Crossing the border: an interview with Savage Republic’s Bruce Licher

January 2021

Tony Rettman talks to the Savage Republic, Scenic and Independent Project Records founder about 40 years of California underground music, monotonal guitars and his Grammy nominated letterpress printed artwork

| Project 197 “Nine” | 0:02:00 |

| Savage Republic “Flesh That Walks” | 0:03:19 |

| Kommunity FK “Anti-Pop” | 0:02:50 |

| For Against “Shine” | 0:04:06 |

| Scenic “Carrying On To Cadiz” | 0:06:01 |

| Woo “Water Drum” | 0:02:26 |

| Savage Republic “Kill The Fascists!” | 0:02:23 |

| Shiva Burlesque “Who Is The Mona Lisa” | 0:03:44 |

| Half String “Shell Life” | 0:06:41 |

| Jeffrey Clark “Exploded View” | 0:04:14 |

| Bruce Licher “Owens Valley Driving Music, Part 4: Lower Rock Creek Road” | 0:09:56 |

As an early convert to the punk scene building up around him in Los Angeles, Bruce Licher sought to create something that did not adhere to the quickly forming stereotypes of the genre. Established in 1980, his Independent Project Records label managed to squeak out a spot of autonomy within the scene with its silkscreened, letterpress printed and hand-assembled packaging and penchant for releasing adventurous units such as Kommunity FK, Camper Van Beethoven, Human Hands and Licher’s own band Savage Republic. He’s a two time Grammy nominee who has designed and printed artwork for an array of artists as diverse as REM, John Lee Hooker, Polvo and the recently departed Harold Budd. P22 Type Foundry recently published a book of his artwork entitled Savage Impressions: An Aesthetic Expedition Through The Archives Of Independent Project Records & Press. Right now he is gearing up for an extensive reissue campaign of the label in 2021.

Tony Rettman: The way I usually like to start off interviews such as this one, is to ask where your interests were prior to the discovery of punk rock in the late 1970s.

Bruce Licher: The first music I ever paid attention to is when I discovered my father’s Spike Jones 78s. He ended up buying me some from an estate sale as a kid. So, that was the first music I ended up collecting. When I was 12, I started listening to AM pop radio. I had missed the 1960s completely. So for a couple of years, I was into Top 40 music. The first record I ever bought with my own money was a Bobby Sherman single. I had an older brother who was into Neil Young and prog rock and he ended up discovering things like Hawkwind and Amon Düül II. When he went off to college, he left his records and that started broadening my interests. Then, when I went into college, I got into jazz for a little bit because there was a bus I took to get across campus and the driver listened to a jazz station. I started getting into heavy metal, but punk came around and just washed all that stuff away!

What drew you to punk?

It’s interesting because up until that point, I saw Blue Öyster Cult, and Pink Floyd on their Animals tour. I had shoulder-length hair. My older brother started hearing about punk before I did. He was asking me if I was paying attention to it. Not because he liked it, but he thought I would like it. I was in college in a photography class in the art department of UCLA and some friends of mine from the class had started going to see bands at the Whisky A Go-Go and I thought I’d go photograph. So, I took my camera and started photographing the bands. I was taking pictures of some punk band at the Whisky A Go-Go in my shoulder-length hair and Pink Floyd shirt. I don’t know why I did that!

Halfway through the set, some little punk girl came up to me with a Marks-A-Lot marker and began X-ing out my Pink Floyd shirt. I tried to stop her and she wouldn’t stop and the guy that was with her was like, ‘Oh c’mon! Let her do it!’ It was then I thought, she already wrecked it, so why not? After she was done ruining my shirt, she grabbed my hair and shook it and danced off. After that, I began to think, yeah, I should probably get a haircut!

After discovering punk, when do you get the idea to make records and make them be more than just a record?

The record that convinced me to buy a guitar was the No New York compilation Brian Eno produced of the no wave bands from New York. By then, I had been going to punk shows for a year and thought it’d be fun to up there playing but I couldn’t imagine it. As simple as punk rock was, it was still beyond what I thought I could do. But when I heard Mars and DNA on that album, they broke it down into such interesting and unusual sounds that it just clicked in my head that I could do this. DNA in particular was inspiring with the simple repetitive thing they did.

So after that, I went out and bought a cheap guitar. I didn’t know what to do with it so I took lessons. After about eight weeks. I was getting tired of learning Chuck Berry riffs since that’s not what I wanted to do, but at least now I knew where to put my fingers to make weird sounds. So that’s when I went off to see what kind of strange noises I could make with this thing. That was when I began to meet some people in this class I was taking that conceptual artist Chris Burden started teaching in UCLA. He was hired to teach a class called New Forms And Concepts that was supposed to open people up to doing more than painting or sculpture. One of them was wearing an Ultravox shirt so I immediately was like, cool! I’ll talk to these guys! They told me they were in a band called Neef and that they were opening for The Urinals at the coffee house on campus next week. So I went to that show and thought it was really cool. The guys in Neef were pretty much self-taught and I could tell because they couldn’t play very well. So that’s when I thought, maybe they’ll let me play with them! So I asked them if they’d let me play with them the next time they got together and they said sure.

Those were the first guys I started playing with and we came up with some interesting stuff but they never wanted to rehearse anything; they always wanted to improvise. I kept thinking we had good stuff and if we practised it, we could get good at playing it. But they didn’t want to do that so that only lasted about six months. We decided to do our own record because our friends in The Urinals had done it and we realised how easy it was. So we all put in $40 and pressed up as many as we could for $200. That’s when I realised I could do this by myself. For the first Independent Project records, I decided I wanted to make a record as a fine art piece. This was my last year at UCLA and I was taking a silkscreen class, so I figured I could silkscreen on the record. I was making experimental films, so I thought to put a postcard insert with a still frame from one of my films. The first couple records I did were before I discovered the letterpress. So I was xeroxing sleeves and folding them, but still trying to make them art.

When I first began to take notice of Savage Republic records in used bins sometime in the early 90s, it was at a time when many American punk labels like Gravity, Vermin Scum and Unleaded were doing silkscreened covers, rubber-stamped labels and giving their releases a very intimate and personal touch. Since you were doing it ten years prior to those labels, I’d like to know where you found the inspiration.

That came from being an art student and trying to figure out what I wanted to do for my art. As an undergraduate, I was doing painting, drawing and sculpture and I had fun with it, but I knew I wanted to do something different. I always felt if someone else is doing it, I don’t want to do it. I wanted to forge my own path. I loved music and records, so I decided to make a record that was fine art. I wanted people to discover art in the real world. They shouldn’t have to go to a gallery or a rarefied space to find art. It was art for the people!

So from Neef and the first few 7"s you released on Independent Project Records, where did the idea for Savage Republic come about?

I stuck around UCLA for another year after graduating and the first few singles that were released on Independent Project. I got a job on campus as a courier. By that time, I had met a few other guys I ended up doing music with. One of the guys in Them Rhythm Ants, which was the third IPR release said, ‘I’ve got this teenaged friend who is an amazing bass player and he wants to learn how to play experimental bass’. He was into jazz and hardcore punk. His name was Jeff Long who for a short amount of time was in the Los Angeles hardcore band called Wasted Youth.

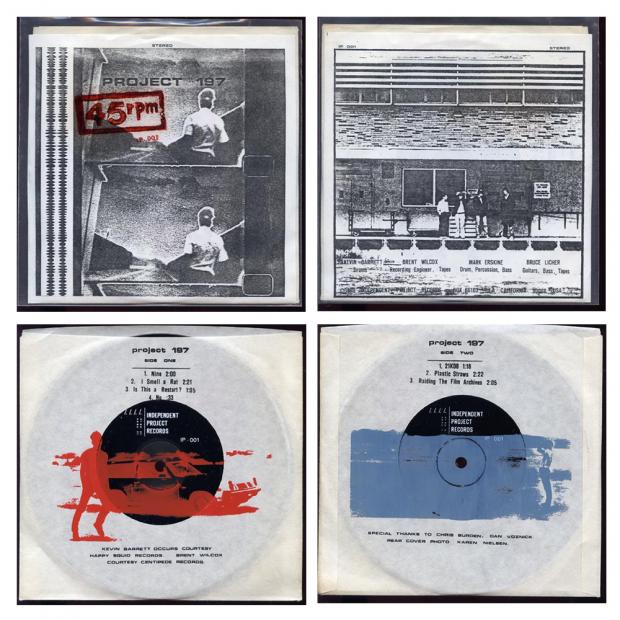

Project 197 7" EP cover and inner sleeve art by Bruce Licher, 1980

Yeah! I know them well!

Well I met him before he joined Wasted Youth. He was really into Jaco Pastorious, but he wanted to experiment some more, so we started jamming. I had done a student film in the subterranean utility tunnels under UCLA that I got permission to do. They loaned me a key and I still had it, so I thought it’d be cool to take our instruments into these tunnels and jam down there and see what we come up with. We were really excited. The first recording we did was on a boombox and I'm actually looking at the possibility of releasing that material soon. We brought down two basses, a fuzz box, a funky drum kit and some scrap metal percussion.

The first two songs we ever jammed on down there ended up being the first two songs on the Savage Republic debut album Tragic Figures after some development. Then a couple of months later I saw a flier for a Glenn Branca performance. It might have been his first LA appearance at CalArts, an art school north of Los Angeles in Valencia. I went out to see that and it blew my mind. For the first ten minutes they were tuning their guitars and I remember thinking it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever heard! I started hearing things I couldn’t see the people on stage playing. The tones were bouncing around! I went up to talk to them afterwards and saw they were playing guitars that were unison tuned and I was like, I’m doing that! So at our next rehearsal, I took my electric guitar and put all B strings on it and we all played in B and that’s how we came up with the Savage Republic song “Exodus”. Again, more no wave New York influence there!

Your mention of Wasted Youth is a perfect segue into my next question. By the time Savage Republic got to the point of playing gigs, was there already a bubble within the LA punk scene where an experimental punk band could fit in?

Yes. A lot of it was centred around this little downtown club called The Brave Dog. We had a friend Jonathan Gold who started off as a musician I knew from UCLA and became a Pulitzer prize winning food writer for LA Times. He passed away a year or two ago and there’s a documentary about him. But when I met him, he was playing amplified cello for a band called Overman who never recorded anything. He offered the project I was doing in the tunnels called Bridge a chance to open for Overman at Joey Kill’s Bar & Grill.

I kept in touch with Jonathan and there was a little art gallery just west of downtown that he was putting on music shows at. We had booked a show that was going to be the last show for Bridge and the first show for Africa Corps, which became Savage Republic. A week beforehand, the gallery closed. We had already put up fliers and didn’t know what we were going to do until somebody said we should check out The Brave Dog. So we ended up renting out The Brave Dog for $100 and moving the show there and it went well. We brought in $102 at the door, so we didn’t lose money!

The couple who owned The Brave Dog really liked what we were doing, so they invited us back and we put on shows with Kommunity FK, and there was another band called Aphotic Culture who were really interesting. That’s how we got started and I had another friend from UCLA who was singing in a band called Afterimage, they were post-punk and Joy Division influenced but had a saxophone. We would end up opening up for them at the bottom of the bill. When Tragic Figures came out, we started getting more attention, but what really kicked it up a notch was when we got the opportunity to open for Public Image Limited.

Yes, you got to make those nice letterpress postcards for the gig.

Exactly! I had met the people who promoted the gig. They really liked what I was doing with Savage Republic, so they hired me to make the postcards and the tickets. But the whole thing of how I ended up finding out about the letterpresses coincided with us deciding no one was buying singles anymore and we needed to record an album. Through my job at UCLA, I found out about this offset lithography class being offered at night. I went to the first one and there weren't enough people who signed up for it so it got cancelled. Then the teacher told me there was a letterpress class that was taught through the Women’s Graphic Center. So I signed up for that instead.

Savage Republic Tragic Figures cover art by Bruce Licher, 1982

In that class, I created a postcard for the upcoming Africa Corps album and then I saw this big flatbed press that had a 18" x 24" bed and I thought, ph! That’s just the right size for an album jacket! So I asked the teacher if I took the class again if she’d teach me how to print on that press. She said sure, so that’s how that cover came about.

How much of the Independent Project Record packaging was made on that particular letterpress you were taught on?

I did stuff on that for about a year and a half. I did the Kommunity FK album The Vision And The Voice there and they weren’t too pleased to see that on their drying racks! [The artwork features various sexual acts occurring in a mountain landscape] It was a women’s building and they didn’t appreciate it. Up until the end of 83, everything was done at the Women's Graphic Center at Woman’s Building in downtown Los Angeles, but it got to a point where people were asking me to print album jackets for them. For the Happy Squid label, I did the 100 Flowers Drawing Fire 12", and the God And The State album [Ruins: The Complete Works Of God And The State] and I did stuff for the band 17 Pygmies. That’s when it was reaching a point where I needed to get my own equipment. Fortunately I got a loan from a friend who – unfortunately – was in a car accident and was paralysed and got a big settlement. It was also a time when a lot of printers were getting rid of their letterpress equipment. So I got some equipment and rented out a cheap warehouse downtown. The Party Boys album was the first one we did in the new space on new equipment.

Besides things from the LA punk scene, what were some of the other record packaging you were asked to make at this time?

One of the guys in the band Fourwaycross who I ended up working with later on was a graphic designer at Warner Brothers Records in the 80s and told me I should bring my portfolio in there. So I ended up taking a meeting with them and they really seemed to like my stuff and kept saying, ‘Jeff should see this’. After that, they all went back to work and I was sitting there thinking, when is this Jeff guy showing up? It ended up being Jeff Ayeroff, who was the creative director at Warner Brothers at the time and he ended up giving me the biggest job I ever got designing promotional sleeves and posters for Scritti Politti and their song “Perfect Way”. That led into more projects with Jeff Ayeroff and then some of those designers went onto other labels so from that, I ended up doing a lot of work for major labels in the late 80s.

When did it hit a point where you needed more equipment to get more work done?

Probably around that same time. I was operating with two presses for awhile. and then maybe around 1990 I was offered a large Vandercook press and we started making posters with that 26" x 30" bed. We don’t have it anymore, it was being problematic so we ended up donating to a university in Arizona.

How did you get on the radar of REM to do artwork for them?

I think it was 1989 when I got a call from the REM offices hiring me to print a Christmas card for them. Two years later, they came back and told me they wanted me to design and print the entire fan club package for them this year. They got such a good response that I ended up doing that for them for about ten years. I found out later Peter Buck was a huge Independent Project and Savage Republic fan. Someone who went to his house once told me he had an entire wall of his house dedicated to Independent Project Records. That was a great gig that sustained us for a number of years. It would keep us busy for three months out of the year and it would pay for half of our expenses every year.

I’m curious how the relationship with the UK duo Woo came about.

I was friends with one of the head people at Rough Trade distribution in San Francisco. They were starting to put out records and they were asking to put out the second Savage Republic album at one point. I would go up there to deliver records to them and he’d allow me to dig through the back of their warehouse. I found a copy of that first Woo album. It looked interesting so I brought it back with me. I got home and listened to it and I loved it. There was an address on the back, so I wrote them asking if they had any other music available. I got a package back with a tape in it with a letter that read something like, ‘We don’t have anything else out. Would you like to put this out? It’s our next album’, and it was It’s Cosy Inside. That’s how that started. It’s funny you bring them up because the other day I found a polaroid of Mark Ives from Woo. He came out and stayed with us a few weeks. It’s me and him standing in front of my vehicle with a dog. I have no idea whose dog it was. When Savage Republic toured Europe in 1988 they let us stay at their house in Wimbledon. It was the family house where they recorded. It was empty and we got to stay there. They had gear upstairs and we jammed on Woo’s gear.

What happened with Savage Republic after the release of the debut album?

Savage Republic split apart when we were recording our second album. There was a difference of opinion on direction. I ended up keeping the name and the drummer Mark Erskine stayed with me. The other two members were Phil Drucker and Robert Loveless. Most of the songs we started recording were based on ideas they had come up with and it was a really different direction. That album ended up being finished up as the 17 Pygmies album Jedda By The Sea. Mark and I play on half that album. Those songs were finished up in a way that I wouldn’t have finished them, but it is what it is. The first thing we did as Savage Republic with new members was the Trudge EP that was released on Play It Again Sam. To me, that’s the direction I wanted to go in. The idea of a soundtrack for your mind type thing. Robert Loveless rejoined and we worked on the Ceremonial album. That album ended up coming out way more cleaner than I wanted. I also wanted it to be instrumental. Most of the other band members wanted vocals, so I just said, OK, whatever. I think it worked better as an instrumental album.

I was listening to some of the vocal tracks from the record the other day because we are looking into reissuing it in an extended version. Some of it is not bad, but some of it makes me cringe. But again, it is what it is. But the reason we went to that studio and got that super clean sound is I had met Abecedarians and Drowning Pool, who we worked with on the Independent Project side label Nate Starkman & Son. They were coming up with some great sounding recordings at this studio, so I figured we’d go in there and make this amazing sounding record. Unfortunately, what we didn’t realise was you have to have really good gear when you go into a nice studio. That didn’t occur to us! We had shit gear and we went in and it wasn’t right.

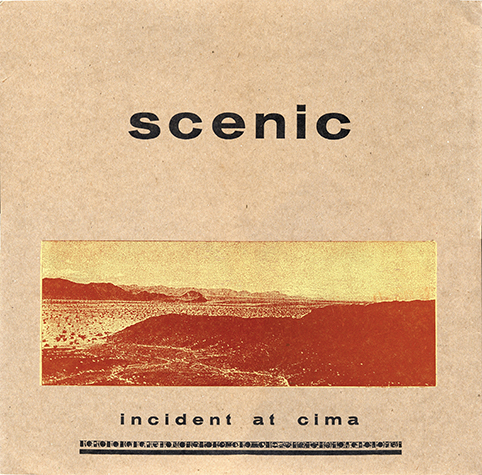

Scenic Incident At Cima cover art by Bruce Licher, 1995

What was the motivation behind the shift from the rather abrasive sounds of Savage Republic to the more serene sounds of your next project Scenic?

That whole Ceremonial experience made me give up trying to lead the band and let it become a more collaborative effort. Then it hit a point after our album Jamahiriya where I just didn’t want to do it anymore. This was not the direction I wanted to go in and the people I brought in to be members were fans of Tragic Figures and wanted more of that. They didn’t understand I had already done that and wanted to move on and do something different. So that’s where Scenic came from. I wanted a band where I was directing what we’re doing. And that worked for a while, but then it turned into a collaborative thing again and that’s one of the reasons Scenic stopped.

Have you ever thought of just doing a solo album?

I’ve demoed two different solo albums and never got around to finishing them. One of these days...

Have you ever been approached with a printing project for Independent Projects that was just totally impossible to pull off?

We get approached with ideas all the time from people who don’t realise how much their concept would cost to print, but I can’t think of anything I turned down. I was always trying to do things differently than how they were normally done in printing. A lot of times I’d run up against people who had more experience than me who would say it was impossible and sometimes I would pull it off and sometimes it’d fail miserably. The Party Boys record for example has something like 100 different colour variants. A friend of mine just started a Facebook group where anyone who has a copy of the Party Boys record can send a picture and it’ll go up. That was an interesting experience that for the most part really worked. Some of the covers look pretty bad, but overall as a conceptual experiment it really worked. The reason a lot of the covers are bad is because I let the band members come in and run a lot of them and they never had used a printing press before. There’s a lot of them that are off-register or they over-linked the image. Again it is what it is.

How has the label and operation grown from that point in the 90s when you were doing things for REM and major labels? Where is it today?

It had grown to its largest level during the 90s. I had people working in the shop and was constantly busy. After 2000, I couldn’t sustain doing the label anymore because the way I was choosing to do it was not feasible financially. I had been trying a lot of different ways to get distribution deals and it hit a point where I had to concentrate on what was making me money rather than my art. There were a few things I got to work on like the Springhouse CD and the Red Temple Spirits three disc set but that point was when the label died down. We were operating in Arizona at the time and my wife wanted to move back out to California and work on paintings of the eastern Sierras. So I downsized the operation to where it was just me and we moved back.

When we first moved here to Bishop where we found a big house with an oversized insulated garage, so we just worked out of the garage from home for a few years. After the 2008 housing crisis, the fellow who owned that house ended up losing it to the bank, so we got forced out since we weren’t in the position to purchase it. We found this place in town where I currently have the print shop and it's the best space I've ever had. I’ve moved this print shop five times since I first started it up so I’m not looking to move it again.

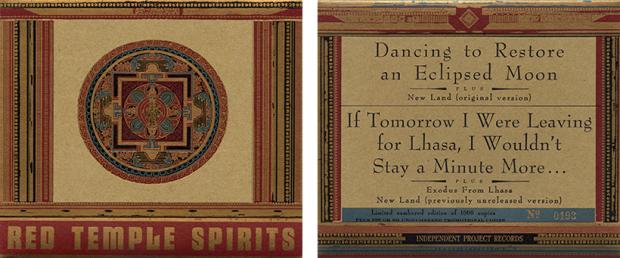

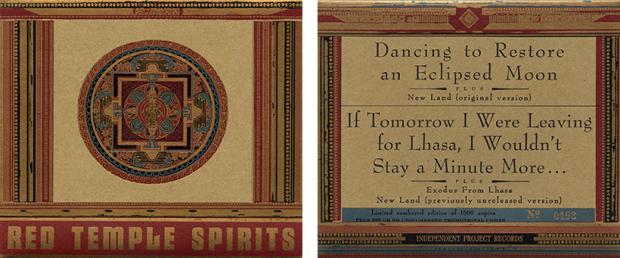

Red Temple Spirits 3CD compilation cover art front (left) and back, by Bruce Licher, 2013

Where did the idea to put together the Savage Impressions book come from?

I always thought it’d be nice to have a book of my work, but it wasn’t something I could put into motion. I got approached by Richard Kegler of P22 about three years ago. He was a fan and a subscriber to our 10" archive series I did in the early 90s. He got into letterpress largely because of my work. He was at a letterpress conference and met up with a fellow from England who was also a fan who asked, ‘Why isn’t there a book of Bruce’s work?’ So Richard got in touch and asked if I would be interested in having a book about my work published to which I responded, ‘Uh, yeah!’ He ran a Kickstarter campaign to get it to happen.

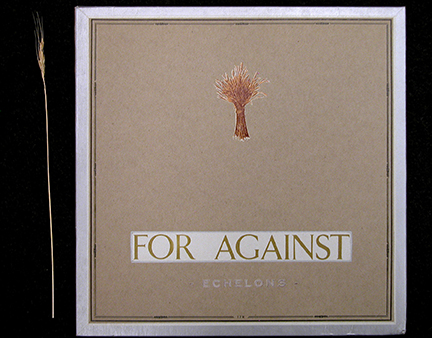

For Against Echelons cover art by Bruce Licher, 1987

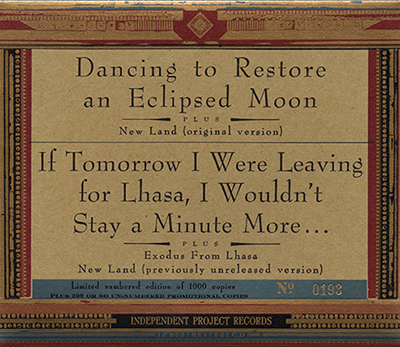

Once we realised it was going to happen I got to go through my archives and the project expanded from there. When I was printing the For Against cover that was nominated for a Grammy, I remember running that through the press 15 times and figuring out I wasn’t going to make any money off of it. So, I figured if we were going to make this book, it would have to be expanded to make some money. It grew from originally 150 pages to 240 after finding more stuff. That’s the reason it’s not available through Amazon. He has to make his money back. There are a lot of people in Europe who want it but it’s a heavy book that costs a lot of money to send over. So we’ve been talking to a UK publisher about potentially doing another edition over there.

And how did the reissue campaign of Independent Project Records come about through Darla?

That got spurred along by the book a bit. I was helping Stuart Swezey with his Desolation Center documentary by doing some printing for him. When he was doing the festival circuit with the film, he was dealing with our old friend Jeff Clark who was in the band Shiva Burlesque. Most of the members went on to be in Grant Lee Buffalo. Jeff had moved to Nevada City, California, bought an old theatre and started doing a little film festival there. When Desolation Center was shown at the festival, Stuart couldn’t make it, so I went to represent the film. I got reconnected with Jeff and he told me he had some money and would like to reissue a few things from the label.

Once Jeff got the book in his hands, he really wanted to start reissuing stuff. One of the things going into production now is an expanded reissue of the album by Half String, a shoegaze band from Arizona I worked with in the 90s. They broke up right after the CD came out, so we didn’t do much with it. The album has been out of print for years and they found a bunch of unreleased recordings from that time so we’ll expand it and release it. Jeff is working on the second Shiva Burlesque album with demo tracks. We’re doing the first Scenic album and just trying to get an interesting schedule of releases together.

You stay busy!

Too busy sometimes! But it’s nice to finally refocus my attention on the record label since that was the reason I set up the print shop in the first place before all these outside things took over.

_ _ _

Bruce Licher and Independent Project Records playlist

Project 197

“Nine”

From Project 197 (1980)

The first release on IPR consisting of Licher with Urinals drummer Kevin Barrett and future Savage Republic member Mark Erskine sets the stage for the dark and atmospheric sounds he would become known for and is adorned with photocopied covers and silk screened labels.

Bridge

“Assault On Base 4” (1980)

Recorded in the utility tunnels that run underneath the UCLA campus, the duo of Licher and bassist Chez Voz manage to reflect their surroundings in creating a din that is dark, cavernous, and somewhat frightening.

Savage Republic

“Flesh That Walks”

From Tragic Figures (1982)

The debut album from Bruce’s first band not only contains some of the more challenging music to come out of the American punk scene in the era, but also is the premier of his use of the flatbed letterpress IPR would become most well known for.

Kommunity FK

“Anti-Pop”

From The Vision And The Voice (1983)

Wrapped in a pretty shocking package, the debut album by the LA godfathers of deathrock is just as disturbing and provocative as the music contained within.

For Against

“Shine”

From Echelons (1987)

Releasing the first album by this Nebraska based post-punk band might have been one of LIcher’s smartest moves. Not only was it one of the label’s most successful releases, but it got him a nomination for best record packaging at the 1988 Grammys.

Scenic

“Carrying On To Cadiz”

From Incident At Cima (1995)

Moving to Sedona, Arizona and leaving Savage Republic behind, Licher’s late 1990s project Scenic expanded on his concept of ‘soundtracks for the mind’ in both sound and presentation.

Woo

“Water Drum”

From It’s Cosy Inside (1989)

After discovering their self-released debut album in a California record warehouse, Licher became a huge proponent of this brotherly duo and released their second album It's Cosy Inside and this oddly soothing track "Water Drum".

Savage Republic

“Kill The Fascists!”

From Recordings For Live Performances 1981–1983

With such a striking title, it's obvious why this track would be one of the best known in Savage Republic's repertoire. But this early live recording of the song displays the spite and anger the band ran on in the early days prior to their more refined sound of the later 1980s.

Shiva Burlesque

“Who Is The Mona Lisa”

From Mercury Blues (1990)

Moody and atmospheric, Los Angeles’s Shiva Burlesque shared many of the same qualities as Savage Republic but their ability to craft a perfectly brooding pop song was all their own as proven by this track.

Half String

“Shell Life”

From A Fascination With Heights (1996)

Licher’s artwork (initial concept and layout by Half String singer Brandon Capps) with this underrated US shoegaze band is some of his best and displays how well he adapted to working with the CD format.

Jeffrey Clark

“Exploded View”

From Sheer Golden Hooks (1996)

The wildly eclectic debut solo album by Shiva Burlesque's frontman and Licher’s Independent Project Press partner Jeffrey Clark was crammed with spoken word pieces, delay-drenched guitar work, and its share of baroque pop, like this track.

Bruce Licher

“Owens Valley Driving Music, Part 4: Lower Rock Creek Road”

From Owens Valley Driving Music (2018)

Still inspired by the vast swaths of land to be found around the Mojave Desert, these more recent recordings find Licher out in the pristine Owens Valley with his guitar and remote rig creating a hypnotic sprawl of krautrock-like sound.

Savage Republic are featured in The Wire 58/59, (New Year 1989); Scenic are in The Wire 152 (October 1996); LTM Recordings founder James Nice wrote about Savage Republic’s debut album Tragic Figures in The Inner Sleeve (The Wire 352, June 2013); Savage Impressions: An Aesthetic Expedition Through The Archives Of Independent Project Records & Press is published by P22 Publications

Comments

Hi,

In the early '90s I run the radio program 'Música marginal' in which, thanks to Bruce Licher who frequently sent me his releases, I was able to broadcast the Independent Project records.

This interview makes me happy because it reveals the importance that this label have in the independent music.

Guillermo Escudero

Leave a comment