Tooth and nail: an interview with Pavla Jonsson

October 2021

Miloš Hroch talks to the first riot grrrl in communist-era Czechoslovakia

“Girls are sitting in silence, with their big plans, which will turn into nothing”, sang Dybbuk’s Pavla Jonsson in the 1980s, “But to hell with it all, anyway”. Called “Ale Čert To Vem” (“But To Hell With It All, Anyway”), the song addressed the stereotypical roles imposed on women, either by family or society. It was exceptional for Dybbuk´s lyrics, which were more commonly attuned to the beatnik-dada-fairytales or poetics of the everyday. In sum, a rare moment when alternative rock in the former Soviet satellite state intersected with feminism. Even if it went against type, the song made the now 60 year old guitarist and singer Czechoslovakia’s first riot grrrl.

In 1980 Jonsson and her two friends co-founded the band Plyn (in English, The Gas), who were soon put on the blacklist by the communist cultural commission. After changing their name to Dybbuk, they released their older songs on several compilations such as 1986’s Czechs: Till Now You Were Alone (as The Gaz) on the Italian label Old Café Europa. In 1987 Dybbuk even had an semi-official release by the state-owned company Panton in the Rock Debut series. The constant confusion resulting from bands changing their names was part of the “socialist rock folkore” back then. It also served as a form of protecting the identities of the musicians involved. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, which saw communist Czechoslovakia’s transition to democracy, Dybbuk released the 1991 compilation Ale Čert To Vem (But To Hell With It All, Anyway) and reformed, this time as Zuby Nehty (Tooth And Nail), in which Jonsson is still a member to this day.

Due to the information barriers erected during communist Czechoslovakia, back then Jonsson didn’t know about bands such X-Ray Spex, Raincoats or Slits, alongside whom Dybbuk featured in Vivien Goldman’s 2019 book Revenge Of The She-Punks. “I guess it was the zeitgeist,” she observes in the following interview. After 1989, Jonsson continued as a feminist scholar – she specialises in gender and subcultures at the Anglo-American university in Prague (indeed, she was among the first to teach gender courses at Czech universities). In her 2017 book Women, Music, Creativity: From Hildegard To Cosey Fanni Tutti (2017), Jonsson explores the contribution of women to rock music – as ever, based on her first-hand experiences.

Miloš Hroch: How did the formation of your band Plyn come about?

Pavla Jonsson: My friend Hana Kubíčková (later Řepová) attended the same grammar school, and we spent all our free time together. At that time, we went to concerts organised by the Jazz Section. After Charter 77 [the human rights manifesto and open letter written by a group of dissidents who criticised the communist government after the political trial with underground group Plastic People Of The Underground and their peers] we frequently visited the secret house concerts of protest singers like Jaroslav Hutka or Svatopluk Karásek. I also loved progressive rock, Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Velvet Underground, Zappa and Kraftwerk. I had a few records from my parents’ friends in Norway, and at the black vinyl market in the Prague quarter of Letná, I exchanged one record for another every week. I discovered punk quite late in 1980, and I was obsessed with The Clash and their double vinyl London Calling. I learned to play the electric guitar according to The Ramones.

Hanka and I used to go to the Cinema Club for lectures on Fellini, Bergman, the Czech New Wave, etc. One day in 1980, we were on our way from the cinema – with everything above experienced and listened to – and I asked what we should listen to now. Hanka clairvoyantly replied: “Plyn”. It was a joke, but we had a name for the band. Our lyrics were comical and full of love. One early song was called: “The Strongest LSD Is Love”.

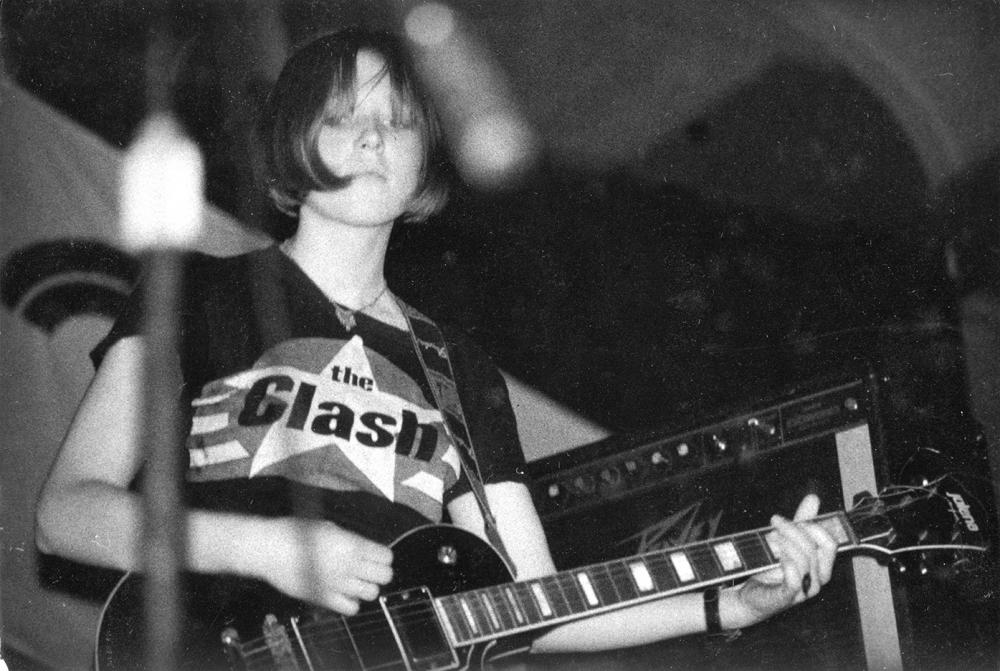

Pavla Jonsson, 1980s. Photo: Prague Popmuseum

Then other players joined. How did you meet later vocalist, pianist and bass guitarist Marka Míková, a famous children’s actress at that time?

I don’t have the gift of singing, nor did I know how to play anything extra. I just contributed ideas. But Tomáš Míka, a classmate from the grammar school, today a Czech poet, brought his future wife Marka (then Horáková) to us. She played the leading role in Václav Vorlíček’s fairytale How To Wake Up Princesses from 1977, and she received hundreds of letters from fans.

Without Marka’s talent and expressive power, our airship would not have been able to soar. We used to rehearse in our flats, and all our parents supported us. With the money I earned from hop harvesting brigades [students were sent to summer brigades as a form of agriculture aid in socialist Czechoslovakia], I bought a Czech electric guitar Jolana Galaxis. I amplified it through the multitrack miracle of the Tesla B730 company' Marka played the piano; Hanka pounded on paper boxes, later she got a real drum set. In the beginning, Renata Špičanová, whom I met during the hop harvesting brigade, started to play the saxophone in our bands. She began her studies of ethnology and set the sociological tone of our poetics. “Girls, I saw a lady with heavy earrings,” she mentioned at one rehearsal. So I played chords à la Ramones and Marka sang, and this is how we made our song “Paní I” (“Mrs 1”), which also appeared on the post-1989 anthology. “The lady has heavy earrings, a heavy chain around her neck if the lady even hears if the lady swallows. She does not hear or swallow...”, and then another song “Paní II” again: “The lady is sitting on the ice and staring on and on, she is not waiting for anyone”. We were asking ourselves, is this what we are going to grow into?

Can you remember your first concert?

It was at one of the student clubs called Euridika in Prague, the spring of 1981. This building was demolished a few months ago. The opening act was Misha Glenny with his music project, our British friend became a BBC star and a famous journalist. He studied in Prague. Part of the audience was genuinely horrified by our impudence.

Did you realise that you were doing something radical within the alternative scene, where women were almost invisible?

It didn’t seem weird at all to play only with girls. I didn’t fully realise that until music journalists began asking us strange questions. For example, if our husbands gave us the permission to play this music, and if we shouldn’t let the nonsense go when we have children, and whether we understood that it’s not normal otherwise. Our second concert took place in the now famous punk club 007 at Strahov. Ivo Pospíšil from the band Garáž invited us, and then he had big problems because we didn’t have permission to play publicly. The audience shouted at us, “Bring the grain” (as in, for the hens). So we got angry and played with all our might – and we could see that they treated us – girls – differently.

I naturally tended to the scene around Jazzová Sekce (the Jazz Section) and to people like Mikoláš Chadima [of Extempore, MCH Band, etc]. In the autumn of 1983, at the festival in Ostrov nad Ohří, Mikoláš asked us if we had some demo. We admired Chadima, partly because he cared about the public interest, he spread the samizdats of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and he released tapes on his Fist Records. We immediately gave him a demo tape we recorded on a four-track recorder at the cottage in Milevsko that year.

A year later, Chadima handed me an actual compilation record released by the Italian label Old Café Europa called Czech: Till Now You Were Alone. They chose the song I wrote, “Kilgore Trout”. It was inspired by the character of a crazy writer from Kurt Vonnegut’s novels. It is a funny song about the meaning of life. During the 1980s, Vonnegut visited Czechoslovakia as a guest of the American Embassy and met some of the cultural figures under pressure from the regime. One of our fans played the song to him back then.

Were you aware of bands like X-Ray Spex, Raincoats, or The Slits bringing a feminine perspective to punk?

We had no idea. Ivan Martin Jirous from Plastic People Of The Universe said that the most significant damage the communist regime had done to the young generation was an information blockade. It was even more true of women. Little did we know that bands so similar to ours were being formed both in the West and in the former Eastern bloc. A new field of gender studies and feminist theory at universities deals with various aspects of women’s existence. Simon Frith, for example, sees this time as a historically revolutionary entry of women into the scene, and this may have been the case on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Punk opened up the possibility that rock could be against sexism. The singer became a subject, not an object.

It’s shocking how our Plyn was strikingly similar to The Slits and The Raincoats in the early stages, and this is something I observed later on in the 1990s when I had a chance to listen to them. It was a similar simplicity, girlish voices, craziness of ideas, and intuitive play on instruments. With Plyn, I also rejected the traditional concept of femininity known from the mainstream. We performed without make-up, in ordinary T-shirts and trousers or, sometimes, in home-dyed duvets. I guess it was the zeitgeist.

Since when did you start reflecting feminism in music?

The girls in the band were never interested in feminism. We always argued. My ‘enlightenment’ came in 1983 when I worked at the Summer School of Slavic Studies at our Faculty of Philosophy at Charles University, where I studied. One 120 Czech studies scholars from all over the world came. My job as a student was to take care of the American group, but we had parties with everyone in the evenings at the dorm. Many of them became lifelong friends. They kept sending me feminist books by Betty Friedan or Gloria Stein, or The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer, which I translated into Czech in 2000 – it drew my attention to language and topics, which gave me a whole new perspective and vocabulary. The most exciting thing at their universities were the feminist studies. Until the morning, we used to discuss the formation of the family, school, media. We chatted about the cause of wars, about the sexual revolution, about pornography and about prostitution.

In 1983, the party's weekly Tribuna published an article “New Wave With An Old Content”, which influenced the entire alternative scene. The text was full of nonsense, misinterpretations and it presented new wave and punk as a Western propaganda tool. How did it affect you?

Our band Plyn got blacklisted. In the city of Kladno, we had to pass the exams before the communist commission. At that time, every band had to attend such a process to get permission to play publicly. We already thought we had the license in our pocket. But then the head of the commission called me to say that she had read our texts in detail and wanted to drink a bottle of wine and jump off the bridge. I tried to explain to her that there are different conceptions of beauty, such as Baudelaire’s dark poems. She concluded that writing depressing things is easy, but writing something optimistic is a hard job. And we didn’t pass the exam. Immediately after this experience, my co-player Marka Míková wrote the song “Radujme See A Buďme Šťastní” (“Let's Rejoice And Let's Be Merry”), which was meant partly seriously, but at the same time ironically. We had to change our name to Dybbuk and then tried the exams in Prague, where the there was a brave sympathiser of us. I then went to all the debates that concerned the article “New Wave With An Old Content”. Later the music journalist Josef Vlček responded to that new wave article and corrected the errors – like that The Clash and other punk bands were actually working class.

What was the change after the revolution?

The change was so euphoric. First, we recorded the old songs of Dybbuk which came on the LP called Ale Čert To Vem (To Hell With It, Anyway). Then in 1993, as Zuby Nehty (Tooth And Nail), we signed a contract with the major label Bonton. It was like in the movie, we were sitting in leather chairs, champagne was flowing, and we got paid for our record. Over 5000 copies were sold, but Bonton did not want to continue with us. That’s how it was: for a moment, in the early 1990s, international companies and labels wanted, for a short period, to monetise Havel’s independent culture after the Velvet Revolution. Instead, alternative labels were created, and we took refuge under the wings of Indies Records. Mainstream and normalisation era pop has returned to big labels. It was dizzying and a big boost, but then it faded, and we returned to the edge where we belonged. This was also well seen on tour in Germany, on which we went in the 1990s, and we gradually moved from culture houses and hotels to squats and sleeping bags.

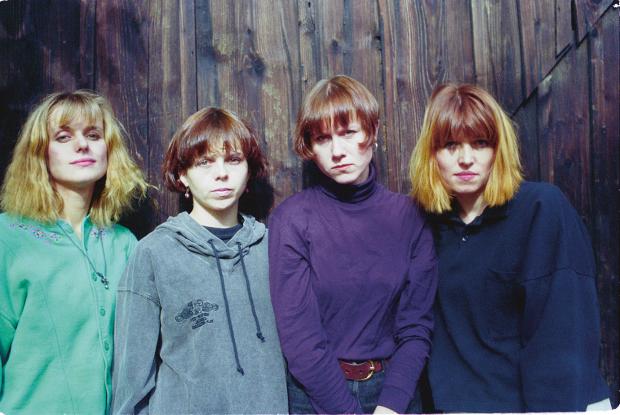

Zuby Nehty, 1991: (from left) Marka Míková, Hana Řepová, Kateřina Jiříčková, Pavla Jonsson. Photo: Jiří Volek

Wire subscribers can read more about the alternativa scene and Mikolas Chadima in Miloš’s Once Upon A Time In Prague piece in The Wire 451 via the online archive.

Comments

Hi from Czech,

Absolutely perfect interview, article, thanks for sharing and its creation.

I was lucky and I know Pavla personally, in the nineties I saw Her live, an unforgettable thing She and the band Zuby Nehty!

She is ...Beautiful Rebel.

Luboš

Leave a comment