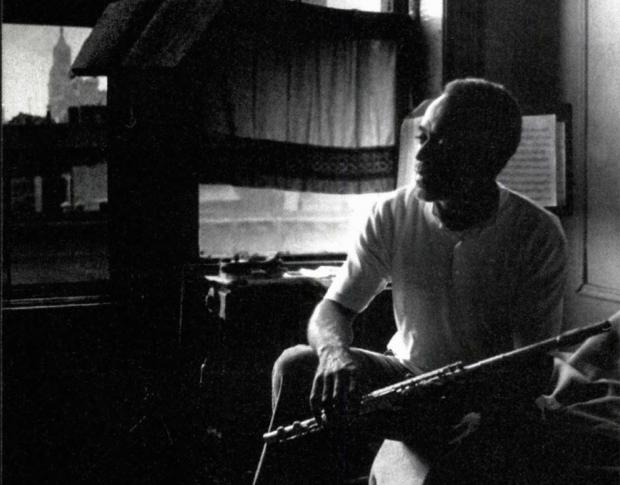

Giuseppi Logan 1935–2020

April 2020

The pioneering 1960s free jazz saxophonist learnt the high cost of freedom playing for change in New York's subways and parks before his late period rediscovery by William Parker, Cooper-Moore, and others. By Pierre Crépon

Jazz alto saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist and composer Giuseppi Logan died on 17 April 2020 at the Lawrence Nursing Care Center in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York. He was 84. The cause was related to Covid-19, collaborator Matt Lavelle told New Jersey based radio station WBGO.

“For those not familiar with the term new music, it refers to the kind of music first put forward by Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. It is now being played around New York, especially in the East Village… Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Paul Bley, Roswell Rudd, Le Sun Ra, Burton Greene and Giuseppi Logan are just a few of the better known leaders playing this music,” saxophonist Frank Smith wrote in East Village Other in December 1965, encapsulating Logan’s peer group.

Moving to a description of a recent Slugs' in the Far East club appearance, Smith added “the music was very powerful and beautiful with Logan playing things so piercingly sad that he almost had me in tears. His strongest quality seems to be his soul-wrenching sadness mixed always with a touch of tenderness.” Logan’s piercing tone was distinctively his own – perhaps a jazz saxophonist’s most important achievement – and he was able to organise an equally distinct world of sounds around it.

Joseph ‘Giuseppi’ Logan was born on May 22 1935 in Philadelphia. His family soon moved to Norfolk, Virginia. His mother was a homemaker and his father a firefighter, who played spirituals on the family’s old piano. It became Logan’s first instrument, on which he learned boogie woogie. In school, he played drums and took up the alto saxophone. Teenage playing experiences included work with saxophonist Earl Bostic.

Logan married, and he studied briefly at Combs College of Music in Philadelphia. He then learned theory at the New England Conservatory in Boston. At the city’s 1960s jazz spots, opportunities arose to sit in with Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Eric Dolphy and Sonny Stitt. At a 1963 jam session, he met drummer Milford Graves, who recalled Logan already carried an abstract player reputation and expressed himself in the style he would become known for.

Logan moved to New York in 1964, integrating the Village avant garde and meeting musicians such as Albert Ayler, Marion Brown and John Tchicai. Logan played with pianist Paul Bley, trumpeter Dewey Johnson and drummer Rashied Ali, among others. As the regular alto in trumpeter Bill Dixon’s ensembles, he played the historic October Revolution in Jazz festival, also appearing there as a leader.

Two days later in October 1964, Logan led his first recording session, for the recently created ESP-Disk' label. The resulting The Giuseppi Logan Quartet, featuring a line-up of Graves, pianist Don Pullen and bassist Eddie Gomez playing Logan originals penned for the session, is widely considered a free jazz classic, its use of odd meters and non-Western instrumentation preceding their common acceptance.

Writer Amiri Baraka famously described in his autobiography the moment he decided to abandon his bohemian Village life, on learning of Malcolm X’s assassination while attending a bookstore event in February 1965. This literary party was select enough to garner New York Times coverage, illustrated by a picture of Logan’s group, who was providing the music. Logan was an early participant in Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in Harlem while remaining part of the downtown loft scene, notably with pianist Dave Burrell, drummer Bobby Kapp and bassist Sirone.

On May Day 1965, he recorded part of his second ESP LP More at a Town Hall concert also featuring Bud Powell, Byron Allen and Albert Ayler, whose segment became Bells. More included further demonstrations of Logan’s multi-instrumentalist skills, on flute, bass clarinet and an extended solo piano piece. But a third ESP album, The Giuseppi Logan Chamber Ensemble In Concert recorded with four classical musicians, remains unreleased.

In the Spring of 1966, Logan’s quartet backed singer Patty Waters on dates documented on College Tour. In July, Logan was a sideman on trombonist Roswell Rudd’s Everywhere, which featured Logan’s “Dance Of Satan”. Soon after, an ambitious series of avant garde jazz presentations took place at New York’s Village Gate. Coleman, Coltrane and Shepp headlined. Logan, Brown and Ayler came in second.

Logan’s New York scene presence then dimmed. He could still be heard playing Slugs' Saloon matinees in 1968, but did not follow suit when many colleagues made the transition to Paris. By the early 1970s, word was circulating that Logan had become a postal service worker. The jazz world moved on.

“I was walking on 57th Street the other day and I saw a saxophone player playing in the rain, in the street, and it was Giuseppi Logan,” saxophonist Jackie McLean said in a 1979 Musician, Player And Listener interview. “Giuseppi has made a contribution to this music… Giuseppi’s out there and it’s a shame.” Around this time began a period during which Logan alternated between years-long stretches in mental institutions and homelessness in Virginia, experiencing total loss. Logan said his institutionalisations were drug-related and he underwent treatment with Thorazine, an antipsychotic.

Two full music-less decades resulted. “They shook all that out of me,” Logan told writer Jason Weiss in Always In Trouble: An Oral History Of ESP-Disk’, The Most Outrageous Record Label In America. Eventually he was able to buy a saxophone at a pawnshop and started to play again.

Giuseppi Logan modelling threads for Assembly New York's 2009 winter collection. Photo by Margo Ducharme

By 2008, he had returned to New York. He slept in shelters and played in the subway, at the 34th Street-Herald Square station and then at Tompkins Square Park in the East Village. “I’m disillusioned with America,” said Logan in a 1966 short film shot at that exact location. Gentrified New York had not turned into a more welcoming environment and he had become a local figure playing standards for change in the park.

Logan met trumpeter and clarinettist Matt Lavelle, who became a major supporter of his comeback attempt. After appearances with bassist William Parker and in trombonist Steve Swell’s big band, the first gig under Logan’s name took place at the Bowery Poetry Club in February 2009, with a group assembled by Lavelle. Logan guested with bassist Henry Grimes at that year’s Vision Festival. Through the Jazz Foundation of America, he obtained a small room, and more than two dozen appearances with Lavelle followed, centred on standards.

Attempts to interest jazz labels in a new recording were unsuccessful. The Giuseppi Logan Quintet, a session with Lavelle, Burrell, bassist François Grillot and drummer Warren Smith, was ultimately released by Tompkins Square Records in 2010. The pressing of another session featuring pianist Cooper-Moore, The Giuseppi Logan Project, was crowdfunded by guitarist Ed Pettersen in 2012, a New York Times feature on Logan boosting the project.

An ESP studio session that was to feature new music and Logan's son Jaee Logan on piano was cancelled in 2013. A broken hip got in the way of further efforts. Logan’s last released session …And They Were Cool took place in June 2012 and was released by the Parisian label Improvising Beings. Its sleevenotes conclude with “free jazz has become the story of a music sadly turning its back, and rather doggedly, to the visionaries who taught us freedom”.

Logan had married twice. He is survived by two sisters, eleven children, and several grandchildren. Another child preceded him in death.

Comments

What a loss of such an original voice.

Iain Patterson

Doing Covid 19 isolation. Pulled Roswell Rudds EVERYWHERE . Haven't listened to it for years. Heard Giuseppe, googled him and found this article. RIP Giuseppe Logan. A pioneer indeed.

Ronspin

Leave a comment