Read an extract from Too Much Too Young: The 2 Tone Records Story by Daniel Rachel

January 2024

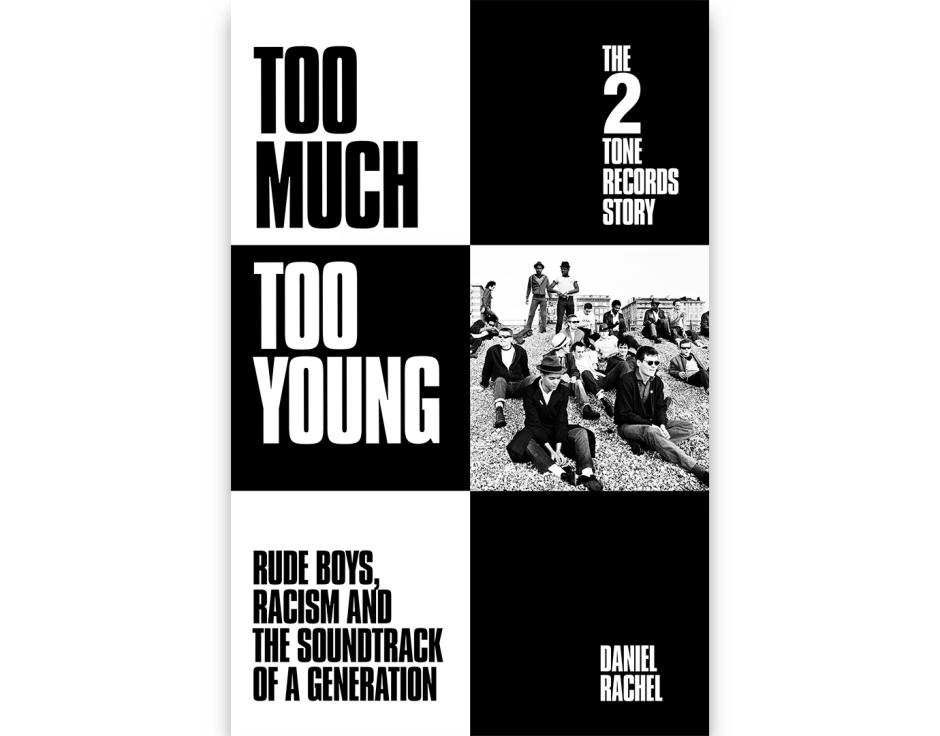

Front cover of Daniel Rachel's Too Much Too Young

Rachel's exploration into Jerry Dammers's 2 Tone label explains how punk reggae evolved to become the “soundtrack of a generation”

Chapter 3: Bluebeat Attack

Punk and reggae. Rock Against Racism. Coventry Automatics

As a genre, punk had little if any trace of Black musical influence. Where punk was unrestrained, often rejecting melody and musical proficiency in favour of attitude and spirit, reggae relaxed the heart rate, pumping deep drum and bass grooves to stir the soul and shake down aggression. Punk and reggae appeared to be diametrically opposed to one another. Then, in 1977, everything changed. First The Clash. Then The Ruts, The Members, The Police and a host of white musicians began to incorporate reggae rhythms into straight-laced English grooves. The Clash introduced a cover version of Junior Murvin’s “Police And Thieves” into their set, recorded with the legendary Jamaican producer Lee Perry, and as the ‘(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais’ declared a bluebeat attack, a generation of white youth discovered a hypnotic reggae groove. It was a welcome balm to the high-octane energy of punk rock and, significantly, brought to the stage what many were experiencing at blues parties and enlightened clubs. ‘It was bound to happen one way or the other,’ suggests Jerry Dammers, ‘because that was the music we grew up with, that inspired us. Punk and reggae are very separate kinds of music; and although it embraced reggae, punk was a separatist movement and very much white. For me, reggae made punk gigs bearable. The lyrics may have been good, but the music was more or less unlistenable. To actually sit down and listen to a Sex Pistols LP... I mean, who’d do that? It gave me a headache. I wanted to create a more mixed atmosphere.’

And yet, smouldering beneath the surface of the unlikely alliance between Black and white youth was an increasing undercurrent of hatred and resentment. As a country respected for its racial tolerance, England looked challenged. Ideologically opposed to racial integration, the National Front, and other similar right-wing groups, had increasingly gained electoral support throughout the 1970s. Advocating voluntary repatriation of all non-white, English-born citizens, the National Front rallied to slogans like ‘Keep Britain White’ and ‘The Red, White and Blue Swastika’, and spoke of Adolf Hitler showing ‘a proper, fair and final solution to the Jewish question.’ Its leaders shared photographs of themselves attired in Nazi regalia. By 1979, the National Front was finishing third at the ballot box and pledged to field candidates in all 635 constituencies at the next general election, guaranteeing the right to a party political broadcast on national television.

Matching their political aspiration, the National Front organised marches through immigrant-populated towns and cities, inciting fear and violence. This increase in racial tension coupled with established rock stars, such as Rod Stewart, Eric Clapton and David Bowie, and punk rock leaders like Johnny Rotten and Siouxsie Sioux, flirting with Nazi rhetoric and imagery. Whether the engagement was ideological or merely fashion at play, it was sufficient to trigger the formation of Rock Against Racism, and thereafter the Anti-Nazi League.

In August 1976, Eric Clapton made a series of obscene racist comments at a concert in Birmingham, spouting ugly denunciations of ‘foreigners’ who should ‘go back home’, that

‘England was a white country in danger of becoming a colony within ten years’, and that ‘we should all vote for Enoch Powell’, whose infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech incited white nationalism. Witness to Clapton’s diatribe from the front-row stalls, Dave Wakeling, lead singer of The Beat, says, ‘Then there was a lot of saying “wogs” and “get ’em out”. It was typical to hear people saying “wog” but not from somebody on the stage and certainly not from someone playing a Bob Marley song [“I Shot The Sheriff”]. All you could hear was, “What a bleeding nerve!” I wrote a letter to the NME. But it turned out there were loads of letters that said more or less the same thing. I was pissed off because most of them hadn’t been there.’

Red Saunders, a left-wing activist who called for ‘a rank-and-file movement against the racist poison in rock music’ and the formation of Rock Against Racism (RAR), wrote one such letter of disgust. The response was instant. Correspondence poured in from all corners of the country. Acting quickly, RAR organised gigs billing white (punk) groups with Black (reggae) acts. Then, at the end of the evening, musicians came together to ‘jam’ as a political statement and a visual symbol of racial unity. Inspired by Rock Against Racism, Jerry Dammers envisioned forming a multiracial punk reggae band with both Black and white musicians. ‘It was a subtle but important difference,’ he says.

In July 1977, Jerry recruited bass player Horace Panter, a middle-class art student from the sleepy market town of Kettering, Northamptonshire. Panter had arrived in Coventry to a stark warning: ‘The chap in charge of the halls said, “Be careful when you go out at night because people get murdered.”’ Finding relative safety in a college group and then a local soul and funk combo, Panter recalls meeting Jerry for the first time. ‘He was this strange mod character with sideburns and tartan trousers, who whistled skinhead reggae and pounded out Fats Domino and boogie-woogie on the pub piano.’

Continuing his quest, Jerry enlisted, or more accurately pilfered, a clutch of local musicians to complete the inaugural line-up of The Specials. ‘We started rehearsals at the Heath Hotel,’ says Neol Davies. ‘I went for a few weeks, but it soon became apparent that Jerry and I being in the same band wasn’t going to work.’ One day, Neol arrived at rehearsals only to discover Lynval Golding playing guitar in an authentic trebly reggae style: ‘Oh, I understand,’ Neol spat out. ‘See ya.’

Too Much Too Young by Daniel Rachel is published by White Rabbit. Read Neil Kulkarni's review of the book in The Wire 479/480. Wire subscribers can also find the review online in the digital library.

Leave a comment