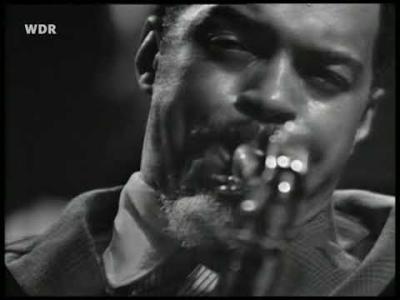

David Grundy watches recently unearthed footage of saxophonist Albert Ayler in concert from 1966

For years, it was almost impossible to see footage of Albert Ayler. Infamously, a performance filmed for the BBC’S Jazz 625 was wiped in an archival cull. A concert film of Ayler’s Foundation Maeght performances, Le Dernier Concert, remains unreleased. Beyond tantalising snippets in Kaspar Collins’ film My Name is Albert Ayler, and online fragments from Ayler’s final Foundation Maeght performances, that was it.

In late 2024, however, musician Jay Korber uploaded some astonishing new videos to his YouTube channel. There are three performances: six minutes from the Sigma Festival in Bordeaux, ten minutes from the SWF TV studios in Munich, and a full 30 minute set from the Berlin Jazztage, all filmed on a 1966 European tour featuring Donald Ayler on trumpet, violinist Michael Samson, bassist Bill Folwell and drummer Beaver Harris.

As Peter Niklaus Wilson notes in the recently translated biography Spirits Rejoice: Albert Ayler And His Message, Ayler had been touring Europe as part of a package tour organised by impresario George Wein, supporting the star turns of Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, Max Roach and Dave Brubeck.

Michael Samson recalls ecstatic responses on some of the gigs from the tour, comparing their reception in the Netherlands and France to that of The Beatles. Yet in the West German gigs, the be-suited audience appear indifferent, if not hostile.

European critics often misunderstood Ayler’s music as a kind of nihilistic dadaism. What both critics and audience missed was its appeal to unity. Ayler’s new music was designed precisely to reach out, to create a collective experience whose call the audience seem to have been unable to hear. Wilson describes the period 1965 to 1968 as the transition from free jazz to what Ayler called “universal music”, with melodies no longer merely a ‘catapult’ for free improvisation, but the main substance of the music. With solos reduced to short interludes, Ayler’s band offers a continuous stream of cadential, decorated, ornamented, amplified, reiterated, singing declaration, with distant parallels to the melody focused, suite-like structures being explored at the same time by Ayler’s former collaborator Don Cherry.

Ayler himself described this process as “trying to get more form in the free form... something... that people can hum... I want to play songs like I used to sing when I was really small. Folk melodies that all the people would understand.”

Samson suggests that those melodies drew from Ayler’s past in the Baptist church, where communal participation through singing had a pride of place. (They also echo marching band music, folk songs, and the nursery rhymes he’d heard as a child). These new, extended songs were an attempt to create ‘spiritual unity’, to bridge the performer/audience divide in a collective experience.

This wasn’t a rejection of free playing, but its dialectical outgrowth. In free jazz, tonality is not so much denied as sublated and fulfilled: all the keys, sounding at once. As his free music had drawn out the noise inside the melody, Ayler’s universal music drew out the melody inside the noise. Offering nearly continuous micro-improvised commentary on melodies that function, not as the heads that preface discrete solos, but the substance of the music itself, Ayler and his comrades at once refuse separation and make it the music’s dialectical basis. Noise is an extension of melody; melody contains within itself the sound of noise.

Though Ayler himself used the term ‘folk’ to describe the music – his most famous song “Ghosts” was, according to the Ayler scholar Richard Koloda, based on the Swedish folk song “Torparvisan” – his was not the romantic anti-capitalism of the folk revival, with its invocation of an idealised past. Rather, it’s shaped by the experience of modernity. Like jazz itself, his music is syncretic, drawing in all the ear can hear, resisting all labels imposed on the music, such as ‘jazz’, ‘free’ or otherwise. In this, and without ever losing sight of particularity, it opens up onto an as yet realised universalism.

“Ghosts”, Don Cherry said, “should become mankind’s national anthem!” Nation within a nation, internationale, outernationale. This new footage provides valuable evidence of this music’s living appeal.

The Wire has published many articles on Albert Ayler. Subscribers to the magazine can search, browse and read them all in the online library.