Read extracts from Hit Girls: Women Of Punk In The USA 1975–83

March 2023

Kate Fagan. Photo by Amy Rothblatt.

Jen B Larson compiles interviews with women who made up local regional US punk scenes over forty years ago. Here Feral House press shares chapters on Chicago acts Kate Fagan and Bitch.

Kate Fagan. Chicago, Illinois. 1980.

After Rupert Murdoch bought New York Magazine and fired 80 staffers in the late 1970s, Kate Fagan was out of a job. “He sat on my desk, and he fired all these people,” she said. But a friend of hers living in Chicago sang the city’s praises. So Kate visited the Windy City, where she picked up shifts as a waitress at the Little Corporal restaurant and stayed to make her mark. She loved Chicago for its creative energy and began bartending at the Jazz Bulls and Kingston Mines, where she saw all the blues greats perform. She also enjoyed folk music and lived with writers and actors, who inspired her. She lived above the liquor store across from the Biograph Theatre and says, “Lincoln Avenue was vibrant!”

Kate had relocated a lot during childhood, moving from the outskirts of DC and going to college in Wisconsin, then lived in London and New York City. She never wanted to fit in, but to find herself. She said, “Moving around so much, you recognised how people created and identified with different kinds of groups. Everyone was searching for who they were and a way to express their feelings.”

After living in London and New York, the art scene in Chicago seemed a little more down-to-earth at first. “In Chicago, there isn’t as much phony-baloney — people are more straightforward." Musically, she said, “Chicago fostered a lot of good punk music because of that. It’s just that the framework isn’t there for people to become nationally and internationally successful. [In Chicago], everyone wasn’t standing around peering at each other from behind their shades,” she says. Then, she started to see a particular type of conformity snake in. She approached BB Spin at LaMere Vipere. She writes, “I took over the lead singing role in BB Spin. The original vocalist was a male, and I sang in the original keys. When we opened for the Ramones, Joey asked our manager, ‘Where’d you find a girl that sings like a guy?’ I took that as encouragement to be a ‘front man,’ like I was successful in a traditional man’s role.”

Then, she picked up a bass and wrote a bouncy five-note riff, adorned with her anti-cool culture critique “I Don’t Wanna Be Too Cool.” She calls out divisive hipster exclusivity in it — the idea of velvet ropes and the “who can get in and who couldn’t get in” atmosphere invading creative spaces. She howls and sings: I won’t wait at Neo / Can’t afford Park West / I don’t really care / I’m just not impressed. I don’t know no rock stars / I don’t snort the good stuff / I don’t really care / I’m just not impressed. In the chorus, she sings: I know your cool is chemical. The local scene loved being chastised. The anti-hipster anthem became a favourite of club DJs, radio stations, and Wax Trax. She had recorded the song at Chicago’s Acme Studios and met the fellow artists with whom she’d formed the Disturbing Records label. This group staged warehouse parties and became a platform for many punk, new wave, and garage bands. Disturbing released the “I Don’t Wanna Be Too Cool” single, as well as early singles by her later, legendary ska band Heavy Manners, for which she is most well-known.

After the original singles sold out in 1980, Kate Fagan did a second run of 1,000 copies out of her own pocket, but the records perished in a house fire where she lost everything she owned. Another song she wrote and recorded, “Waiting For The Crisis,” critiques US international relations and the Reagan-era military-industrial complex. Over its singular plunky, eerie piano note, in the verses she sings: “We sell guns to all our third world friends / We sell guns if they will sell us oil / We’ll sell nukes if you will be our friend. With paranoia-inducing chanting choruses, she sings: Oh oh / We’re waiting for your crisis / We sell hate to offset our deficit” Kate says she found herself writing protest music at a young age. She grew up outside of DC in a highly politicised environment during the Vietnam era when her father was a civil rights lawyer. “I’d run to get the newspaper in the morning to read the editorials on women’s rights, Black power, and the sins of Richard Nixon,” she told Flaunt in 2016. In high school, she wrote for her school paper; later, she earned a journalism degree from Indiana University’s Ernie Pyle School. She states that she“found comrades among the editorial staff.”

In Chicago, she became involved with Rock Against Racism as a political movement and taught art education at Chicago Academy for the Arts. She also fronted the ska band Heavy Manners, who shared bills with the likes of the Ramones, Grace Jones, the Clash, and Black Uhuru.

Kate hasn’t stopped performing, as making music and entertaining is integral to who she is. Describing her experiences performing live, she says, “You’re finding a little burning coal inside you — an essence, you’re finding and expressing it. That’s what punk was. You didn’t just sit in the stands and watch people; you jumped down on the dance floor. That feeling is so contagious and punk really hit it right for a lot of people. They could open themselves up.

● ● ●

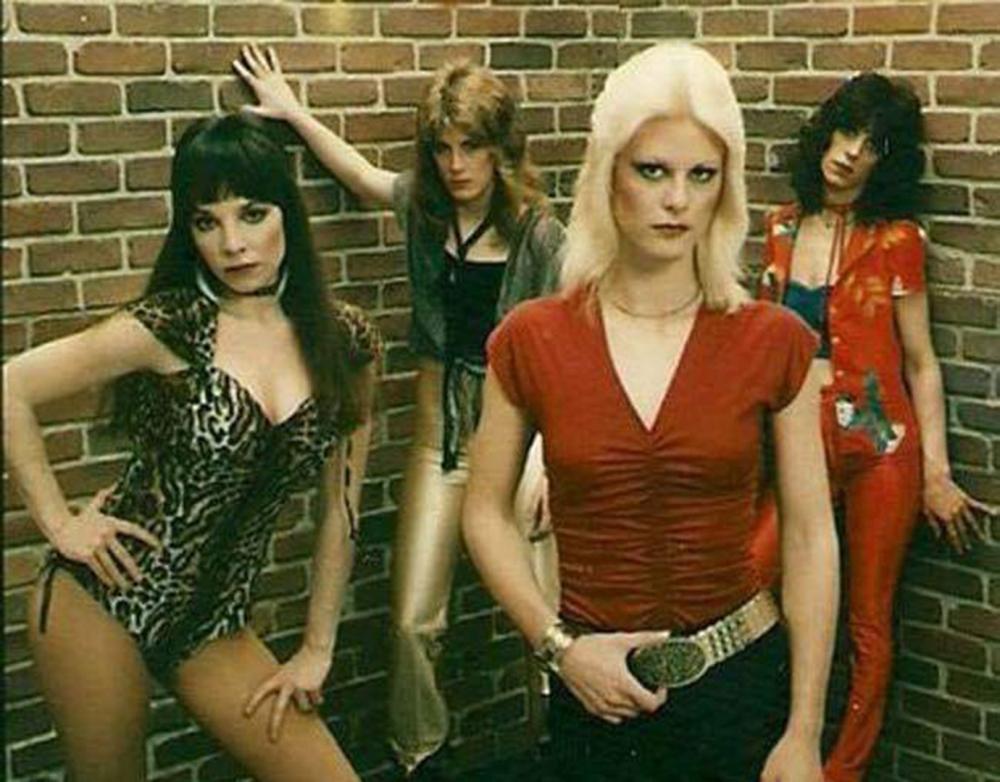

Bitch. Chicago, Illinois. Formed in 1978.

Bitch publicity photo, Chicago, 1979.

During the late 1970s and early 80s, a coven of all girl bands whipped through the Windy City like a pack of wild wraiths. Bitch, Tough Love, The Girls, Surrender Dorothy, Illicit, and Rash, to name a few. The tempest’s catalyst was none other than songwriter and super-shredder guitarist Lorrie Kountz.

Lorrie began playing guitar at eight when her parents, unable to bear the everyday clamour of a yet-to-be-proficient percussionist, returned the drums they originally bought her and replaced them with a guitar and a promise of lessons. Lorrie studied classical guitar for several years, and at 14, began giving lessons. Once she heard Aerosmith and the Runaways, Lorrie abandoned nylon strings for a Strat and Marshall amp.

At 15, she saved up money from teaching guitar and bought a motocross motorcycle. On the bike, she cruised to school and went off-roading with friends. By 17, she traded in the motorcycle for a car to lug gear around for her first band, Bitch. Lorrie passed up a four year college opportunity and put ads in the Illinois Entertainer. Through that and word of mouth, she summoned the first lineup of Bitch. “My parents weren’t pleased,” she said.

She started writing songs and remembers, “It was good emotionally. It was a way to speak. Socially I felt better writing it down, writing music, and getting my point across, whatever my point was at that age. I felt I was better at writing music to describe my feelings.”

Lorrie approached songwriting by beginning with guitar riffs or bass riffs and building from there. Her first songs reflected teen angst. Titles like “Committed,” “Drag Her Under,” “You Come Too Fast,” and “I’m 18” (not the Alice Cooper song!) became Bitch originals. They also threw in covers like “These Boots Were Made for Walking” and “Heartbreaker.”

“I was highly inspired by the Runaways,” Lorrie recounts. The all-girl group put the idea in her head that an all-chick band would be cool.

In their three years together, Bitch underwent a lineup overhaul (adding a lead singer), put out two albums, Love Is Just a Crime (on Orfeón Records) and America’s Sweethearts. Bitch were often listed on marquees or billed in newspapers as “B” or “BIT**” by venues and media outlets; sometimes their entire name was blacked out. Despite this, they packed houses at local venues, performed at city events like Loopfest and Chicagofest, and zealously toured North America. They followed a six-weeks-on, two-weeks-off tour schedule during their prime and made it to 30 states. On tours of the States, they played alongside many legendary acts who were not yet household names.

“We toured with U2, the Cramps, and the Ramones,” Lorrie recalls casually. Bitch opened for U2’s first tour (5,000 seat venues) throughout the Midwest, played with the Cramps in the north (Wisconsin, Michigan, into the Dakotas), and the Ramones on the East Coast (New York City, Massachusetts, and the Carolinas). “That was a hoot, [the Ramones] were so nice.” They also played with Ronnie Spector, the Kinks, and even the Scorpions.

Lorrie recalls touring endlessly, playing regularly in Texas, having a solid fan base in Guam and Mexico (where their label Orfeón was located), and once touring 28 straight days on the way to Los Angeles.

“It was much easier than now. There were actual booking agencies, and you actually made money,” Lorrie says. “You had a lot of support from the crowds, too. The clubs would be packed five or six days a week, no matter who would be playing, so they had their own draw. They were very supportive of the original music back then.”

In the city, women supported one another’s bands fiercely as well. “There was a lot of camaraderie back then. All the females in music were supporting each other. When we were in town and not playing, we would go check out other female musicians and support them!” she says. “There was this band Barbie Army we used to go see.”

“It’s much different than now,” she adds. “It wasn’t competitive back then. When I play with a band now, and there are females in the band, there is not as much camaraderie, not a lot of love going around. Is it generational? I don’t know why it changed,” she says.

Bitch sometimes egged on their male audiences, dedicating songs to “the boys in the room” and naming them “the ones who haven’t become men yet,” before launching into a riff-heavy song like “Come Too Fast.”

The girls didn’t let men push them around, especially the musicians they played with. “I think they were actually a little intimidated by us because we were a little bit edgier. Back then, long hair was in, like big poofy hair was in style, and we wore less makeup than they did. They’d be kind of hogging the mirrors and stuff, putting on their hairspray. So, we would come in there and be like, ‘OK, clear the room’ because it was our turn. They weren’t really used to that. They were used to just kind of hanging out in the dressing room the whole time.”

In 1980, Bitch headlined the Troubadour in West Hollywood to play for potential labels. Kim Fowley happened to be there and approached Bitch founder and lead guitarist Lorrie Kountz, interested in working with her and the band.

“He was a very crude man,” Lorrie says unapologetically. “And I basically said, ‘you know, I don’t think so,’ and he got a big attitude. He would even call me when I was back in Chicago, and finally, I had to tell him to knock it off.”

Even though the Runaways were one of Lorrie’s biggest influences, both on her guitar playing and her vision for Bitch, she didn’t budge. “I just didn’t like him. I didn’t care that he made the Runaways or some of those other bands. It was his attitude that I couldn’ t stand. He was too chauvinistic. We wouldn’t go for that. I didn’t want to go there.”

Lorrie’s patent integrity has always guided her decisions, even when it came to moving on from bands and beginning new ones. In 1981, Bitch changed their name to Tough Love to avoid censorship issues and make it easier to advertise. Tough Love added synths and tried to soften up their sound. With three second-generation Bitch members at the helm, Tough Love put out a few singles and got radio airplay. When Lorrie felt the band wasn’t going in a direction she enjoyed, she left and tried out new outfits. She played in bands The Girls, Surrender Dorothy, Illicit, and Rash before doing solo work and starting her current band Whatismu.

Lorrie says she remembers the time in Bitch fondly. “We had a good time; we were good friends.”

Hit Girls: Women Of Punk In The USA 1975–83 is published by Feral House. Read Dave Mandl's review of the book in The Wire 469. Subscribers can also read the review online via the digital library.

Leave a comment