“A man that makes use of his hands and brain”: Val Wilmer remembers a ‘Nigerian pioneer musicologist’

June 2021

When the Nigerian saxophonist Chris Ajilo died in February he was hailed at home as a legend of Nigerian music. Here Val Wilmer fills in the details of his formative experiences in the UK’s 1950s jazz clubs and dance halls

When the Nigerian saxophonist Chris Ajilo died on 20 February aged 91 it received scant attention in the UK music media. The obituaries in the Nigerian media inevitably focused on his considerable reputation in his home country – as the musician who led Nigeria’s Independence Day celebrations, and recorded the Lagos anthem “Eko O Gba Gbere”, or as the president of the Nigerian Union of Musicians, and the first head of its Performing and Mechanical Rights Society. As Ajilo himself once put it: “I am not only a musician, I am a copyright man, a Trade Unionist, a man that makes use of his hands and his brain.”

But like a number of other Nigerian musicians, Ajilo developed his musical skills in the UK, where in the early 1950s he came into contact with some of the country’s best modern jazz players, and, unusually for an African musician, worked in commercial dance bands. Many of the details of this period of his life remain little known, but my researches reveal the crucial lessons he learned while studying and working in London, Birmingham and elsewhere, as well as underlining the role played in the UK’s emerging modern jazz scene by the African and Caribbean musicians who moved to the country in the years after the Second World War.

Christopher Abiodun Ajilo was born in Oshun state on 26 December 1929. He attended grammar school in Lagos where he learned music theory, a compulsory subject at the school. In 1947 he decided to leave Nigeria. After making his way north up the coast to Dakar in Senegal disguised as a soldier, he boarded a ship bound for Britain. He arrived as a stowaway, which meant he received a short mandatory prison sentence. On his release he worked as a civilian in an army camp before moving to Birmingham. He worked in a foundry to pay for music lessons then enrolled in London’s Central School of Dance Music. There he trained as a commercial dance band musician under professional players including guitarist Ivor Mairants and saxophonist Johnny Dankworth, and began playing jazz.

Still in London he learned to repair saxophones, which brought him a small income, and took private lessons from the prominent modernist Don Rendell. But the early 1950s fashion for Afro-Cuban bands meant he was more in demand as a percussionist than for playing jazz on the saxophone. He worked with Kenny Graham’s pioneering Afro-Cubists, when its line-up also featured Nigerian conga player Bob Caxton, as well as a group led by the celebrated Nigerian percussionist Ginger Johnson, and jammed with Jamaican musicians trumpeter Dizzy Reece and saxophonist Sammy Walker at after hours sessions.

In spite of all this activity, due to personal commitments he moved back to Birmingham, where he met a group of aspiring Nigerian instrumentalists with whom he formed his first group proper, The Coot Cats Of Africa. He then moved to Manchester where he did factory work and played at the Mayfair, a celebrated after hours club, in the company of the Anglo-Nigerian saxophonist Syd Archer.

He returned to London and began playing at both jazz clubs and dance halls leading his own Afro-Cubists. There was a limited pool of black musicians working in London in the early 1950s, so most of the group members were white, but through these contacts he got the chance to join a stable dance band for a whole summer season. Working at the Nottingham Astoria with Arthur Rowberry’s band not only guaranteed he had steady work for a time but also gave him the opportunity to concentrate on the saxophone and practice and hone his formal skills. He would later write in his autobiography, Reminiscences Of A Nigerian Pioneer Musicologist, that he learned more from working with professional dance band musicians than any amount of academic study.

During this period he would return to Birmingham to play tenor with his own Cool Cats, before again moving to London. In October 1954 he took a new group on tour, his All-Coloured Afro Orchestra, and this time all the musicians in the group originated from the Caribbean or West Africa. The group played jazz clubs in West London and travelled to Europe, before Ajilo joined the group led by the Ghanaian-descended British singer and pianist Cab Quaye, still on saxophone. He continued to work as a percussionist, including with Quaye’s Sextetto Africana, another all black group, playing clavés on their recording of “Everything Is Go”, a calypso about the US fighter pilot, and later astronaut, John Glenn. With the Ghanaian saxophonist Sammy Lartey, Ajilo formed his Afrochestra to play late night sessions at the Latin Quarter in Soho, and received a positive review in Jazz Journal.

Fired up by these experiences, Ajilo returned to Nigeria in 1955 with a mission to introduce bebop to the country. With Lartey in Lagos he formed The Ajilo Jazz Club which also included tenor saxophonist Bobby Benson, but when the project foundered, he returned to playing highlife, then the dominant popular music throughout West Africa, with his group The Cubanos: tracks by the group from this period were included on the 2009 Honest Jon’s compilation Marvellous Boy, and the 2015 Soundway anthology Highlife On The Move.

Work with The NBC Dance Orchestra and dance bands that had residencies at a number of major Lagos hotels followed, but the desire to play jazz was strong. In the early 1960s he was a member of The Koriko (Wolf) Klan with pianist Wole Bucknor and drummer Bayo Martins, an adventurous forerunner of Fela Kuti’s first jazz group. His musician associates at this time included trumpeters Mike Falana and Zeal Onyia and pianist Art Alade, all players touched by jazz, while he continued to pay the rent working with The NBC Orchestra under the direction of composer Fela Sowande.

In 1960 Ajilo took over from Bobby Benson as the President of the Nigerian Union of Musicians. That same year he led the orchestra that performed at Lagos’s Federal Palace Hotel for Nigeria’s official Independence Day celebrations. “The celebration committee wanted to bring in bands from Europe,” he later explained. “The union refused and insisted we didn’t need a foreign band to play on our Independence Day. We formed a national band and rehearsed for almost six months. The celebration was a thrilling experience.”

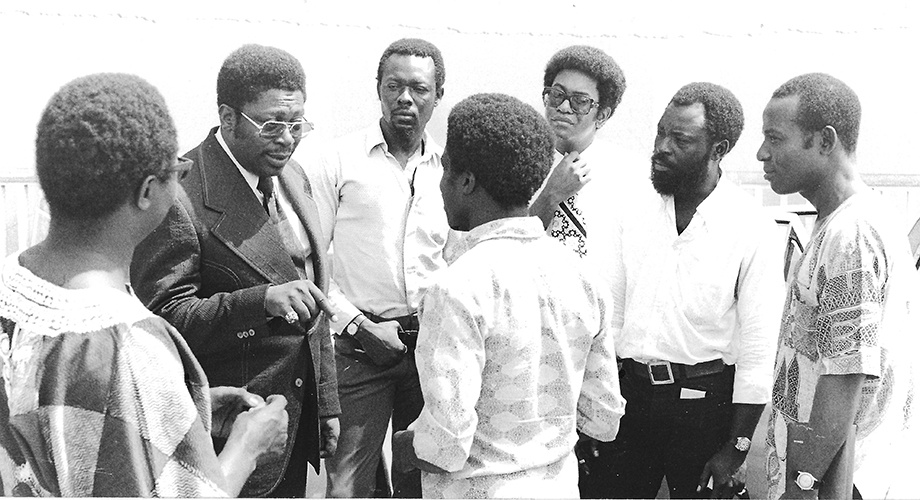

In the early 1970s his concern with raising the status of professional musicians in Nigeria led to his involvement with the Musicians Foundation, an organisation spearheaded by Bayo Martins. I met Ajilo in Lagos in 1973 when the foundation was involved with a tour by BB King, and was surprised to discover that he was familiar with my writings on jazz and clearly relished the time he spent in the UK learning his craft.

BB King meets his Nigerian hosts, including Chris Ajilo (far right), Lagos 1973. Photo: Val Wilmer

For three years Ajilo led The Jazz Preachers who performed on Art Alade’s popular TV show, and in 1977 he performed at FESTAC, Nigeria’s prestigious international festival. In Ibadan he taught for eight years at the University’s International School and played flute and clarinet in several operatic productions. As the first head of Nigeria’s Performing and Mechanical Rights Society he helped secure royalties for the country’s musicians. Through the 70s and 80s he worked as an in house producer at Polygram, producing more than 50 albums, including ones by Victor Olaiya and Chief Osita Osadebe. He remained involved with music promotion but worked increasingly outside the industry. When he retired to his village in Oshun state in 2007 he was primarily occupied with the church. But in 2017 his song “Eko O Gba Gbere”, which he’d first recorded in the early 60s with The Cubanos, was declared the official anthem of Lagos state during its 50th anniversary celebrations.

In the 1990s I wrote to Ajilo when I was trying to discover the fate of Mike Falana (who I wrote about in The Wire 424). I received a helpful and informative reply, and so when the film maker Alex Emanuel was headed for Lagos three years ago I directed him towards Ajilo to help shed some light on the history of modern Nigerian music. Emanuel found Ajilo living in Ijebu-Jesa in Oshun state, a friendly veteran who sent me a signed copy of his Reminiscences Of A Nigerian Pioneer Musicologist. It is a fascinating and thoughtful read.

Chris Ajilo, Nigerian musician and activist, 26 December 1929–20 February 2021. Subscribers can read Val Wilmer’s article on Mike Falana via The Wire’s online archive.

Leave a comment