Read an extract from Solid Foundation: An Oral History Of Reggae

December 2024

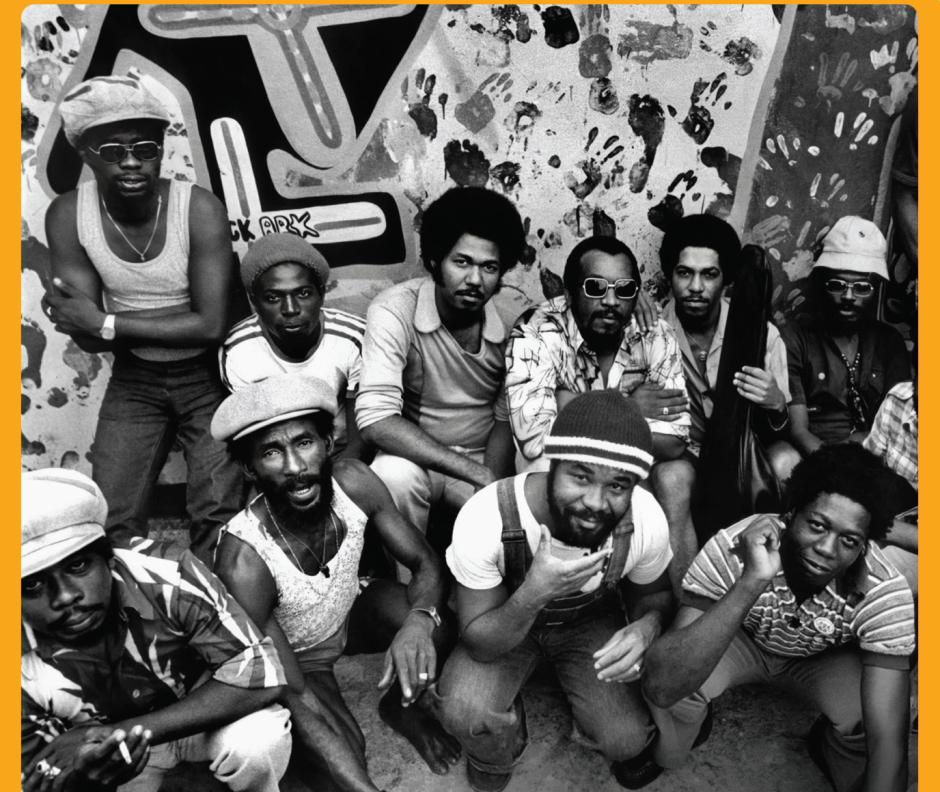

The front cover of Solid Foundation: An Oral History Of Reggae (crop)

In an extract from his new book, David Katz charts the emergence of Jamaica’s sound system culture in relation to social and political transformations that underpinned the country’s fight for independence

“The two first sound system clashes in Jamaica was between Tom the Great Sebastian and Count Nick in 1952. Tom beat Nick, and the return was up at Nick’s yard in Waltham Park Road – Tom beat him both times. Tom was great, man! Him friend send some big tune for him from New York and that night, if you see the crowd ...” – Duke Vin

“We do rhythm and blues songs – all Jamaican artists in those days try to do rhythm and blues.” – Skully Simms

Jamaica’s popular music has undergone a series of labyrinthine changes, a transformation that mirrors the island’s cultural and political growth. Born from the everyday struggles of the dispossessed in a seemingly peripheral island nation, reggae is infused with issues of identity and reactions to the centuries of colonialism that shaped modern Jamaican society. The music’s progression charts a complex course, shadowing the growing pains of a developing nation.

When Jamaica achieved independence from Britain in 1962, the island celebrated with ska, a uniquely Jamaican hybrid. Ska is intimately connected to the independence movement and was the first Jamaican style to attract significant foreign interest; because of this, it is often seen as the starting point of contemporary reggae. But in order to understand the emergence of ska, certain earlier strands of musical culture must be traced. The most important include Jamaican R&B (ska’s immediate predecessor), the thriving urban jazz scenes, the indigenous folk style called mento, and above all, the sound system culture that since the 1940s has been the perpetual arbiter of Jamaican musical taste.

As the inhabitants of the Isle of Springs all have ancestors from elsewhere, its popular culture has a wide range of influences. Although the British maintained the chief colonial presence for over 300 years, the music of Black America provided the strongest model for Jamaica’s urban musicians in the 1940s and 50s – perhaps not surprising, given its proximity. The USA continues to exercise the greatest industrial, financial and military power in the region, as well as cultural dominance, and until relatively recently, American radio and television programmes disproportionately filled Jamaican airwaves.

Although Black American music had the strongest influence in the postwar years, other forms were also noteworthy. The son and bolero styles of Cuba, sandwiched between Jamaica and the USA, were highly influential, as was the music of nearby nations such as Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Panama. But perhaps the most important elements came from the ancestral homeland: Jamaican slave descendants retained many more vestiges of African culture than their US counterparts. Sacred drumming techniques found in African-derived Pocomania church services involving spirit possession or accompanying Junkanoo masquerade dances further evolved from the backbone of Jamaica’s folk music and ultimately became defining elements of reggae. Other important folk elements developed during slavery days include the call-and-response chants of work songs and children’s ring games, and the adaptation of 19th century European dance music known as quadrille.

The fife and drum of quadrille was a notable influence on mento, a style from the Jamaican countryside that has similarities to the calypso of other islands, but which is distinct, due to unique instrumentation. In the 1940s, increased migration to Kingston brought mento bands with it. These groups of roving troubadours gave informal street performances offering social commentary and satirising current events. The bands typically featured hand drums, banjo, and the oversized kalimba or ‘rumba box’ (a distant relative of the mbira, used for bass), often with a fife or penny whistle, and perhaps a bamboo saxophone. From the early 1950s, mento groups were regular features on the north coast hotel circuit.

Among the savvier city dwellers, jazz held greater currency. Since at least the 1920s there was a thriving Jamaican jazz scene, and in the economically buoyant postwar years big band jazz and swing remained most popular among the upper echelons. At high class clubs and hotels, bands played American jazz standards and adapted pan-Caribbean forms like calypso and merengue, but the more creative players were forming new jazz variations through complex original compositions.

“Big band was also our pop music,” said Winston Blake, operator of Merritone, the longest-running Jamaican sound system. “That was the swing era: Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey, Stan Kenton, Glenn Miller. The formative bands in Jamaica played that music as dance music.”

Chief among the hotel groups were The Arawaks, featuring pianist Luther Williams, and saxophonist Val Bennett’s band. Eric Deans’ Orchestra became the most popular Kingston live act through a long residence at the Bournemouth Club at east Kingston’s Bournemouth Beach; Deans was a multi-instrumentalist whose saxophone skills drew comparison to Glenn Miller. Redver Cook’s band was a favourite of the light-skinned upper class and played regularly at a society spot called the Glass Bucket. John Weston’s 12 piece band, Milton McPherson’s group, The Baba Motta Quartet, Wilton Gaynair Quintet, and Foggy Mullins Trio were among the other popular acts of the period; trumpeter Sonny Bradshaw, who played in several, formed The Sonny Bradshaw Seven in 1950 after organising a landmark jazz concert at Kingston’s Ward Theatre. Down on East Queen Street, where a venue with outdoor gaming tables was designated a ‘Coney Island’ because there was gambling on offer as well as music, a hot house band with a shifting line-up was blowing jazz nearly every night of the week; its members would later emerge as the key set of session players once entrepreneurs began recording local talent.

But working class Jamaicans could not afford the smart venues. Their entertainment was most often provided by the sound system. Inspired by Jamaicans who had visited the USA as casual farm labour and attended dance parties held by Black Americans, restaurant owners and other aspiring businessmen had systems with powerful amplifiers sent down from the States, often with speaker boxes custom built in Jamaica, with which to broadcast the sound. Their sheer power and volume inevitably drew large audiences when booming out at an open air dance, and the advent of the sound system would be a defining element of the island’s homegrown music industry.

Winston Blake’s father, a civil servant, established the Mighty Merritone set in 1950 to earn extra pocket money. Though considerably smaller than the Kingston sound systems, it was the first in St Thomas parish. When Blake Senior died in 1956 aged just 41, Winston and older brother Trevor took over, moving the set to Kingston in 1962, where it would be continually active for decades to come, with younger brothers Tyrone and Monte aiding its expansion. Despite the death of Tyrone in 2012 and Winston in 2016, Merritone continues to thrive under Monte’s direction, more than 70 years after its establishment.

“The situation in Jamaica then was that schoolrooms or church halls was where you had social functions,” said Winston Blake of the early days of Jamaica’s sound system culture, seated beneath a portrait of Fidel Castro in his uptown home. “Then you had the most important part of the Jamaican scenario called lawns, like Jubilee Tile Gardens and Chocomo Lawn, big places that were either concrete slab or wire fence, and you’d have a dance in that area, either at the back of a house or the side of a building – a space where you could put up music. You had control because there was an entrance gate. That’s how the sound system started.”

Low entry prices, the sound systems’ mobility, and the fact that live musicians were not involved meant they could be set up at the most basic country venues. This kind of entertainment was thus accessible to a wide audience who were often barred from the elite live jazz venues.

This is an extract from Solid Foundation: An Oral History Of Reggae by David Katz, published by White Rabbit. Read Steve Barker’s review of Solid Foundation in The Wire 491/492. Wire subscribers can also read the review online via the digital library.

Leave a comment