Greg Tate’s Invisible Jukebox with Alan Licht

December 2021

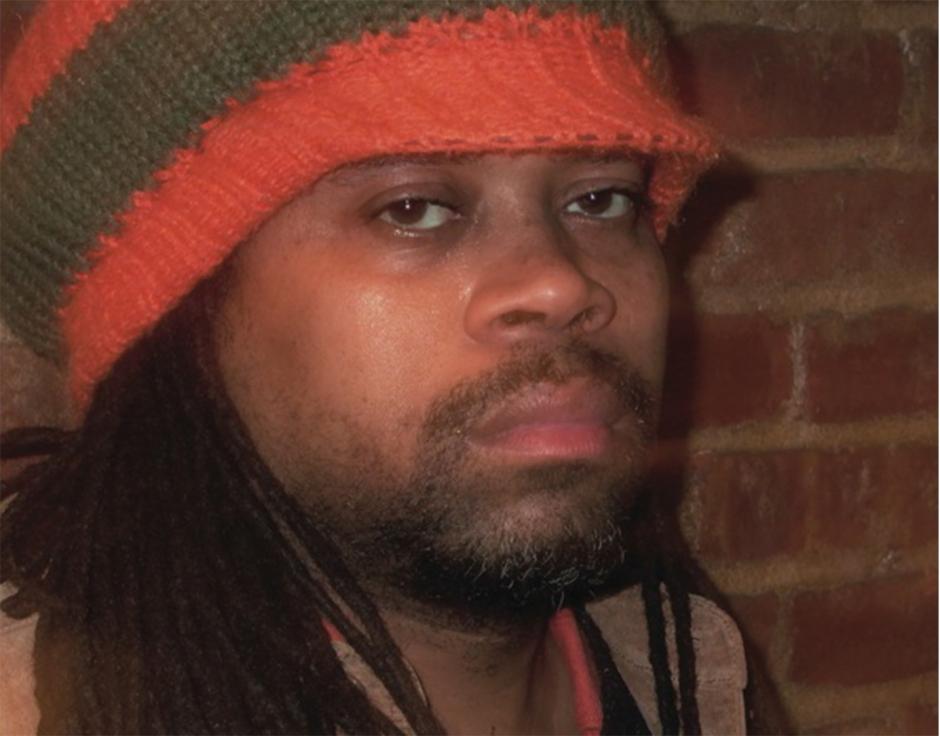

Greg Tate in The Wire 240. Photo: Arthur Jafa

Read Alan Licht’s full transcript of musician, author and critic Greg Tate’s Invisible Jukebox interview from January 2004 for The Wire 240

Original introduction published in The Wire 240: Greg Tate has been involved in the New York music scene, as both a writer and a musician, since the early 1980s. Currently a staff writer at Village Voice, his essays on Black music and culture for that publication and others, including some of the most erudite and insightful writing ever done on Miles Davis, Cecil Taylor, Jean Michel Basquiat, Bad Brains, King Sunny Ade and many others, are collected in Flyboy In The Buttermilk (Prentice Hall, 1992). Tate was a founder of the Black Rock Coalition in the 80s, a local collective from which the group Living Colour, among other things, grew out of. His most recent musical endeavour has also been his most fully realised and successful: Burnt Sugar, with a floating membership of up to 20 players, he founded in 1999 in order to present a melange of jazz, rock, funk, 20th century composition and African music in a post-Miles/Funkadelic/Hendrix/Arkestra improvisational framework. Burnt Sugar also follows the Lawrence ‘Butch’ Morris system of conduction for organising the improvisations, with Tate as the guide. To date they’ve released several CDs for their own TruGROID label, including Blood On The Leaf (2000), That Depends On What You Know (2001) and The Rites: Conductions Inspired By Stravinsky’s Le Sacre Du Printemps with Melvin Gibbs, Butch Morris, and Pete Cosey (2003). Tate also recently edited Everything But The Burden: What White People Are Taking From Black Culture (Harlem Moon) and authored Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix And The Black Experience (Lawrence Hill, both 2003). The Jukebox took place in Tate’s apartment in New York In January 2004.

Cosmic Rays/Sun Ra Arkestra

“Honey”

From Spaceship Lullaby (Atavistic) 2003, rec late 1950s

Greg Tate: Sounds like white label Sun Ra [laughs]. Yeah, I definitely consider myself blessed that I witnessed The Arkestra many, many times in the 70s. There were certain bands that just seemed to be in Washington DC every week. The first place I saw them was kind of like a supper club that mostly did R&B oriented jazz, but they brought Sonny and the crew in for about a week. The one thing I remember about the gig was that at the end of the show the whole band came through the audience and Sun Ra was just saying ‘Give me your death, give me your death’, and he was yoking people around the neck [laughs]. ‘Give me your death, you don’t need it, give me your death!’ And I remember they played this place called All Souls Church, and the church had this amazing organ but they wouldn’t let Sun Ra play it. They ended that show with this chant [sings], “Get that jive, jack, put it in your pocket til I get back/Goin’ out to space just as fast as I can, I ain’t got time to hit your tan”, this real 40s jive talk. Everybody just filed out into the streets, repeatin’ that chant. The thing about that band, particularly when Sun Ra was around, they did a lot of call and response with the audience, even when they were doing the most avant, out kind of stuff.

One of the things you got from this band, and lot of the other bands of that era, was the fear of no music. They cast a wide net and weren’t afraid to reference anything that would allow them to fully express who they were, as musicians, as artists, as African-Americans, as people who had one foot in, one foot out of the whole communal aspect of African-American history. In Frederick Douglass’s first narrative of his life, he talks about being in the woods, this after he taught himself to read, and he’s really talking about Black alienation in a profound way. I think it’s the first time it appears in his literature, the whole notion of the alienated intellectual, and he talks about coming upon a group of other slaves in a circle singing spirituals, and being aware that he was moved and enchanted by what was going on but he was outside of it at the same time. And I think so much of the music that emerged in the 70s, the Sun Ras and the Art Ensembles and Miles’ stuff in his band, P-Funk, tried to both expound on that alienation and at the same time try to shorten the distance between the alienated self and this communal circle.

Alan Licht: I think that’s probably especially true of Ra, since he always played the outsider to the point of claiming to not even being from this planet, but at the same time he was always so fixated on Egypt and African identity through the centuries.

Yeah, and then he also had an Afro-American intellectual’s obsession with discipline. Black people have a certain kind of discipline and respect for people who had created intellectual traditions or artistic traditions, and who represented a certain standard for excellence. There’s always a cultural nationalism behind his stargazing, you know, it’s kind of throbbing underneath the whole thing. And it grows into the whole question of how much his Afro-Astronomics [laughs] was just a performance, a vehicle to speak about more pressing concerns, at an existential level.

George Clinton was doing that too.

Yeah, and to hear Ra tell it, so much of the P-Funk iconography was derived from him. It’s funny, cause you read interviews with Clinton and he says he came fairly late to knowing about Sun Ra, so many guys were telling him, ‘You guys are basically on the same path, the same wavelength’.So he finally checked it out and said, ‘Yeah, that boy’s definitely out to lunch [laughs], the same place I eat at’.

In terms of that whole generation, Coltrane, some of Wayne Shorter’s things, Sputnik was generationally a touchstone for the way they started to think about what jazz had become, or even how jazz was starting to, metaphorically, evolve. That generation saw themselves as afronauts. There’s so much science fiction imagery in the album titles.

I assume you’re not as fierce a taskmaster with Burnt Sugar as Sun Ra was with The Arkestra – you don’t have them living here someplace?

[Laughs] Right. Well, the inspiration for Burnt Sugar came from a couple of places at the same time. I went to visit a black British painter named Frankie Bowling, and he has these massive paintings, I mean 18 by 22 feet, and it made me recall that so many Black abstract painters were devotees of the music of Sun Ra and Coltrane, the cosmological leanings of that, and they were trying to represent that cosmic streak in oils or acrylics. Scale was really important. And I realised the music that inspired that were these 20, 30 minute tracks, that just doesn’t happen anymore in terms of contemporary Black jazz. So I just started thinking about this whole notion of scale in terms of music, having the space to develop things.

And then I remember I was reading Mojo magazine and they have a column where they ask people what’s your favourite record of all time. And I’d never really thought about it, and I just allowed the first thing to kind of swim up and I thought Bitches Brew. That’s interesting because if you asked me what was my favourite Miles record I probably would have said Nefertiti, Dark Magus, In A Silent Way. But I realised that Bitches Brew embodied the spirit of experimentation and had a risk-taking element to it, it was that first voyage for Miles stepping off the jazz stage into something else, something that was crafted as a performance artist, conceptual artist, and the way he used his own mythology, and playing with the laboratory quality of acoustic and electric instruments. Because it has acoustic basses and electric basses, these multiples of instruments, it has this way of being responsive to jazz’s acoustic past and also daring to shed some skin. So I said, hmm, I’d like to pull some cats together, pursue things in a more methodical way than I had before – all the little jam sessions and bands I’d been muckin’ around with since I came to New York all used Agharta as a launching pad.

I’ve been following Butch [Morris] since the first conduction, Current Trends In American Racism, in 85 at the Kitchen, and I just recognised that that whole project is expanding the symbolic territory of jazz, globally, racially, instrumentally. It was and is such a defiance of the ghettoised state that jazz is in now. I think that anybody who wants to have a large band now that wants to deal with electronics, acoustic instruments, and dynamics, there’s going to be some kind of conduction going on [laughs], if you’re not trying to manipulate it all but trying to deal with it in a live presentation – there’s got to be some kind of methodology to spontaneous orchestration. I didn’t want to be perceived as biting off of Butch’s thing, but he’s been very generous, towards me and towards other people. I basically acknowledge that he’s provided a wonderful way for improvisors to move forward en masse. It wasn’t until after we did Rite Of Spring that I really felt comfortable using his system. It’s funny because he told me, ‘You need to get a stick’, a baton, after he saw the band a couple of times, and I was really wary about it. I was really more interested in making records than being a musician or being a conductor.

Because one of the other things that happened around the same time as I had my Mojo epiphany and my Frank Bowling epiphany – ECM had done a book of album cover art, and I looked at that whole catalogue and particularly the early ones, before they settled into the quieter Norwegian sound [laughs], so many great records they did like Mal Waldron, Bennie Maupin, Julian Priester, and I liked the idea that they were trying to find a visual correspondent to the music, and were paying as much attention to graphics and the recording process. My epiphany then was like, Wow, what I really want to do in music is become a Black Manfred Eicher [laughs]. With Burnt Sugar, that was always the intent, this thing was gonna jump off a label. And then the band just kind of took on a life of its own, it found its own way of surviving.

The Mothers Of Invention

“Igor's Boogie”

From We Are The Mothers And This Is What We Sound Like (Bootleg) 1988, rec late 60s

That definitely sounds like an Art Ensemble thing, or the AACM. Sounds very Chicago [laughs]. Even the falsetto sounds like The Dells.

It’s The Mothers Of Invention. It’s called “Igor’s Boogie”, I don’t know if the opening is actually Stravinsky or just inspired by Stravinsky.

GT: Anthony Braxton talked about how important doo-wop was for the AACM in terms of the romance they developed for music as teenagers. And it has all the formal qualities, the upper and lower vocal parts, it’s got this expressive dimension as well. I don’t think anyone has really written about it, but for those guys there’s a particular emotive and formal dimension, cause you think about that music [doo-wop] as being so tightly coiled and performative, but clearly all of these guys that were kind of driven to play out connect with that as a source, that’s almost the three-piece suit that they were trying to break out of. Clinton was talking about how P-Funk tried to be The Temptations, but what would happen was they’d get up there in suits and stuff, going through all the steps, and by the end of the show guys were just climbing out of their suits sweatin’ profusely, he said, ‘We just couldn’t help being funky’ [laughs]. For these guys, being hemmed in like that was really the spark. But I truly believe that R&B, particularly in the 60s and 70s, was the American operatic form. It was so much about these amazing voices, that are so specific to these shores, about these amazing arrangements. When you watch these oldies shows on channel 13, which really make you feel old because the music that is considered oldies now was Top 20 when I was a teenager, but it’s so classical in terms of the form, you want to hear everything in the same place it was on the 45. The level of orchestration and arrangement, as well as the magic of the voices, is so specific to American music and to an American interpretation of European classical composition. It really starts in doo-wop and becomes more instrumentally pronounced by the time you get to Motown, and by the time you get to Thom Bell and the Gamble and Huff guys it literally becomes symphonised, the Philly International band as well. The fact that they’re creating this symphonic form, partly through orchestration, notation and partly through improvisation, with 25 of these guys, string players and horn players, jamming to create these tracks for the O’Jays or whoever.

Zappa is one of the better known people of the 60s who started tracing these leftfield connections between different kinds of music, between doo-wop and Stravinsky and free jazz, how much of that have you consciously put into your writing or with Burnt Sugar?

One of the things that’s interesting about The Rite Of Spring in particular, it seems to be the most treasured piece of the European canon by jazz musicians, it seems to have always been that way since Ellington. It has basslines, it has this staggering percussion going on. But later on when you start to hear the AACM cats starting to do music for saxophone quartets, in terms of their own improvisational interplay the inspiration is The Rite.

How did you decide to record it with Burnt Sugar?

Vernon Reid’s wife [choreographer] Gabri Christa had approached me about doing a collaboration with her at Summerstage in Central Park. It was one of those three in the morning inspirations, I knew there were a number of amazing versions of The Rite in the dance canon already: Balachine’s, of course. I told Gabri that we really need to bring Butch in, because he’s got a lot more chops as a conductor, but also as someone who’s actually collaborated with dancers, and she was open to that. In rehearsals she adapted a lot of Butch’s cues to choreography and used those at the performance. I went through the piece and pulled out three sections that I thought we could really play around with, then he listened to it and he brought in three other motifs. And then Vijay Iyer actually brought the score in, and used a couple of sections from the score to develop, there’s certain sections of contrast, staccato percussive kind of playing.

I thought some of the things that developed in the rehearsals and the performance were staggering. Jared [Nickerson, Burnt Sugar bassist] happened to be out of town so I called Melvin Gibbs, and then Pete [Cosey] happened to be in town, so I asked him to come down and work with us on this thing. He came down spent the day, and the rest is mystery [laughs].

Funkadelic

“All Your Goodies Are Gone (The Loser's Seat)”

From Funkadelic Live At The Meadowbrook, Rochester, Michigan 12 September 1971 (Westbound) 1996

Definitely sounds like early Parliament, like the Parliament singles.

Yeah, it’s Funkadelic live, the song was an early single, but after three minutes this is already longer than the original, [GT laughs] and it goes on for 15 minutes.

George Clinton and Parliament is so much about the reinsertion of the spookiness, the ghostliness of the Pentecostal church into this smoothed out R&B frame. If you just heard the singing you’d just think this was some Alan Lomax recording from the 40s or the 30s (laughs), it’s just real backwoods in terms of what they do with the doo-wop thing. There’s so many churches, in Black America, each one has made its own peace with how closely aligned it is with the Euro-American mother church, and that includes the musical, expressive side. The people who come out of that Pentecostal background just go out for the screaming – Little Richard, James Brown – but what’s really interesting about this is that it’s got the scream but then it’s at a whisper too. Maybe it’s also a Catholic influence, combined in the course of the personnel coming together who may have had those two influences. Clinton said that melody for “Flash Light” was a bar mitzvah melody he heard as a child, so I guess you have to be cautious of trying to attribute influences to any one source, especially with P-Funk. But it’s part of the anthropology of Black music, in the same community or the same household, sometimes, you can have all these different strands, what church people belong to, what their connection is to the street, or what their connection is to higher education. You can’t ever really easily suss it all out.

This is coming out of the same time period that Quicksilver Messenger Service is taking a Bo Diddley tune and stretching it into 20 minutes, and one source of all of this could be what Coltrane did with extending “My Favorite Things”.

It also unfolds like a church ritual, some of those services would start at nine in the morning and go on till nine at night, their cultural experience encompassed this kind of longform expression too.

There’s a whole tradition of devotional music being longform. People are used to hearing an Indian raga on an album side for 20 minutes but in fact they can last an hour and a half or two hours.

I was talking to King Sunny Adé and he was saying the sets that we [Americans] saw were so truncated by comparison to what they were doing in Nigeria. Some of these concerts would literally go on for days, Fela was the same thing. Part of the aspiration of so much of the music in the 60s was trying to figure out how do you actually reduce this ritual extravaganza to an efficient pop form. P-Funk was marvellously adept at doing that, over the course of their career they kept going back and forth between things that could literally be stretched out 20 minutes in a concert and would completely work in a three minute pop frame without losing any of the ability to engage an audience on a dancefloor or in an auditorium.

Rock Workshop

“You To Lose”

From Rock Workshop (CBS) 1970

Sounds very San Francisco 1968 to me, I’m thinking like Jefferson Airplane, Mother Earth, something like that.

It’s Ray Russell, a British jazz guitarist, a studio guy who became a free jazz guitarist. He has a couple of records that are more like the crazy stuff he was doing a minute ago.

Yeah, the guitar sounds definitely reminded me of [Jefferson Airplane’s Jorma] Kaukonen, [Quicksilver Messenger Service’s John] Cipollina, [Chicago’s] Terry Kath too, it sounds like a lot of that early Chicago, almost college big band jazz [laughs] with San Francisco rock.

Ray Russell is an example of a jazz guitarist who heard Hendrix and then…

GT: [Laughs]… said, ‘I want to go over the hill too’. Yeah, when I hear that stabbing heavy vibrato sound, you’ve just reminded me how much that was a part of the surf music sound that he killed [laughs]. Nobody knew what to do with the tremolo bar until he came along. And just sonically how he brought this horn legato into the thing, and distortion, everybody recognised the power in volume and distortion, but he brought finesse into it. There’s something comical, almost hysterical about that approach to playing.

In a way he redefined the guitar as an electroacoustic instrument – Pete Townshend and Jeff Beck were using distortion and feedback, but Hendrix was the first to use effects the way Stockhausen et al were using them in a studio.

Yeah, but there’s a great quote from Michael Bloomfield, where he says he never heard Hendrix do anything on record that he didn’t see him do live at the Café Wha with a distortion pedal and extreme volume, and his hands, more than anything. When you watch films of him, it’s uncanny how his body seems to anticipate what the next note is going to be, even if the next note is feedback. He’s harmonising the feedback, he’s playing melodies with the feedback, the control is just sick.

I was talking to Melvin Gibbs once about the turning to the amp kind of feedback, which a lot of people still do. I said, The thing with Hendrix is you realise he’s 20 feet away from the amp and doing the same things as the rest of us run up to the amp to do. I can’t think of anybody who is in that control of the chaos, in the moment, and then finds such orchestral uses for it.

It’s like a one-man conduction.

[Laughs] It’s kind of crazy. His neurological command of the instrument remains unparalleled.

Jazz Composer's Orchestra

“Communications 9”

From Jazz Composer's Orchestra (JCOA) 1969

Is this Cecil [Taylor]? Into The Hot?

It is Cecil, but not that record.

Or maybe The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra?

Yes, the organisation set up for musicians to get together and play each other’s pieces. Can you relate that to the Black Rock Coalition?

Oh, it’s funny you say that, because one of my biggest issues with the Coalition when I was in it was around this whole question of rival models, and one of the things I knew about the AACM was that they really insisted that people develop new compositions, that was an artistic imperative. I really feel like the Coalition stagnated in the 80s, because the pursuit was trying to function within the American corporate rock ’n’ roll context, so the ambition became to get a record deal, which brought about my other pet peeve, which was that people didn’t release their own music. And it only became exacerbated when Living Color got a deal. One thing about the Coalition that not too many people know is that when we first started, there were very few musicians who were associated with us, because they were afraid of being blackballed or blacklisted. Most of the people who came in were from all walks of life, we had guys who worked on Wall Street, school teachers, concert producers, but they were kind of 60s/70s holdovers in terms of a belief in radical collectives, radical communities. And then that flipped, once Living Color blew up. In some ways that was the beginning of the end for it as an artists’ collective.

When The Black Rock Orchestra came together, it was at varying times like an attempt to replicate The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra or AACM, but it was really about challenging musicians to do things that took them out of their comfort zone. Like, what does a post-bop player do with a Robert Johnson song? In some ways Burnt Sugar is kind of a way for me to pick up on some of these paths and not to do it inside of a contested, kind of bureaucratised notion of a Black Rock Orchestra.

You hear so many different kinds of music in Cecil Taylor’s playing, especially his solo work – is that an influence on Burnt Sugar too?

GT: It’s really a group of New York musicians, which, for me, means people who have pretty much designed themselves to be able to play anything depending on where the call comes from. Cecil is such an ingrained, pivotal figure in terms of how I think about how you function in the modern world as a creative person. What kind of sacrifices, what kind of choices you make, what you decide not to do after a certain point. When I first mentioned the Into The Hot thing, what’s interesting is that Cecil wrote orchestrations which are very similar to this, but then Henry Grimes and Sunny Murray are playing more swing-oriented music than they ever played again throughout the rest of the 60s. It was this turning point for Cecil where he was still engaged with this finger-poppin’, head-boppin’ kind of swing and you hear that in Looking Ahead, that’s the last time you’re gonna hear Cecil engage with the whole notion of swingin’ bass, swingin’ time on the ride, and the whole thing. There’s a really extreme subtraction in terms of his aesthetic across time.

There’s that insane collision between him and Mary Lou Williams [Embraced, 1977], a duet where it just becomes clear that Cecil is not compromising with anybody just to get along, or just to prove his legitimacy to the rest of the jazz world. ‘This is who I am, this is what I do, take it or leave it.’ And you think that that’s some iron-fast stance, and then you hear him in the band he has with Thurman Barker playing marimba and vibraphone and it becomes more subdued, the swing elements begin to percolate. And in his collaboration with The Art Ensemble, the duets with Max Roach, the duets with Elvin, he feels like his contribution is unquestionable, he’s written his chapter in the book of what jazz has become, and he fortifies anybody who is trying to not just go against the grain but split the board in two [laughs] in the process.

I’ve heard him talk about the way he sees what he does on the piano is really trying to emulate forces of nature, whether it’s waterfalls or forests or mountain ranges, and I read an interview with him recently too where he talks about doing a residency in Banff, and going out one day in the snow and seeing a deer. That encounter really shook him in a way, because there some kind of eye to eye contact between him and the deer, and he felt like he didn’t know how to respond to the way that deer was at home in nature. And he said, ‘The next time I come back I want to have something to say [laughs] to that deer.’ This encounter with the deer made him think about being able to actually transcend the piano, made him think about who he was as an artist in a way that wasn’t reliant on the tools. It was thinking about himself as a work in process. It’s just noble.

Howlin’ Wolf

“Spoonful”

From This Is Howlin’ Wolf’s New Album (Cadet) 1969

[Laughs] I knew Pete [Cosey] was gonna show up in here somewhere: [Muddy Waters’] Electric Mud, Rotary Connection, or Phil Cohran, and it’s the Wolf record. Yeah, I remember listening to these records before Pete went with Miles [in 1974–75]. This is a record I found around the house, my parents had a Chess greatest hits thing lying around the house, Chuck Berry was on there, Muddy Waters was on there, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy.

Did you realise it was the same guy who played on this record when you first heard the Miles stuff?

Oh, not at all. Pete was in Miles’s band for about a year before I actually heard him, friends of mine who saw him said there was this incredible guitar player with a huge afro, got a bunch of percussion instruments, crazy pedals and the whole thing. What’s interesting about Pete’s tenure with Miles is the way his sound changed in the course of playing with that band, because when he came in, he was kind of like a stabbing vibrato kind of guy. I saw the band in late 73, early 74, and by that time he had really developed that whole swallowed note, weird volume pedal fuzz subterranean scalar thing, some weird Cheshire cat guitar, man. He was tunnelling through something and then it would just suddenly pop out again and scream and then disappear – the dynamics were crazy. That band too… Miles made it scary, because those guys kind of made it familiar and strange at the same time, ’cause they looked like friends of mine [laughs], like guys playing in R&B bands, they’re using a lot of that vernacular, but to various devious ends. When I went back and listened to Pete on some of the Rotary Connection stuff and Electric Mud, he must have been experimenting with all this stuff at home, it wasn’t until he realised he wasn’t gonna get fired from Miles’s band [laughs] that I guess he really started pulling out all the stops. I’ve never asked whether it was a conversation [with Miles]. The funny thing is you hear a lot of bootlegs of the band, it’s going back and forth, sometimes he’s still playing in the trebly, kind of chromatic…

Right, in 73 he’s not using that much distortion.

Yeah. But then Get Up With It was recorded in 73 so he’s doing other things that are interesting like the kinda phased sound on “Calypso Frelimo” or the sitar-ish kind of sound on “He Love Him Madly”, and then on “Mayisha” he takes a kind of fuzzy solo there. But you hear Agharta, and not even seeing the band prepares you for it, that first solo… In some ways it’s the first time you’ve heard somebody take the whole free jazz guitar thing beyond Jimi Hendrix. But in some ways that Chicago blues thing was more pronounced in Pete than in Hendrix, the attack is just gutsier; those guys were like, ‘If I don’t play this note right now I’m gonna kill somebody’ [laughs], and Pete, from being in that environment, just has that urgency.

One of the things I was always conscious of, as somebody who played guitar, was there really was no space in horn based music, even in the avant garde, for loud-ass guitar players [laughs]. Even Sun Ra: there was another Chicago guy, who was actually one of Pete’s students, named Dale Williams, when he played with Ra, it was still kind of toned down. Miles was the first environment I can think of where a guitar player got to be that noisy, that discordant, that greedy [laughs] with the space, and not get run off stage. Even in Burnt Sugar that contest still goes on – horn players cannot stand being in front of a loud amp, for the most part.

This Howlin’ Wolf record and some of the Miles records in the 70s were not terribly well-received at the time [laughter], but now are more appreciated.

Yeah, I guess I was like a Chess traditionalist, I’m still not a convert. Those original Chess recordings, man, they still sound more psychedelic than anything that’s kind of psychedelic by design. The older Muddy and Howlin’ Wolf stuff to me still sounds more avant garde, and some of it is because they’re not built on straight beats or 12-bar chord progressions, it’s so personal to those guys and their relationship to their bands, and those bands knowing how to accent and bring certain nuances to it. And that music is designed to follow vocals, they have their own system of conduction in the vocal sound. Wolf said he had three guitar players because he loved the friction of them trying to figure out how to work inside of a particular groove or a particular riff, the way those drummers kind of stagger beats or drop beats, leaves tremendous holes there… There’s a part of it that seemed like a certain kind of pandering, not even to a hippie audience so much but the Chess family’s crass idea... [laughs]

of the marketplace...

... of the youth market, you know what I mean. I just wish there was more Pete post-Miles, because he has so many tremendous ideas – when you talk to him, compositionally, his ideas are as out as anything you’ve heard Braxton talk about. There’s a lot of realised Braxton, I wish there was more realised Cosey. It’s kind of scary when you think about his age, the fact that somebody with that much knowledge about the instrument and who’s also developed so many tunings and approaches to the instrument, to leave without passing it down, at some point, even if it’s just being documented. He came into the [Burnt Sugar Rites] session with a Line 6 [loop pedal], he was still on top of the gear. He’s somebody who’s the sum of such an incredible body of experience, from his family and their connection to the swing era all the way to his work with Pharoah, Phil Cohran, AACM, he is really the guitar cat in the middle of all of that, somebody who was a mentor to Chaka Khan, and then his experiences with Chicago blues and with Miles.

Henry Kaiser & Wadada Leo Smith

“Big Fun/Hollywuud”

From Yo Miles (Shanachie) 1998

It’s funny because I really can’t place the trumpet player, but it reminds me that Miles and Lester [Bowie] are the only trumpet players I really want to hear playing over a funk beat [laughs], and this reminds me of both of them in different ways.

It’s Wadada Leo Smith.

Oh, is this the record with Henry Kaiser? Yeah, I was thinkin’ that. He’s really got that rhythmic thing that Miles had down so well. This also makes you think about how much Miles loved Sly Stone. Not just in terms of the groove things, but Sly’s vocalising reminds you so much of the way Miles used the wah-wah too. It’s really fascinating when you listen to the electric records how Miles is just continually subtracting things from his sound to really make it work in the context of polyrhythmic funk, recognising how little space there is for brass. By the time you get to Agharta, there’s speculation about whether he was dealing with illness, or whether he lost his chops, but conceptually, it just seems like those two or three notes he’s playing, the kind of split, bent quality to it… it reminds me more than anything of Billie Holiday’s “Lady In Satin”, where the voice is gone but then the shell of the voice is all this incredible, deeper, wretched emotion.

Wadada also uses space extensively in his playing. When I’ve seen him play in the last couple of years, it’s so sparse.

Yeah, the funk groove is so thick you really can play just one note and whatever’s going on in the rhythm will just complete the thought. Funk is so much about the space between the notes, the syncopation, what’s stressed and what’s weak, the interaction between a particular bass player and drummer. The same thing with the Afro-Cuban stuff, it’s a telepathy between these rhythm players, kind of the agreement they have about what a groove is. Kind Of Blue is where Miles really represents how his generation felt time and space. And after that he had to adapt to how successive generations felt about it, and knew that, if I wanna get to that thing that I like about the way Hendrix and Sly experienced time then I gotta get some guys who generationally are also feeling that, and I’m gonna find my way inside of that thing.

One thing I was thinking about, in reference to this conversation, is about race and music and how we still haven’t gotten to a point yet where you could really talk about all these things being 20th century creative enterprises, even in terms of the critical conversation about it. How race just kind of creeps up, in terms of the divisions that exist between European avant garde, American avant garde, the jazz avant garde, the Black Mountain side of things. They’re not only going on simultaneously, they’re also drawing an enormous amount of inspiration from each other, or even inspiration in terms of defining themselves against each other. Cage talks about hating improvisation, but then his work is so much about another kind of improvisation [laughs], just operating in another space. And then you’ve got the fact that so much of the inspiration for all of these things was African or Asian music as well, but I think we’re still at a loss for talking about different kinds of cognition in music.

OK, hold that thought [laughter].

John Zorn

“Milano Odea”

From The Big Gundown (Icon/Nonesuch) 1986

It’s wild, it makes you think of B-52’s, Fred Frith and King Crimson, all in the same piece [laughs].

Fred Frith is on this.

Definitely sounds like it. Sounds like a Laswell thing, but it also reminds me of the No New York period stuff. [Looks at album sleeve] Oh! I actually have this.

So it’s Fred, and Jody Harris, and Arto Lindsay, and Melvin Gibbs, Anton Fier and Zorn on this track. This album is to some extent a product of New Music Distribution Service.

Yeah, yeah.

Yale Evelev, the producer, ran NMDS and then he moved over to Nonesuch and got this project on there. Anton worked there, and you did the introductory essay for one of the NMDS catalogues. All these players were involved in very cosmopolitan avant garde projects. I wonder if you see New York as a place where the boundaries between the different avant gardes start to disappear?

Well, that’s what so interesting about that particular period. I first started coming up to New York from DC at the tail end of the loft era, and that period was so much about the consolidation and conglomeration of all these regional avant gardes, the New England guys were here, the Chicago guys were here, the California guys were here and they were all playing together nightly, and I feel like that was the last time jazz had a street life in New York. You could start at nine in the evening and bounce from Great Guildersleeves, the Downtown Ocean Club, the Public Theatre… Anthony Davis would play with Frank Lowe and Rashied Ali one night, and Anthony leading his own group the next night, and Arthur Blythe, and Sam Rivers’s big band: in terms of playing with their peers with nightly changes of combinations it was so vital. But by the time I got up here around 82, that’s when the whole No New York, punk jazz, James White And The Blacks, becomes Defunkt, Laswell and Zorn kind of get mixed in, it was this moment where the segregation between black and white avant gardes momentarily dissolved and then reformed again. And then on top of that, the critical support, of all that stuff had been going on in the 70s, which really was Stanley Crouch [laughs], kind of dropped out and shifted to Wynton [Marsalis], and that whole kind of achievement.

The thing about Zorn which I have always admired is his comfort with guitars and guitar players. In a lot of ways he’s an extension of AACM thinking into New York, into the 80s, mixing up genres and feeling completely comfortable working with the European improvising vocabulary and pop elements. They had a precedent in Art Ensemble, in Frank Zappa, in Braxton; by the time you get to the 80s he’s the only guy on the ground in New York trying to have a go at making a language out of all these possibilities.

This record is about Zorn’s record collection as much as anything else.

GT: Oh man, yeah, I was gonna say – I had these two revelatory moments, walking into Phil Glass’s house one day, and Zorn’s, and getting a look at their record collections. Zorn’s of course is staggering; if you’re a record fiend, you just look at the African section with the same awe as you might look at a Monet at the Modern [laughs]. And then with Glass, I remember seeing a BT Express record. It’s like, OK [laughs], I guess I can see a connection.

There was also Kip Hanrahan, who was doing these recording projects using Arto Lindsay and Anton Fier but also all these Haitian musicians, a real cross-cultural combination, probably even more so than John Zorn.

GT: Kip is interesting too, for me, in terms of people who just think about production in a real objective and conceptual way too. He’s thinking about albums from beginning to end. Quincy Jones is really important to thinking about that, Steely Dan is really important to that, certainly The Beatles and Hendrix too, but because of the other things they’re remembered for, you just forget about how massive they were in putting together a body of albums.

DJ Olive

“Funky Cortado”

From Bodega (The Agriculture) 2003

I don’t even know who this is, but yeah, this is the disembodiment of soul. There’s something about the implication of drum ’n’ bass here. Drum ’n’ bass was really on its way, before it became so…mannered, to suggesting some of the spookiness we were talking about in the dub things, Chess things, the Miles and electronic things as well. This is also a recognition of the deathlessness of doo-wop too, and the way that the voice always creates a space for itself inside of whatever kind of music. Music like this is so much about presence and absence too. I like this a lot.

This is DJ Olive. How much association did you have with the whole illbient scene?

GT: Oh, a lot. [Soundlab’s] Beth Coleman and Howard Goldkrand I knew before the illbient thing. And Paul [Miller] worked at The Village Voice as an intern while he was still in school just as he was starting to formulate the whole DJ Spooky persona. They were really on it in terms of understanding the connection between the AACM desire to dissolve all Black musics into their own alphabet soup. One of the problems was it was much more difficult to create a body of recorded music around it, because so much of the way that they worked was so much about acknowledging the sound sources like hiphop did, but by the time illbient emerges, the copyright laws are so prohibitive [laughs]. Some of the best things they did, and in some ways I think this is analogous to the Black Rock Coalition, were never documented, you literally had to be in the space, at the time, to really get it. I think the drum ’n’ bass, illbient moment is something that people are gonna return to, later on, particularly because it’s so evolved in terms of a sensual atmosphere, which is something that’s just been lost in jazz, starting to be lost in hiphop, still kind of there in Detroit techno.

When I hear something like this Olive piece, it has this breath and this openness, you could move a Braxton symphony [laughs] through there, and it can just pass in and out. It’s ghost town music, in a way, so you can just run any kind of ghost through there and keep mushrooming out, without having to be burdened. There’s something about this form that really allows an engagement of history but without the burden of history. The complement to that is Timbaland and Missy’s work, and RZA’s stuff as well, because they’re all about really creating atmospheres, within a dance-oriented context, at least Timbaland. With Wu-Tang, I think what was really interesting about that moment was that RZA really solidified hiphop as a new kind of psychedelia, it was such head music. When you hear it in a club, it’s not as potent, because it’s about being restrained and pulled back, and so literate at the same time. It’s headphone music in a lot of ways. What’s powerful about Missy and Timbaland was they really found a way to put all these avant garde ideas – Cage, Stockhausen, it’s all fuckin’ right there but it’s happening in this pop framework and people don’t even have to recognise it as such, it’s so effective at employing all of those things. I did an interview with Missy where she was saying that the thing about working with Timbaland is that he collects music from all over the world. When they go into the studio, that stuff is playing all the time, it almost makes her scared to go in the room, because he’s playing all this ritual music, but his genius is his ability to summarise that.

Butch was interested in working internationally, forcing, in a very light-handed kind of way, a conversation, not just between different styles but between whole cultures and traditions too. Which is something that Miles did very effectively with OnThe Corner. The thing about On The Corner and some of the stuff on Big Fun, is yeah, he’s got a tabla player, a sitar player, Brazilian percussionists, but they never sound like flavour of the month, he makes them work to figure out how they’re going to adapt to this form, it’s not like they’re the exotic icing on the cake. I think the Illbient project, Butch’s project with conduction, and the Miles stuff, there’s a continuity there in trying to instigate a dialogue within the form itself.

Olive also comes out of what Christian Marclay was doing, and Christian was using turntables at the same time that hiphop was starting to use them. I remember him telling me he tried doing some kind of show with hiphop DJs and it didn’t work at all.

In hiphop, turntablism inspired what everyone was doing with samples, it was before the notion that the purpose of turntables is to scratch, before that you got “Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel”, which really is about storytelling, and I remember seeing sets by Afrika Bambaataa where it was really about creating these paragraphs and sentences from 20 different records in a short amount of space, and Jeff Mills, and amazing house and techno DJs who are just using fractions of seconds, creating this heightened sense of drama and suspense. But it’s really more alive with someone like Christian, because it is performative but I think the whole turntable contest thing has really reduced turntablism to the new guitar gladiator contest [laughs].

Jimi Hendrix

“Young/Hendrix”

From Nine To The Universe (Reprise) 1980, rec 1969

Is this the one with [John] McLaughlin playing, that bootleg? I know it’s Larry Young and Jimi…

It’s Nine To The Universe.

Oh, OK. There’s one tape where McLaughlin’s playing acoustic guitar, and maybe Dave Holland is the bass player, I think I heard it once. Yeah, the great what if? [Laughter] What if Miles hadn’t asked for $75,000 the weekend before that session he was supposed to do with Jimi and Tony Williams? That’s one of those things where it’s just like… I’d settle for a minute [laughs], just to hear the possibility of it. The thing with Hendrix is you realise how much music changed the year after he died. He was kind of searching for his community, his home, and it emerged the year after he died, that’s when fusion happened, it’s the year before Bob Marley And The Wailers come out, before Stevie Wonder starts using Electric Ladyland, all these people who had been inspired by him, they figured out their own music, and they kind of defined what music was going to be for the next ten years. You just feel like, man, if this guy had lived another year… he could have jammed with everybody from Joni Mitchell to Kiss to Bowie [laughs], to Mandrill, to Miles, and God only knows what he would have come up with. Larry Graham said that Jimi wanted to put a trio together with himself and Greg Errico, which would have been just amazing.

I think it would have been impossible for Hendrix to find the R&B audience he wanted without another singer, because the standard for singing in that Al Green/Teddy Pendergrass era [laughs] was so high, there had to be someone else on the vocals, and I think Hendrix was cool with that too. People recount conversations with Robert Johnson where he wanted to have a Basie-like big band and Hendrix was thinking the same way, wanting a band with horns. And I always wonder too if he would have been able to accomplish what The Isley Brothers did, in terms of having a song on the R&B charts with full-blown guitar solos. I guess I’m obsessed with how he was going to resolve his sense of alienation from the larger Black community and Black popular music at that time even though his contribution was definitely felt by the musicians, it shows up in all this R&B, particularly between 1970 and 75.

How did your Hendrix book come about?

I had done an introduction to a book of [Amiri] Baraka’s fiction, and the publisher asked me if I wanted to do a music book. I said I’d like to do something on Hendrix, because actually I’d never written about him. It was kind of bizarre, once I thought about it, but there was just never an occasion where I got to go long on Hendrix the way I had with Miles or Cecil. I decided to get really narrow: I was interested in how Hendrix conceived of himself racially. The way the book is structured, I wanted it to really be a conversation among Black people about Jimi Hendrix, which is something I never really read other than maybe the times when people interviewed Buddy Miles or Billy Cox. I thought it was an opportunity to bring new voices into the mix, and then go farther afield from that. I was interested in talking to people who themselves had an engagement with Hendrix in a Black communal kind of thing, how they read him and how he read his own alienation.

Xenobia Bailey, who knew Hendrix when they were children in Seattle had a lot to say about that community, which was really fascinating. She talks about how the improvised music people played in that community really didn’t observe the boundaries between genres: you heard spirituals, you heard blues, you heard jazz all at the same time. It was longform, people played well into the night, it was inter-generational, it had a spiritual quality she thought was really specific to that community, where she thought music was more important than the church, it was in every home. And then she talked about how Hendrix, to her mind, was not the best guitar player in that group of guys he hung out with, seven guys that all got together in the house and played loud all night long. She talked about the finesse and the control these guys had over volume. This is a cat who really took a tribal sound, a Black American Seattle sound, and brought it to the world.

I had a friend do Hendrix’s astrological chart. It was funny too, ’cause my editor thought of astrology as this white hippie thing and I was like, man, it’s such a Black thing [laughs], in terms of the dialogue people have about the signs and charts. I didn’t even know white people believed in astrology till I came to New York [laughs]… so he left me alone after that.

Greg Tate's Invisible Jukebox was published in The Wire 240. Subscribers can read the issue online via the digital archive. A selection of articles written by Greg Tate for The Wire are available to read for free via our website for one month.

Leave a comment