Essay

Process of Time

January 2026

To make sense of ongoing tech revolutions, a new generation of musicians is making music that metabolises electronic processes through analogue forms, argues Ryan Meehan

To make sense of ongoing tech revolutions, a new generation of musicians is making music that metabolises electronic processes through analogue forms, argues Ryan Meehan

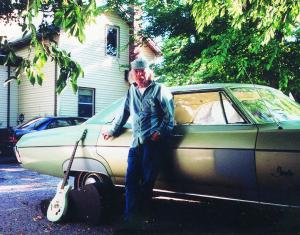

Following Michael Hurley’s death on 1 April, Ryan Meehan tracks the outsider folk singer and cartoonist’s journeys across America and remembers the restless bohemian spirit that powered them