrate.

However: we shouldn't forget he's an actor - not to mention an accomplished (to say the least) liar or fabulist or mythomane, as anyone who's read his interviews will confirm. But the thing is... it all turns out to be true. He did do 'x'. He was 'y' 20 years before anyone else. He can, he will, he does.

Some dim reviewers appear to have dismissed When purely on their dislike of the Gallo vibe, just as Paul Schrader reportedly wouldn't even consider Buffalo 66 for any kind of inaugural Sundance prize, purely on his disaffection for the young auteur: which is inane. You don't have to like him: but you have to admire the fact that he DOES what he SAYS. While all around him, culture turns into a con game of image and interview, PR and preening, he goes against the spirit of an age in which stars are celebrated for their emptiness and promises are made to be spoken but not followed through on. You get the impression he'd be doing all this anyway, and doing it his way, if his only audience was the girlfriend du jour. Or just his own conscience, and conscientious aesthetic.

Recordings For... is both harder to access than When (more difficult, diffuse, dozens of moods rather than one, only one vocal track) but it will also be harder to dismiss. He's way ahead of the game - and, here's the thing, has been for years. These recordings represent nearly 20 years of lo-fi hi-ambition work: from his very first short film, If You Feel Froggy, Jump, in 1979, to Buffalo 66 in 1998. There are 29 tracks. An hour plus. This is an archive of real work.

29 tracks and barely a repetition. Capsule summary? Think the Eno of Another Green World, except less sleek, not so coy, sieved through the more recent klang and crust of Indie USA: Sonic Youth, Royal Trux B sides, latterday Fahey. He avoids the obvious: his sense of outsider 'adventure' closer to some lost 1970s Incus release than any Red Hot Chilli Popper. This is an archive of flickers and ghosts and weather probes, each track a different exploration of instrumental tone and texture. He can do Django gliss; he can do feedback ache. He can do Industrial hum. Little dark polaroids of gnomic memory music. Is that portrait completed with a zither? Is that distant beat vaguely Native American? Gallo is like Ry Cooder on a tattered baseball shoe budgetŠ but with Gallo playing all the parts, rather than importing some octogenarian Spanish guitarist, or blowing the budget on a sunnyday field recording. The often ragged, murky, basement taped quality makes for quietly gripping sonic relief - with no unnecessary flash, or undue flourishes, just prickly clips, gnarly cuttings, splices and immersions. (Sometimes the recording hiss is louder than the squeaks, squonks and guitar caresses.) Its aggrieved melancholy is set out with such palette and patience it transmutes into a kind of desperate affirmation. (Fail. Fail better. Love. Love more. Lose. Lose more.) "I Think The Sun Is Coming Out Now": his final word. Maybe, just maybe, he is everything he says he is: desperately sincere.

This is an archive of almost forgotten dreams, with Gallo as his own Harry Smith. This is an archive of surprises. And one of the surprises of the year.

Comments

The music gallo!!

Henry

ian penman's writing is very adequate for gallo's music. a beautiful text for a beautiful album.

Leave a comment