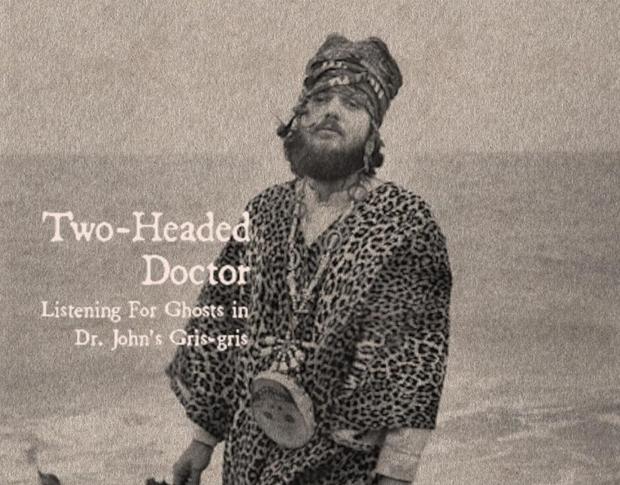

Read an extract from Two-Headed Doctor by David Toop

September 2024

In an exclusive extract from his new book, Two-Headed Doctor: Listening For Ghosts In Dr John’s Gris-Gris, David Toop follows anthropologist turned writer Zora Neale Hurston into the New Orleans of the late 1920s to sample the beliefs, tall tales and magical workings that comprise the mythopoetic substance of Dr John’s peculiar character and sound

Two heads are better than one

“It was difficult to make out all the words he sang. Some notes barely left the gravel depth of his throat or came forth over his humming; they were clear only when his voice came to a shout.”

Peter Everett, Bellocq’s Women.

“We had a different sound from other duos,” wrote Cher, “because I would sing the low melody and Sonny would take the high harmony, the opposite of what everyone else did.” Early on during the period of working on Sonny & Cher sessions, [Dr John aka Mac] Rebennack offered Cher a song he had written but Bono vetoed the idea. He was a controlling man, not about to give a sideman some leverage, but Rebennack took it personally. “I think [Sonny Bono] always feared that she would show him up too bad with singing, ’cause he knew he can’t sing,” he told Charlie Gillett. “If it hadn’t been for him I’d never have got out there to sing. Sonny gave me the courage to sing, man. When I heard him and Bob Dylan, between the two of them, I realised you didn’t have to actually sing. As long as you could project the lyrics across you could get songs out there.”

At the point of recording Gris-gris in 1967 he had hardly sung on record. Most of what he recorded up to that point was either an instrumental or fronted by a singer. Suddenly a voice had to be found, or fashioned. “I pitch it painting a picture not only of voodoo but of myself as a dismembered thing,” he said. “Instead of using my regular, natural voice, I whispered – hhe-be-be-be – used that thing, not only to make it mysterious and eerie but to make it so I could come back and be myself at some other point.”

This notion of dismemberment is interesting for its similarity with a shamanic trope, the process of initiatory sickness, visions, ecstasies and dreams of dismemberment, part of the calling to shamanism which leads to a death of the old identity, then from death to rebirth through instruction and reassembly. To cut apart the body, whether in Tantric practice or shamanism, was to break down the idea of fixed identity. Mircea Eliade collected many examples for his classic work, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques Of Ecstasy. There was the Siberian Yakut shaman who lies in a yurt for three days without eating or drinking: “The candidate’s limbs are removed and disjointed with an iron hook; the bones are cleaned, the flesh scraped, the body fluids thrown away, and the eyes torn from their sockets. After this operation all the bones are gathered up and fastened together with iron.” Then there was the Teleut woman who became a shaman after unknown men cut her body to bits and cooked it in a pot, or the Araucanian shamanic ceremonies of Chile and Argentina, where “the masters and neophytes walk barefoot on fire without burning themselves and without their clothes catching fire. They were also seen to tear off their noses or tear out their eyes.” Part of this rite of passage might include the acquisition of a new voice, as with a complex narrative collected by the Soviet ethnographer AA Popov in which the initiate has his heart torn out and thrown into a pot, meets the Lord of Madness and the Lords of all the nervous disorders as well as the evil shamans, then journeys with his guide to the land of female shamans, who strengthen his throat and voice.

Voice of the muddy monster

“Believe” by Cher, released in 1998, was the first recording to push the settings on Auto-Tune vocal pitch correction software to extremes, transforming what was intended as a utility into a device that could mask the voice or transform a vocalist into a hybrid human/android being. The sound was so distinctive that it became known as the ‘Cher effect,’ destined to radically alter pop music vocals for the next 20 years and more.

A mask is not necessarily a physical object. Some masks are too powerful to be worn; some artefacts disguise the voice in various ways, by distortion, buzzing, muffling, but the transformed voice of a hidden person is the mask, not the physical device. A voice mask can also be produced by a sound that is not a voice. “The appearance of African masks, above all the face mask,” Hugo Zemp wrote in his notes to the Ocora LP, Masques Dan: Côte D’Ivoire, “is well known all over the world thanks to collections and books on African art; but their voices are much less familiar. The voice is, nevertheless, an essential part of the performance when the mask appears. True, mute masks exist; but there are others which are exclusively sound masks, ie they assume no visual disguise.”

From his 1960s fieldwork and recordings of mask rituals performed by the Dan people, a Mande ethnic group of Ivory Coast and Liberia, Zemp found three methods of masking: “Since the masks (gué) are considered by the Dan as supernatural beings, they obviously neither speak nor sing with a human voice. But since they are incarnated by men, the men must change their voices into the voices of supernatural beings. The Dan have three ways of doing this – they distort their own voice, speak into an instrument which changes the quality of their voice, or replace the human voice by sound instruments hidden from the uninitiated.” As examples of the latter type, the Guéwova, ‘Mask with the Big Voice’ is the ominous droning of two whirled bullroarers; Guémano, ‘Little Bird Mask’ is the whistling of a whirled slit cylinder; and Guéyibeu, ‘Mask that Eats Water’ is an earth drum, a pit covered over with bark. Vegetable fibres are attached to the bark and these are abraded by two men who rub the fibres between their hands. A third man pours water on the fibres to enhance the sound, hence the name of the mask, water eater. Simultaneous with these remarkable sounds, an undisguised man shouts to his assistant, voice roughened and guttural. The timbral composite is unearthly, freely structured and repetitious as if to represent the raging, roaming presence of a non-human entity.

In 1968, ethnomusicologist Pierre Sallée recorded an equally remarkable and even more disembodied example of vocal masking during his fieldwork in Gabon. While documenting the ancestral Bwiti ritual of the Mitsogo people, during which psychotropic bitter roots and bark of the Tabernanthe iboga shrub are consumed by initiates, Sallée encountered the Voice of the Ya Mweï, Mother of the floods, a tutelary spirit with the ominous reputation of muddy monster, “who keeps order by threatening to ‘swallow’ those guilty of social transgressions, as it ‘swallows’ the dead. It is by this spirit’s name that oaths are sworn.” The hoarse voice of the muddy monster is produced by a hidden man, his pharynx inflamed by swallowing a brew made from the leaves of the tiliacea plant. At the conclusion of his enraged roaring and ruminative growls, a decisive drum beat is played three times, said by Sallée to represent the flicking noise of the monster’s tail. To wear a mask is to become two-headed, even though one of those heads may be invisible.

Two-headed doctors

“Now I was in New Orleans,” wrote Zora Neale Hurston in Mules And Men, “and I asked. They told me Algiers, the part of New Orleans that is across the river to the west. I went there and lived for four months and asked. I found women reading cards and doing mail order business in names and insinuations of well known factors in conjure. Nothing worth putting on paper. But they all claimed some knowledge and link with Marie Leveau.” Hurston had reached the last stage of an anthropological collecting trip that had begun in New York City on 14 December 1927, worked its way to Mobile, Alabama, down to Florida and finally to Louisiana, where she immersed herself, as was her practice, in lives, beliefs, circles of trust, stories, tall tales and workings of magic, then translated those and other experiences into the intensely vivid, personable, often drily comic prose of books such as Mules And Men and Tell My Horse: Voodoo And Life In Haiti And Jamaica. In 1925 she had enrolled as an undergraduate at Barnard College, the women’s college of Columbia University. She was the only Black student, Alabama born and already 34 years old. At first she majored in English but when advised to broaden her coursework, she signed up for a class with Gladys Reichard. A small but highly influential group of women emerged from the tutelage and mentoring of Franz Boas, the German born ethnographer who was attempting to put an end to so called scientific racism, eugenics and their deterministic racial hierarchies, to persuade people to think instead about culture as a non-linear web of wildly varying, mutable notions, traditions and behaviours that constitute ways of living as a connected individual within society.

Zora Neale Hurston, with permission from the Library of Congress

“The concept of race, Boas believed,” wrote Charles King in Gods Of The Upper Air, his study of this circle of anthropologists, “should be seen as a social reality, not a biological one – no different from the other deeply felt, human-made dividing lines, from caste to tribe to sect, that snake through societies around the world [...] The valuing of purity – an unsullied race, a chaste body, a nation that sprang fully formed from its ancestral soil – should give way to the view, validated by observation, that mixing is the natural state of the world.”

Among the women who graduated from or acted as researchers for Columbia University’s department of anthropology were: Gladys Reichard, who published her fieldwork among the Dine’ (Navajo) in books such as Prayer: The Compulsive Word, Spider Woman: A Story Of Navajo Weavers And Chanters and Navajo Religion; Ella Cara Deloria, of Dakota Sioux and European descent, writer of a beautiful posthumously published novel, Waterlily, which fictionalised the daily lives of a group of 19th century Sioux; Ruth Benedict, who used the model of Apollonian and Dionysian cultures in her influential book, Patterns Of Culture; Margaret Mead, who became the most celebrated of them all with Coming Of Age In Samoa; and Hurston, who wrote novels, investigative journalism, short stories, anthropology and folklore studies, as well as collaborating with sound recordists Alan Lomax and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle, researching potential connections between African-American songs and their originary sources in the music of Africa.

In New Orleans, Hurston wanted to know more about the 19th century voodoo queen, Marie Leveau (more commonly written Marie Laveau). Across the river in the Vieux-Carré, the French Quarter, she heard whispers of a hoodoo doctor, Luke Turner, said to be her nephew. At this point a confusion between voodoo and hoodoo becomes apparent. Hurston underlined an important distinction between the two in her essay entitled Hoodoo In America, published by The Journal Of American Folklore in 1931. In New Orleans Voodoo, Carol Ellis is succinct in her understanding of these two entwined spiritual practices: “Hoodoo is not synonymous with Voodoo, but they are closely related. As a religion, Voodoo involves the worship and honouring of spirits in nature. Hoodoo involves the use of herbs, roots, minerals, and other natural objects to draw on the power of those spirits and create changes in people’s lives.” The origins and overlapping of hoodoo and voodoo are complex, to be returned to later in this book. Hoodoo is also known as root work or conjure. “As in formal medicine,” Hurston wrote, “some of the doctors are general practitioners and some are specialists.” One doctor might specialise in court cases, another in repairing or breaking up relations with others; the many examples of conjurations and practical spells collected by Hurston in her essay shows the extent and variety of cases and the elaborate methods and ingredients through which they were said to be cured. But the practitioners inhabit two roles, indicating a holistic or integrated view of ailments and tribulations. “All of the hoodoo doctors have non-conjure cases,” wrote Hurston. “They prescribe folk medicine, ‘roots’, and are for this reason called ‘two-headed doctors’.”

Researcher Billy Middleton goes into greater detail in his essay, Two-Headed Medicine: Hoodoo Workers, Conjure Doctors, And Zora Neale Hurston. “In treating their patients,” he writes, “Hoodoo practitioners in the South were often referred to as ‘two-headed doctors’, underscoring the many dualistic elements of their identity: their ability to do both good and harm as dictated within Smith’s concept of pharmacosm [Theophus Smith’s portmanteau word fusing pharmacopeic and cosmos, referring to voodoo’s power to both heal and harm], their existence on the dividing line between religion and folk magic, their dual Christian and African religious roots, and their ability to both heal and practice divinatory magic [...] The term ‘two-headed doctor’ also recalls the bodily holism that characterises Voodoo religion and Hoodoo medicine.”

In the interviews compiled within his monumental five-volume work of oral history – Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork: Beliefs Accepted By Many Negroes And White Persons, These Being Orally Recorded Among Blacks And Whites – Harry Middleton Hyatt heard many stories of the two-headed doctors. One informant in New Orleans is described as a “doctor not accepting live-things-in-you cases”. Not considering himself competent to deal with a case in which a man had been rubbed with a salve made from earthworms and now had earthworms in his skin, he had taken the patient across the river to Algiers, to Pelican and 26th, for consultation with a woman named Madam Helen. “When you went into that room, did she have an altar in that room?” asked Hyatt. “She had an altar,” the informant replied. “It had a lot of candles burning – black candles, blue candles, purple candles, white candles, amongst diff’rent pictures [of saints] she had... She had on about three or four skirts. She dressed something like a gypsy woman do.” Another informant, a maid who worked for Madam Helen, described her as a “crackerjack”, a white woman who treated Black and white patients on different days of the week. “Well, she was a two-headed lady, see. Well so many peoples coming to her backwards and forwards [...] But she had a place – great many coloured go there, you know, they’d dance and carry on and everything. Well, she had a big house. She had snakes. She had any kind of animal you wanted to see around her house. If you was hurt or anything by any kind of animal and went to her to cure you, she would have that animal dust or grease or something to give you to cure you.”

Familiar with the work of Zora Neale Hurston and Newbell Niles Puckett (author of Folk Beliefs Of The Southern Negro) when he began to collect this material in 1936, Hyatt was acutely conscious that many white researchers preceding him had failed to understand their own insularity, the inhibiting and fear-inducing effect of their own whiteness. This was, of course, one of the reasons why Boas had encouraged Hurston’s folklore-collecting field trips to the South, and why Ella Cara Deloria understood that white researchers on the Sioux reservations would get nowhere with their questionnaires. She knew that knowledge of kinship terms, food offerings, sensitivity and the right tone of voice were prerequisites for her style of respectful, consensual anthropology. Hyatt knew he had to get out into the field and really listen. Sensitive to Black-white relations he would set up for recording informants in Black homes or downtown Black hotels, knowing that if you invited a Black person into a white home they would be unwilling to speak openly. A STRANGE WORLD is how he described it and wrote it, capitalised, in his introduction to the first volume: “For throughout the following pages, 1606 strange-world believers and I will talk about magic rites and spirits – talking on more than 3000 old-fashioned Ediphone and Telediphone cylinders [...] a serious investigation of superstition [...] journeys among people and into their minds.” In later life he regretted shaving many cylinders so that he could use them again. Worst still, he had destroyed them all. “The storage problem must have been immense,” wrote Michael Edward Bell in an essay for the Journal Of Folklore Institute, “with boxes and boxes of unwieldy, fragile cylinders. Since all of them had been transcribed and the transcriptions retained, Hyatt saw no reason to keep the original recordings. Now he refers to the act as ‘that great crime of mine’.” So the grainy voices of 1606 strange-world believers were lost, silting down into the great compost, worms under the skin.

Two-Headed Doctor is published by Strange Attractor. Read a review of the book by Michaelangelo Matos in The Wire 488. Wire subscribers can also read the review online via the digital library.

Leave a comment