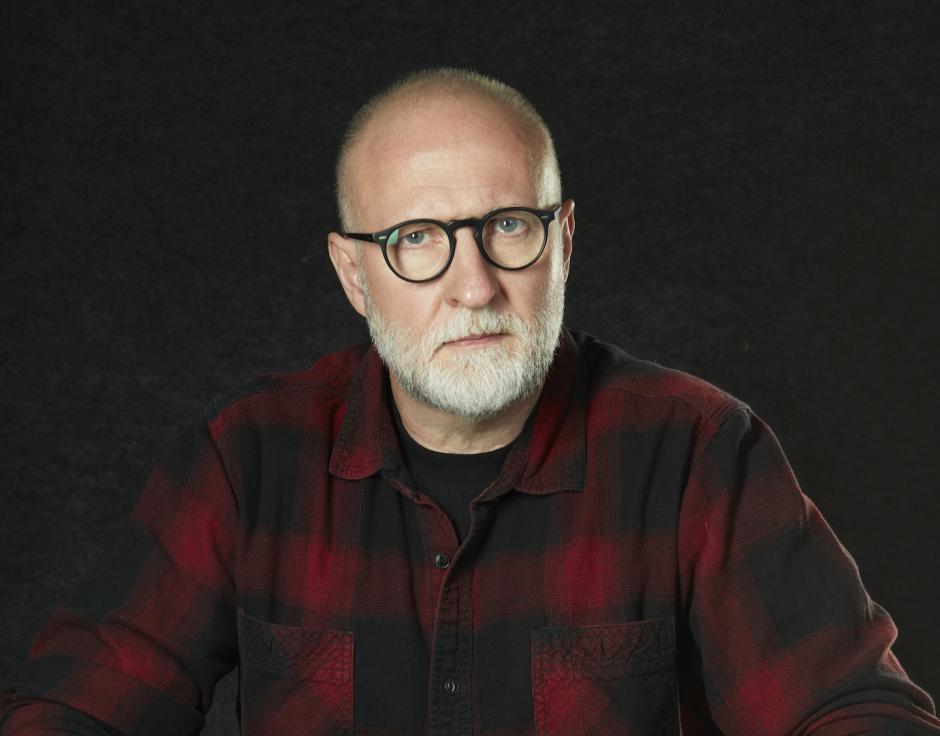

Heart on my sleeve: an interview with Bob Mould

December 2020

Bob Mould. Photo by Blake Little.

The Hüsker Dü, Sugar and solo veteran speaks to Stephanie Phillips about politics, isolation and stamina

Though you may not realise it, an unusual occurrence is taking place right now – Bob Mould is not on tour. As the frontman of 1980s punk pioneers Hüsker Dü and 90s trio Sugar, and a successful solo artist, Mould has spent his 40 year career in a cycle of writing, recording and touring the world. For the first time in a long time, he has stopped, just when he needed to be out there the most.

Mould’s recent 12th solo album Blue Hearts is his most politically charged work to date, addressing climate change (“Heart On My Sleeve”), the hypocrisy of the religious right (“Forecast Of Rain”) and the correlations between the Trump and Reagan governments (“American Crisis”). It’s followed closely by the 24 disc box set Distortion 1989–2019, which collects his entire solo output (aside from the new record) plus live tracks, collaborations and rarities.

When I interviewed Mould over the phone, he was in reflective mood at his home in San Francisco, sheltering from the worst of the wildfires that overcame the West Coast. The US elections were only a few weeks away at the time and given his album’s political heart, Mould was disappointed to not be on the road. “Once it felt like a protest record, it really became a protest record,” he explains. “Protest records are best delivered from the stage. It’s extra frustrating for me, but of course, it's my health and the health of the audience first. My live presentation is usually pretty sweaty and spitty so I'll be the last to go back to work at this point.”

Though it may be a while until Mould is back delivering his cathartic live shows, for now he’s happy to chat about his new record, becoming comfortable with his sexual identity, and why he feels he needs to speak out now.

Stephanie Phillips: Have you found it hard to be creative during this period?

Bob Mould: It feels harder. I have to give consideration to the fact that I'm sort of in campaign mode. You're talking about this very recent past that is a present thing for other people and that to me is always a little bit of a limbo time. I don't normally have a lot of creativity when I'm sort of filibustering my current ideas, but I do think the pandemic has exacerbated that. My process is I get really isolated and try to find it in myself. That's hard now because I feel distracted by the dystopia of it all.

There’s always that idea that artists are more creative in times of crisis. Is that something that seems impossible for you right now?

It's fuelled this current record that I have, but now that we're on the precipice of the election itself it's much harder as we get closer to the culmination of four years of insanity. It's really gotten to me, because of things like what was happening with Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, watching America heading towards that. Then, watching the government try to dismiss Black Lives Matter, it's not right. Being an old, gay white guy and remembering what the 1980s were like, that's a completely different type of marginalisation, but nonetheless it's that otherism that I thought we had gotten past. It's hard to watch, and trying to do the homework and be mindful and listen to other voices of other communities that are they're having struggles, it's a lot on a daily basis.

You mentioned that it reminds you of the political landscape of the 80s. Did you feel like there were things that you and others could do to kind of fight back against the Reagan government at the time?

Well, my personal story is I was born in a very small farm town in northern New York State. It was a very homogenous culture and not particularly enlightened. When I was 17, I moved to St Paul, Minnesota, I received an underprivileged scholarship to go to Macalester College. It was a very liberal school and it was an eye opener for me to enter this higher education community with people from all over the world, from all different cultures, and races and political persuasions.

There’s always a steep learning curve that we all have to go on sometimes.

Yeah. For me in my twenties I was sure of my sexuality, but didn’t have a sexual identity, so to speak, and I wasn’t integrated into the gay community. I was a punk rock kid in a van playing guitar all over the place. The punk rock scene that I was in was very tolerant, but it wasn't invisible in the community. It was OK to be gay if you weren't too gay.

Did that make you feel isolated?

I think it was a combination of that environment, but more importantly, it was a self-created problem of just not understanding what being gay was. I think the other piece of the puzzle would be that in the summer of 1981, with AIDS and HIV and this stigma that was applied to the gay community by the government, that was a heavy message for me to consider.

Did you ever feel there was a particular moment where you felt comfortable and part of a gay community?

When I left Minnesota and went to New York [in 1989] I sort of landed in Hoboken, New Jersey, and fell deeper into a music community where there was a lot of LGBT presence. There was also a lot of people dying. I guess maybe the way that it's portrayed on stage or in a movie is like, “Where's my favourite waiter?”, “Oh, he died last week, Didn't you hear?” That's when that started to become a weekly phenomenon and I understood the severity of it. That's when I started to do more and got more involved. It's one of my laments. I think about my 80s. Great band, but not so great for my gay identity.

You released your last record Sunshine Rock in 2019. Were you expecting to write another record so quickly?

No, not at all. I was expecting to work on the box set [Distortion: 1989–2019]. Ideas just started coming fast and furious. I was playing a lot of guitar and the political situation was getting worse and worse. I had written the song “American Crisis” back in 2018. I had that as a tentpole pole to start with. When I chose to start with that and build around it the work got really easy all of a sudden.

How do you keep up your stamina and momentum as a songwriter?

Well, with Hüsker Dü there were two principal songwriters. So, there was a lot more to work with. But, this is what I do, my life’s work. When I get the inspiration and I get the premise for a record, then it’s just doing the work. Sitting down every day and writing. It’s about being disciplined. I set goals for myself.

You mentioned the box set, Distortion: 1989–2019, of your post-Hüsker Dü solo work. Did working on the box set give you a chance to reflect on your legacy?

I’m terribly flattered that people are interested in a volume of work that’s that big, 30 years of work and all that music. Putting the box set together wasn’t difficult, but I did not foresee how the songs change ever so slightly in meaning over time. To go back chronologically, and address each record, making sure the lyrics are right, listening again for the mastering and reimagining the artwork, that brought a lot of people back to life. It brought a lot of places back into view.

I know you lived in Berlin for a while and have moved around quite a bit. Do you feel like the cities you live in affect you creatively?

It’s probably the main consideration when I look back on everything. And when I was speaking about the box set and reimagining the new album art, that was the idea, to try to highlight my personal little monuments or signifiers of the places that I lived. Environment is always key, whether it's the actual outdoor weather, the food or the pace of people.

You got into clubbing and spent some time as a DJ. How did you get into that scene?

That was one of the best parts of my life. I started making music professionally in 1979. In 1998 I put out a record called The Last Dog And Pony Show. The idea was that I was going to step away from 20 years of playing in loud rock bands and living on the road in a van. I was in New York City at the time, and was really trying to claim my gay identity. The beginning of 1999, I was pretty deep in the West Village and Chelsea scenes, in New York, and the soundtrack of the gay scene was club music. There were big DJs at the time like Paul Van Dyk, Jimmy Van M, Deep Dish, and all the big clubs like Roxy and Twilo. Gay New York at that period was really super gay and super amazing. Every day was like gay Disneyland. I threw myself into the community and started becoming a completely different person. That was my soundtrack everywhere that I went.

Now that Blue Hearts is out how do you hope it can help people at this current moment?

The initial reaction has been really strong. I felt it in January 2020 right before going into the studio, I was out playing a lot of solo shows in the northeast in America. To make the record and hear people, even before I recorded the album, say you're telling a story that we don't have the power to tell. Go tell that story, we're behind you, put a voice to all of this corruption. I was like, OK, I’ll do it. I think that because the record is good, and people are responding well it gives me these interviews to continue to give the story deeper colour and meaning. I guess this is what I get to do after 40 years of doing my work, I get to have a moment where I can say whatever I want. It's important as an artist, because I have a ‘lowercase m’ microphone to use, I should probably use it while I can and not worry about alienating parts of my fan base. If we all don’t say what we really feel now, we may not get another chance to say it.

That’s very true.

Yeah, I don't want any confusion in the future, when history is written, that I did not speak up this time. There were times in the 80s where I should have been more vocal. Those are those are nagging laments that I have and Lord knows I don't need any more of those.

Do you think it would have been possible for you to speak up in the 80s?

Of course. Tom Robinson said more, Jimmy Somerville said more. I could have said more, but I wasn't comfortable. This fascism that's upon us in America, to recognise the similarities that it carries from the 80s, I certainly cannot remain silent at all this time. I have absolutely nothing to lose by telling my truth.

Blue Hearts is released by Merge and is reviewed in The Wire 441. Distortion 1989–2019 is released by Demon and is reviewed in The Wire 443.

Leave a comment