Charles Tolliver remembers Max Roach

November 2024

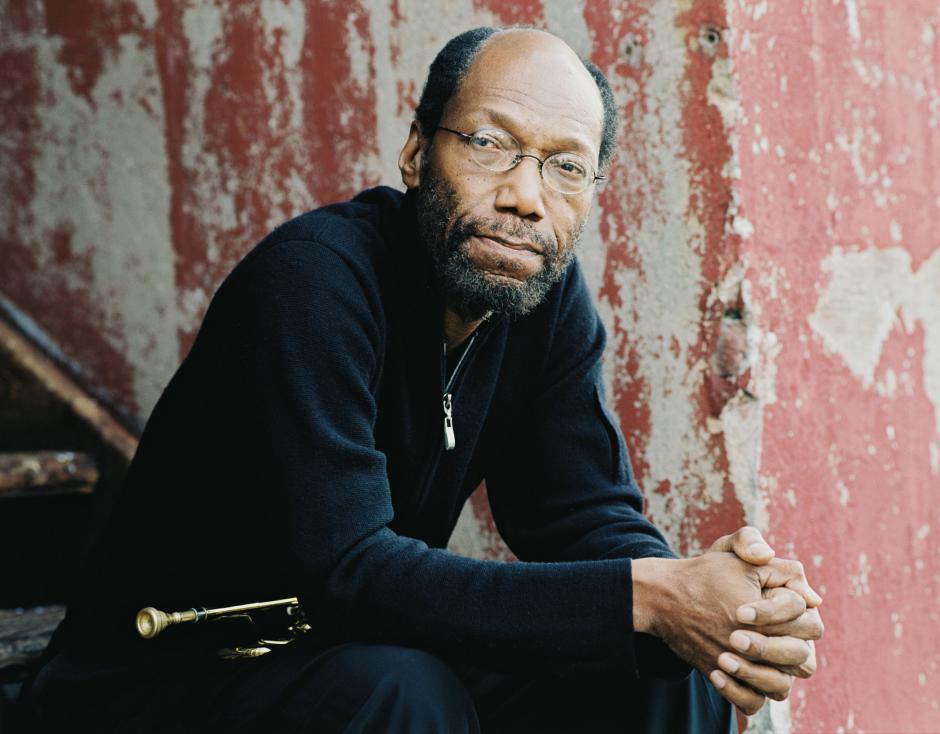

Charles Tolliver. Photo by Jimmy Katz

Ahead of his celebration of Max Roach, trumpeter Charles Tolliver talks to Gabriel Bristow about playing alongside the legendary drummer, studying at Howard University with Donny Hathaway and Stokely Carmichael, and the legacy of Strata-East Records

Gabriel Bristow: You played alongside Max Roach when you were a young man. What was he like to play with? What influence did he have on you musically or otherwise?

Charles Tolliver: Max Roach was a big hero to us kids at the time. He had that regalness about him. But at the same time, if you got the chance to meet him in person, you had to understand the way this regalness met with the explosion and precision of his drumming. Whenever he would be playing somewhere in New York I would go and check him out. I had a chance to meet him and I basically said to him, if you’re ever looking for a new trumpet player, think about me. And about a year later [in 1967], I got the call. That started a relationship that stretched until his passing [in 2007].

In 1971, Roach asked you to create a drum suite adaptation of an old spiritual “Singin’ Wid a Sword In My Hand” from James Weldon Johnson’s Book Of American Negro Spirituals. What are your memories of that process?

Max said he wanted to do a kind of suite based on James Weldon Johnson’s book of negro spirituals. At the same time, my son’s mother – we were dating at the time – had a small storefront living space in the eastern part of Amsterdam, near the original Ajax soccer stadium. I was about to go and stay there for a bit. Before I left New York, Max and I sat down and mapped out the sections, what he wanted to do. When I got to Amsterdam I sat down to create it, and I think it took me about two or three months. Then I went back to New York and got the music printed up, and then off to [the 1971] Montreux [Jazz Festival] we went.

Who were your favourite trumpeters growing up? Who are your favourites now?

That’s kind of hard! My first trumpet hero was Charlie Shavers off of Norman Granz’s Jazz At The Philharmonic – the originals. My folks had those on vinyl. They would be worth a fortune now. I can picture that booklet of 78s. Charlie Shavers was featured on some of them.

And then of course there was Dizzy Gillespie, Roy Eldridge, Howard McGhee... But as I did my homework on the trumpet greats as a teenager, I came to love all of those guys because they all had something to contribute. There wasn’t one specific one, excepting Clifford Brown. He is very special. He occupies a place totally to himself.

And then of course there are all the people that came up just before I broke in: Lee Morgan, Donald Byrd, Freddie Hubbard. But there are other trumpet players that people don’t talk about – great trumpet players. Idrees Sulieman, Joe Gordon, and Art Farmer of course. As a matter of fact, I never heard Art Farmer ever miss a note. He played exactly what he wanted to play and he never missed. I mean not even half of a note.

And there was a British trumpeter that was coming up in my era: Kenny Wheeler! When I first came to London with Max Roach to play at a brand new Ronnie Scott’s, Kenny Wheeler would come there every night. We became friends. I brought my groups back to Ronnie’s over the years and we’d keep in touch. That guy could play, man.

You studied pharmacy at Howard University – the same university as the likes of Donny Hathaway and Stokely Carmichael. Tell me about your time there.

There is a freshman class picture with literally hundreds of students in it, and after carefully looking I was able to find myself, Stokely Carmichael and Donny Hathaway. I never ran into Donny Hathaway on campus. But I certainly encountered Stokely Carmichael because he was trying to recruit guys, and ladies too, to go down to Mississippi for SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Freedom Summer Project of 1964]. He was busy with that every day. So I got a chance to talk to him that way. But most of my time was spent in my pharmacy classes or hanging out in the fine arts building at the piano.

You started the Strata-East label with Stanley Cowell in 1971. Which releases are you most proud of?

All of the ones that still see the light of day! So you know, there were some 60 odd, and now there’s at least 40 actively in the market place. So any of those! I’m proud that they’re still being issued. I would say though that obviously the first LP that launched the label [Charles Tolliver’s Music Inc] would have to be my favourite.

Nowadays a lot of people use the term spiritual jazz. Strata-East is seen as one of the key spiritual jazz labels, but the term didn’t really exist in the 1970s. What do you think about the term now?

Well, I believe that it was you Brits that started that! [Laughs] The Soul Jazz record company were gung-ho on leasing music from us. They were paying attention. I think they were one of the first to coin spiritual jazz as it related to the sort of eclectic things that were coming out [in the 1960s and 1970s]. Because there wasn’t a particular style ascribed to what we were putting out. It was only what the artist-producer came with, and we agreed to put it out. So whatever flavour that was is what it was. But there are a number of what would be considered ‘spiritual’ offerings amongst the LPs that we put out, definitely. And that term has stuck and become synonymous with the label. It’s cool [chuckles].

I’m curious about the images of pyramids that you find in some of Strata-East’s promotional materials and record sleeves. Tell me about that.

Well, if you’re talking about the pyramids on the back of Clifford Jordan’s Glass Bead Games, he was speaking truth to power there with that. And a lot of the early success, straight into the present, was because of Clifford Jordan. After Stanley and I issued the first record he came to us and said that he had already started doing what we were doing, but he hadn’t gotten as far as manufacturing and merchandising the recordings that he had made. So he put the whole lot out with us. That was a very important addition.

Do you think musicians have a responsibility to raise their voices politically in the present?

If they’ve done homework on their instrument and what they’re offering to the public as an artist – if that’s spot on with what they’re trying to present – then if they also are political in their views, that’s OK. But I don’t want to hear it if they’re not even playing their instrument! [Laughs] Talk is cheap, you know. If you’re giving us something of your artistry that’s going to make an impact on this particular art form, then OK.

The only thing I would say is that musicians that mouth off about politics – they should never denigrate that which they wanted to belong to in the first place. You can be political, that’s fine. Just don’t denigrate the artform that gave you an audience. It shouldn’t be mocking for the sake of mocking. Right now we have the most dangerous mocking going on in the world. What’s going on here in America, that beats Boris! The counterpart here is far beyond that, and actually quite dangerous.

Charles Tolliver Celebrates Max Roach @ 100 is one of the EFG London Jazz Festival events taking place at London Barbican on 18 November, and at Brighton Dome on 19 November.

Comments

It was good content. It helped me a lot.

Oliver

Leave a comment